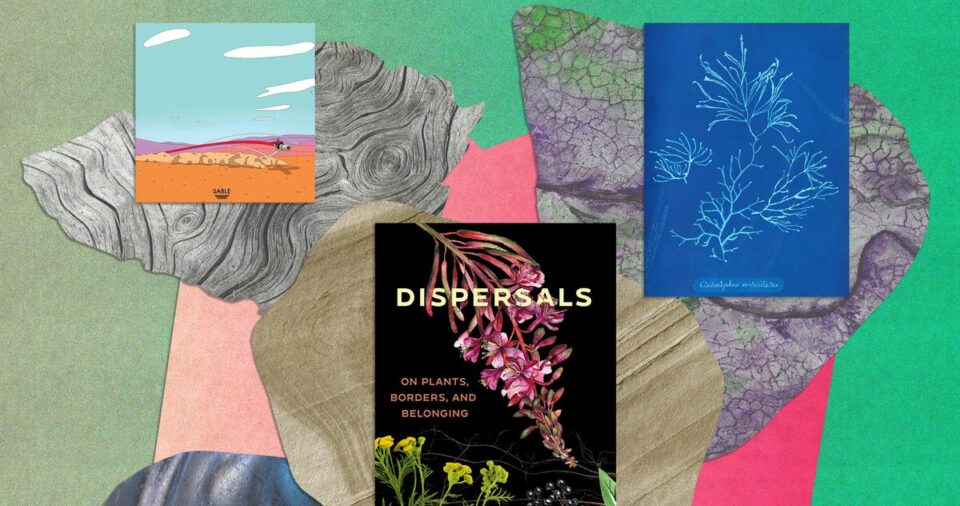

Jessica J. Lee has a favorite weed. Known in the U.K. as rosebay willowherb and in North America as fireweed, it’s a lusciously leafy green stalk topped with a cone of delicate pink blooms. It envelops long-abandoned grounds and the cover of Lee’s latest book, Dispersals, a collection of 14 essays about migrations both human and botanical, and the ways that imperialism and colonialism have formed their paths.

Lee’s lyrical prose sprouts from a fertile ground of intensive research and intimate memories — memories that are by turns sharply vivid and pleasantly hazy with the distance of time. She wrote the book primarily during her pregnancy and in the early months of motherhood, an experience she says unstitched her ideas about autonomy, community, and what writing work could look like. “I wrote huge amounts of it just text messaging myself on my phone while she napped on me in a dark room, breastfeeding,” says Lee. “I was writing in these tiny gaps, in these tiny fragments, and that was okay. I was really raw, and I was in a moment of deep tenderness with my baby. I needed to treat the writing process with that same kind of care.”

There are other ways Dispersals marks a bit of a departure for Lee; her first two books go deep on one subject, but here, she moves seamlessly from seaweed to soybeans to citrus. Lee is not only a nature writer, but an environmental historian with a Ph.D. in environmental history and aesthetics who brings together scientific knowledge and personal experience. “I’m not very good at separating them out, which is probably why they all come together on the page,” she says. “As I get more comfortable with my own voice as a writer, it’s often about letting go of the pressure to write in this objective voice from above. Aren’t we subjective and emotional creatures? And isn’t our science also that? Isn’t so much of our culture that? What if we just took that as the starting point?”

Below, Lee shares five of the cultural touchstones that helped her write Dispersals.

Small Bodies of Water by Nina Mingya Powles

This book was, for me, the prototype of how to put together an essay collection. It’s dreamy, and it refuses the idea of home as being a single place. This was one of the texts I studied a lot when I was thinking about how I wanted this book to be shaped. I often think about writing as something we do in community, in response to one another and to other artists and writers. I kept rereading Nina Mingya Powles’s Small Bodies of Water.

