The hiking paths at Thorn Creek Woods Nature Preserve are rife with vestiges of the people who care about the place.

Wooden causeways protect marshy areas from hikers’ boots while protecting boots from marshy mud. Simple benches provide places to rest or contemplate the scenic forest understory. Bridges offer safe crossing spots over the preserve’s namesake waterway.

Some of the wooden improvements are adorned with plaques celebrating the Eagle Scout work that went into their construction, or reminders of the devotion of departed volunteers.

But one of the most striking installations in a landscape ostensibly shaped by ice age glaciation becomes evident at the far end of the preserve’s trail system. There, a short, quarter-mile path has been dubbed the pine tunnel. The straight trail leading to a glacial pothole lake is lined by evergreen trees situated with symmetry that harkens to the property’s previous incarnation as an idyllic picnic spot for factory workers and their families.

Arthur Mall, a native of Hammond, Indiana, who established a successful tool company in Milwaukee in the 1920s before moving Mall Tool to a South Side plant along South Chicago Avenue at 77th Street, had aspirations for a more serene operation.

He started buying up old wood lots in the 1940s at the far end of Western Avenue west of Crete as the success of his pneumatic power tool company grew amid the demands of World War II.

According to a snippet from a 1952 Tribune story collected by presumed relative Jane Mall and posted online by the Monee Historical Society, Mall bought the land not only for a larger plant at 25000 Western Ave., but the surrounding acreage as well. His plan, the story said, was to create a model community of homesteaders by placing plots in trust to be distributed to 50 employees who’d been called away by war.

The employees had a different idea. They opted for cash payouts instead of the land, and Mall decided do the homesteading himself — on an industrial scale. He hired farmers to raise livestock for meat and dairy production on some of the land, and established an airport on the far south end of his property, where the cross hatched landing strips left scars still evident in modern satellite views.

But the best, most scenic parts of the acreage were turned into a private retreat. There was a “picnic grove,” where hundreds of his employees could gather for events, and “more than 40,000 evergreen trees have been planted in a carefully planned landscaping scheme,” the 1952 story stated. Some of those were planted to outline the name “MALL” on a hillside a bit west of the factory.

Further plans included stocking the woods with game and building a hunting lodge. “Eventually the area may be opened to the public,” the story indicated.

Mall’s dream was short-lived. Mall Tool was sold to Remington Arms in 1956, along with the plant in what was by then known as Park Forest. Though it still produced power tools at the site, the gun company dissolved the Mall Tool name in 1958. Arthur Mall was a millionaire after the company’s sale, lived on Vardon Lane in Flossmoor and started a smaller company, Crete Equipment Co. He died in 1959 at Ingalls Memorial Hospital in Harvey at age 64.

Despite Remington’s firearms heritage, the company didn’t share Mall’s hunting lodge vision for the land south of Park Forest, and the acreage was sold off. Among the largest buyers was Nathan Manilow, who’d played a crucial part in developing Park Forest as a model postwar community.

Manilow, his son Lewis Manilow and powerful investors including Illinois Central Industries and United States Gypsum had a plan in 1970 to “bring a dead subdivision back to life” as Park Forest South, according to Lewis Manilow’s 2017 obituary.

Residents near the dead subdivision begged to differ. They liked the woods and little lakes along Thorn Creek and enjoyed walking the old wagon trails linking wood lots where Monee Township farmers had long harvested lumber by hand.

The woods themselves were far older than that, part of the historic Thorn Grove that showed up on surveyor maps from the 1800s, along with other notable timber stands poking from the northern Illinois prairie, like Downers Grove and Bachelor’s Grove.

A group of neighbors met in 1969 in a backyard along Stunkel Road to figure out what to do. They dubbed themselves the Walnut Hill Gang and vowed to fight the development. It proved to be a popular idea.

“The story goes that a woman named Marian Pike was a woods walker and very interested in rabble rousing,” said Judy Dolan Mendelson, a Park Forest hall of fame member who has been putting together the Friends of Thorn Creek Woods newsletter for decades.

“She got the local people to become interested in taking care of these trees that were right behind their houses, and find out just what is this Manilow development.

“They met in someone’s backyard and talked about how much should be saved, and Marian, who had walked it and studied it, said ‘All of it!’ That started them off.”

