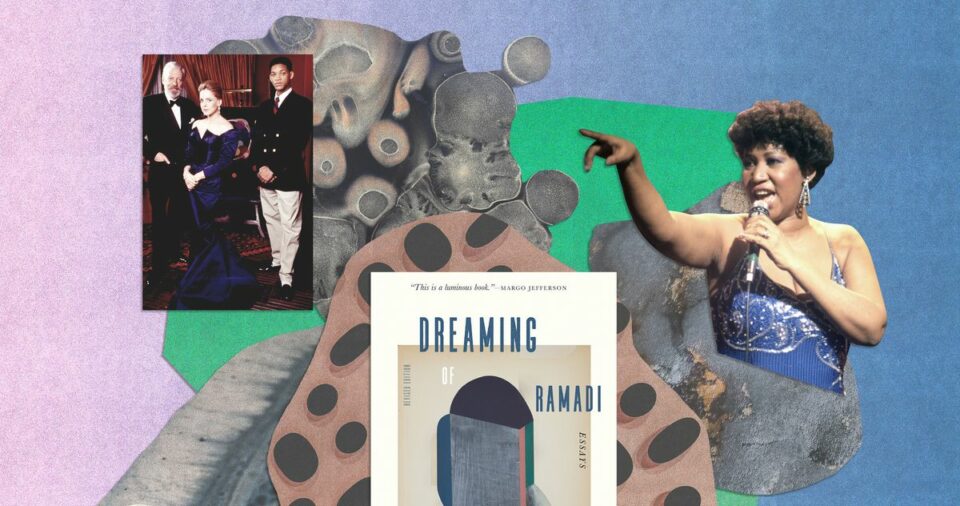

Aisha Sabatini Sloan’s essay collection Dreaming of Ramadi in Detroit has never felt more relevant. Part of the book’s timelessness can be explained by its wide-ranging references, which oscillate between mediums — from the paintings of Richard Diebenkorn to the ABCs of opera to the occasional Will Smith movie. The questions around the societal ills confronted in the book are ever-present, but Sabatini Sloan’s essays never lean on easy answers.

Sabatini Sloan’s writing is spacious and straightforward, made up of concise, poetic sentences that leave plenty of room for the many questions and minimal answers she puts forward. Since writing the original version of the book, which was published by a micropress in 2017 before being expanded to include updated pieces in 2024, she has been transformed many times over. “I do feel a little unfamiliar to myself,” Sabatini Sloan admits, “but that’s also the fun of it: Re-inhabiting, or just realizing that that ‘myself’ is a collection of different people, and there’s a fondness for going back to that person.” The seed for what eventually became Dreaming of Ramadi in Detroit was planted while she was living in Tucson, taking meditation classes regularly, as one does in Tucson. One class in particular left an outsize impact: a meditation on death. “We had to do a corpse meditation, which in this case was imagining loved ones ill, dying, and dead. It was such a profound experience. And it made me interested to meditate on loss with people.” The second essay in the book, “Ocean Park #6,” does just that, pulling in stories and insights from a close family friend who’d lost her son, a surfer, to cancer amid the oceanic imagery of Richard Diebenkorn’s paintings.

Even as the book itself progresses, so does the perspective of the person writing it. Sabatini Sloan’s relationship to policing, for example, evolves in a major way. In one essay, she visits Detroit, where her family comes from, and is invited to ride along with her cousin, who is a cop. She grapples with her cousin’s position in the community and, by extension, her own. But she is more afraid of the violence she and her cousin might face than the violence they or the institution they represent might enact. By the time she arrives at the titular essay, “Dreaming of Ramadi in Detroit,” she feels differently. She has grieved Michael Brown and Eric Garner and many others, and her new fear is of the officers. “My cousin is my cousin,” she writes. “She’s my blood. But so am I Black. My father is Black. She’s white. But her children are Black. Our affiliations are bleeding all over the place.” Her family contains a police officer, and it also contains members who are or have been incarcerated.

The writer is as transformed by the violence she sees up close as she is by the violence happening further away from her, whether across town in Detroit or overseas in Palestine. Through her relationships to her family, she’s inhabited several perspectives, borne of her own experiences and the experiences of those closest to her. “We can’t quiet the fact of violence,” says Sabatini Sloan. “It erupts in your dreams; it comes through in your mood, in the effort of moving through your day. I think a lot about how grief hides inside of us, and the responsibility we have to sit inside of it and let it take over.”