In one of the essays, I wrote about making soy sauce. We let jars of sauce age for a year, and I think I ended up opening them and processing them just in the last week of my pregnancy before my daughter was born. It was all very strange — a lot of things coming into fruition at that moment in my life. I had a huge belly, and these jars were as big as my belly. Most of the soy sauce that I made that I couldn’t finish I gave to Nina, who lives in London, along with most of my plants, and she then wrote about cooking with my soy sauce. I love those little nests of things that happen within our community.

Gathering Moss by Robin Wall Kimmerer

Everyone always talks about Braiding Sweetgrass, but I’ve always been a Gathering Moss girl. I really recommend it. Before I had ever written a book, or realized I was going to be a writer, I remember thinking to myself, One day I would love to write a cultural history of mosses. I Googled to see if anyone had done that, and of course Robin Wall Kimmerer had. I asked a question and she answered it. It’s such a beautiful one.

But coming back to this idea of decolonizing and unpacking that patriarchal voice of what science and science writing looks like, this book was such a great example for me because it’s this personal memoir of a scientist in the field. It’s mosses as these intimate things that she works with daily and encounters. She modulates between that very intimate, personal voice of her daily life and the work she’s doing out in the field cataloguing mosses so seamlessly that it drives home this understanding that we’re not just subjective beings in one part of our lives and objective in others. It doesn’t work that way; we bring our whole selves to everything we do.

Soft Sounds From Another Planet and Sable (Original Video Game Soundtrack) by Japanese Breakfast

Historically, I do pick one text to listen to as I write a book. That’s how I’ve always worked. Each of my books has had one song or one playlist that I’ve listened to on repeat. Around the time I was writing, especially when we were in Cambridge, I was listening to a lot of Japanese Breakfast. I’d been listening to Japanese Breakfast for years, but somewhere around that time my husband also caught on, so he would play them in the house or in the car. My husband’s a big gamer, and he got Sable, and then he was like, “Jessica, Jessica, Japanese Breakfast did the soundtrack for this video game.” The kinds of songs that have this yearning that feels like momentum forward help me in my writing. You can physically get caught up in the movement of the song. “Glider,” the song from the Sable soundtrack by Japanese Breakfast, really did that for me.

But I also struggled with this book, because I had just had a baby and I could barely listen to anything. You could also say the white-noise machine that I would put on when my baby slept was the soundtrack for this book. I was in a dark room with this white-noise machine on, holding my baby. Usually she was on my boob. I maybe had one hand to type something on my phone. The writing was slower. I labored over sentences in ways that I hadn’t before. This book feels very lyrical in places, and I can tell all the lyrical parts were written in those moments where I was just writing a line or writing two lines. All of the more scholarly sections were written when my husband would take the baby and I would be like, “Okay, I’m at my desk. I’ve got my sources and 30 minutes and Japanese Breakfast. Let’s go.” I can tell the difference when I read it back.