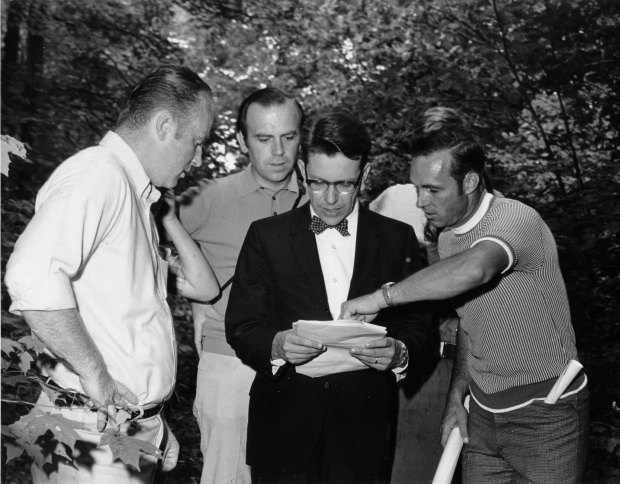

The effort grew into the Thorn Creek Preservation Association, and members recruited some allies powerful in their own right, including then Lt. Gov. Paul Simon and attorney Victor Yannacone, a founder of the Environmental Defense Fund who was instrumental in getting the pesticide DDT banned.

The Thorn Creek Preservation Association asked Yannacone at a meeting, again in someone’s Park Forest backyard, how they could fight a developer who was backed by industrial investors as well as federal Housing and Urban Development grants.

“He said ‘sue the bastards,’” Dolan Mendelson said. “And the TCPA did.”

But it wasn’t as simple as that.

“There were a gazillion meetings, and letters they wrote, and the rabble rousing they had to do,” she said.

For one thing the area was large, and based on the burgeoning success of Park Forest just to the north, the land was valuable. Aside from the HUD-backed Manilow effort, no single agency would be able to consolidate the Mall property, the remaining 5-acre wood lots and other disparate holdings that would make up Thorn Creek Woods.

Park Forest leaders, Dolan Mendelson said, were “super supportive from the beginning.” The Forest Preserve District of Will County was on board too, but at the same time the district was dealing with a proposed dam at Hickory Creek near Joliet and “they weren’t prepared to obligate for hundreds of acres” at Thorn Creek, she said. “Eventually they were convinced to do a $3 million bond issue, and some of that money went to Thorn Creek.”

The outreach effort from volunteers was epic, she said.

Original Walnut Hill Gang members Mary Lou and Jim Marzuki “spent $1,500 on long distance phone bills at one point in the ‘70s calling Washington, D.C.,” Dolan Mendelson said. Other backers burned up the paths to Springfield “with typewriters on their laps, going down to attend meetings and rabble rouse.”

Simon visited at the behest of the Thorn Creek backers — “They feted him and had dinner at someone’s house” — and was among a bevy of officials who were led down “deer trails and introduced to the woods.”

The combined efforts worked. The state chipped in needed funding along with Park Forest and even the nascent Park Forest South, now University Park. The Manilow development backers settled out of court and sold the company’s holdings in what would become Thorn Creek Woods.

An intergovernmental agreement was drafted to unite Park Forest, University Park and the Forest Preserve District of Will County as partners in the administration of the new Thorn Creek Woods Nature Preserve. The county administered the state-owned land and a neighboring resident, who was a member of the Thorn Creek Preservation Association, donated a foot of their property to the preserve so the grassroots group that fought for the preserve would have a seat at the table too.

The agreement was the first of its kind in Illinois, Dolan Mendelson said, and has been used as a model for other multiagency efforts in the years since, such as the Old Plank Road Trail from Frankfort to Chicago Heights.

In the following years, the woods became fronted by its signature structure, the 1865 church originally built by an Evangelical Lutheran congregation at Sauk Trail and Cicero Avenue in Richton Park. It was moved twice, including being rolled on logs felled from the forest, when it was transported from a nearby lot to its current location in 1972.

In the late 1970s Thorn Creek Woods was certified as an Illinois Nature Preserve, offering additional protection from future development, and the representatives of the owning agencies still meet monthly to administer the preserve.

The Preservation Association is still together, now known as Friends of Thorn Creek Woods. These days, members are devoted to helping with volunteers and programming. This year they’re marking the 55th anniversary of coming together to fight for the forest, including at an anniversary picnic scheduled for July 21 in Park Forest.

It’s a celebration of a time when the people got together to fight the power, and the people won. And it’s also a celebration of the 1952 Tribune prediction that eventually the area would be opened to the public.

Thanks to a dedicated group of neighbors, Thorn Creek Woods continues to be open to everybody.

Landmarks is a weekly column by Paul Eisenberg exploring the people, places and things that have left an indelible mark on the Southland. He can be reached at [email protected].

Paul Eisenberg , 2024-04-21 12:15:35

Source link