Midnights by Jane Miller

One of the most instrumental things for me was working with poets in grad school. I took this great craft class with the poet Jane Miller, and she was writing this book of prose poems called Midnights at the time. Her relationship to writing something that was closer, for her, to nonfiction just illuminated something for me about writing through the present moment, and letting the way that you encapsulate past, present, and ideas of the future be a way of crystallizing what’s true in this moment, as opposed to what’s always going to be true. It was a kind of poetic logic that allowed me to write essays in a way that I felt like I couldn’t before, because I felt like I was lying. Poets really allowed me to conceptualize what an essay can do in a way that made me feel like I don’t have to pretend to know things.

Six Degrees of Separation, directed by Fred Schepisi

I was just talking with someone today about how you can’t ignore the little things in yourself that are trying to get your attention. I was not sure, when I was asked to write “That Black Abundance,” how I was going to do it. But I kept thinking about that movie. Watching it really did help me navigate what it was that I was trying to think about. I can’t remember when I first watched it, but the setup is everything I love about an essay. You’ve got your complicated art environment, you’ve got your paintings, you’ve got race, you’ve got performance of race and performance of class. And then also the element that I’m only now realizing I’m really curious about, which is the poetics of dialogue, the playwriting vibe. It’s such a theatrical film, in the sense of the dialogue being so studied and careful — that playwright’s touch.

Heavy: an American Memoir by Kiese Laymon

It feels really relevant to me that Heavy is now a part of this book. It wasn’t originally; it’s one of the later additions. Kiese Laymon has been my teacher over the last ten years. The first essay of his that I read was in 2013, and then I went on to teach his first essay collection the following year. And then I ended up teaching Heavy. His work makes teaching feel electric and magical. He zoomed into my class the first time I taught his work, and it was parents’ weekend, and he just brought so much grace into that room. It really transformed us as a class after that. I think it’s his honesty and his rigor within the space of a sentence. When I taught Heavy, moving through that book together called for a kind of honesty that I think we were all really grateful to be asked to engage in with ourselves and with each other. It made the work of being in a writing classroom so much more productive and interesting. I’ve learned a lot about myself through the things that he’s made me have to think about, in my identity and my growth as a person in the world. He’s one of those people that I’ve never studied with officially, but he’s absolutely one of my biggest teachers.

“Nessun Dorma” performed by Aretha Franklin

I’m not an opera aficionado, but it’s twofold. The “Flower Duet” is the song that I listened to a lot while writing “D is for the Dance of the Hours.” I think that I referenced in the beginning, driving across the country with my dad and listening to the “Flower Duet” over and over again, it’s his relationship to opera. The more distance I have from it, the more I feel like that essay is about him. It was listening to the “Flower Duet” that created an entry point for thinking about opera and Detroit. But also, his journey as an artist in the world in many ways started at the time that he played a bit part in Aida.

Aretha Franklin singing “Nessun Dorma” is another pivotal hinge for the essay. Part of the meaning of my dad’s repeated listening to that song is that it’s sort of a Moonlight moment of like, “Actually, Pavarotti is not going to sing this. Aretha Franklin is going to sing this.” A Black woman just annihilating this operatic song feels like what the essay is thinking through — a Black city that is as operatic as they come. That was one of the YouTube videos that he kept playing around the time that I wrote that essay. And he still does; that’s a performance that gets him choked up. But also, my mom is Italian. We listened to Pavarotti a lot growing up, and the idea of Aretha Franklin singing a Pavarotti song has significance in terms of my family’s relationship to itself, of these cultures being in conversation with each other.

City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles by Mike Davis

My essay “A Clear Presence” is the other heart of the collection. I originally wrote this really sprawling essay about Los Angeles for Terrain magazine that was rooted in the way that reading City of Quartz really electrified me; it was a really pivotal reading experience. The way that constellated Los Angeles as a cultural, political landscape — hellscape — with art and politics. I had originally written that essay before Rodney King died. There’s something about the way he laid everything out that set the stage for me to put those things in conversation with each other — David Hockney and Rodney King — and then when he passed away, the other iteration of the essay became clear. I don’t think I would have gotten there without Mike Davis. City of Quartz was a very instrumental part of moving toward that essay.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

More From This Series

- Walela Nehanda’s Debut Memoir Rejects Expectations

Katja Vujić , 2024-03-13 13:00:38

Source link