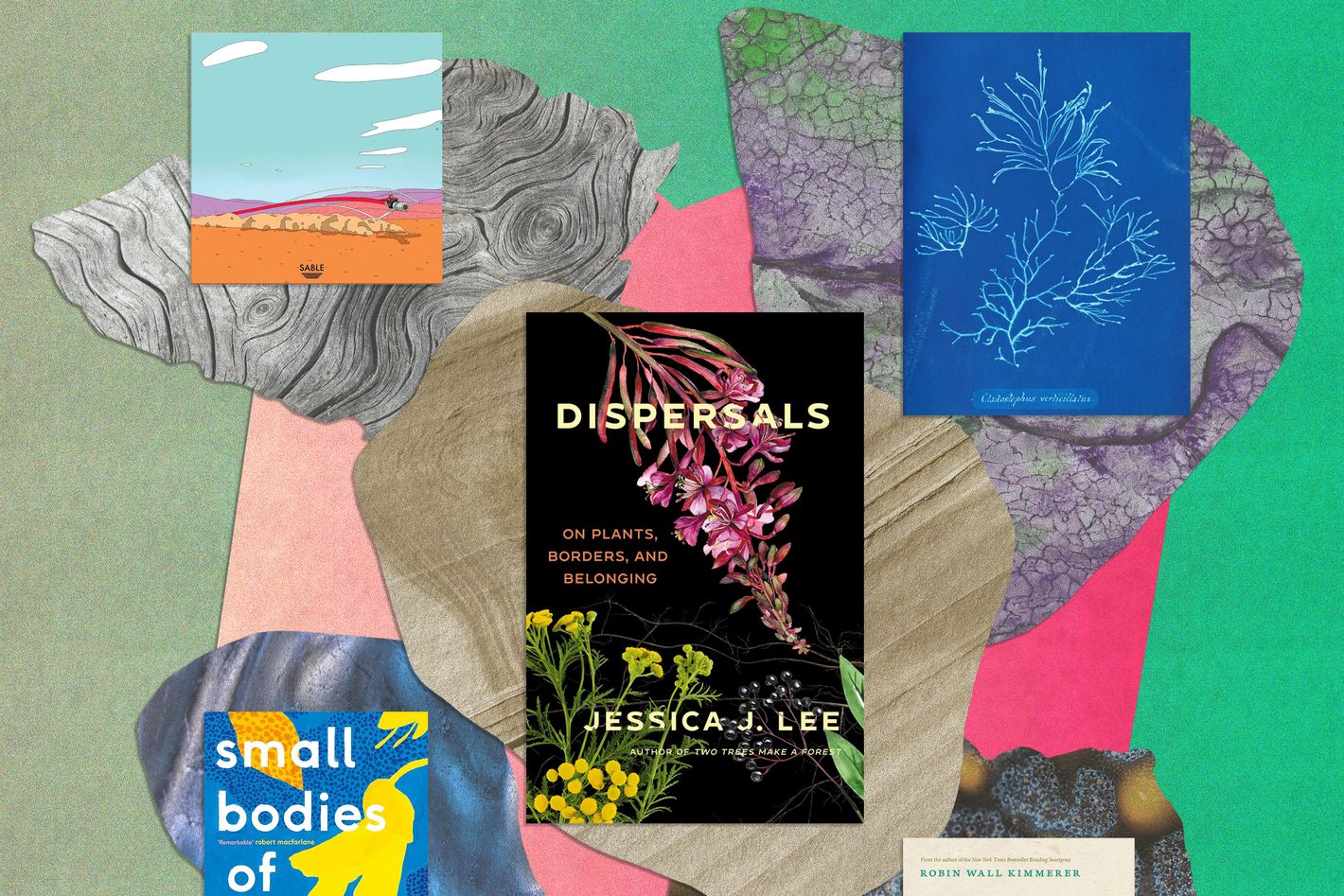

Anna Atkins’s Seaweed Cyanotypes

Anna Atkins did a huge number of cyanotypes of British seaweeds in the 19th century. I came across them during my studies originally during my Ph.D., and then I came across them again and was reminded of them through this photo gallery that The Guardian put together a few years ago of some of her work. I love cyanotypes as a form; the minimalism of stark blue and white. But once I’d actually learned about Anna Atkins’s work, it was so much more remarkable to me. She did the first photographically illustrated book of all time. She’s a real pioneer. And her images capture that strange dreaminess of the ocean and the delicacy of seaweeds for me.

Kamikaze, Cherry Blossoms, and Nationalismsby Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney

This book helped me process the idea of nature mobilized as a symbol and the political and social implications of that. I had a similar experience while writing my second book with a book by Emma Tang called Taiwan’s Imagined Geography. That book became a really scholarly treatment that helped me think about what it was I was trying to say in that book, and for Dispersals, Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney’s book on cherry blossoms helped me pinpoint what I was trying to say about cherry blossoms. I’m really indebted to her research, because it’s so thorough and absolutely fascinating on this idea of these symbols not being neutral in the way that we deploy them and that they get deployed to really dangerous ends.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

More From This Series

- Witnessing Brutality

- Walela Nehanda’s Debut Memoir Rejects Expectations

Katja Vujić , 2024-04-15 20:26:49

Source link