[ad_1]

Almost every Black person of a certain age remembers being terrified by something in The Wiz.

For me, it was the sharp-toothed trashcan monsters of the New York subway that antagonize Dorothy (Diana Ross) and her friends Lion (Ted Ross), Tinman (Nipsey Russell), and Scarecrow (Michael Jackson) in the 1978 movie musical that came out a few years after the show’s Broadway debut. For others, it was the wicked sweatshop mistress Evillene — don’t bring her no bad news — and her menacing band of simian motorcyclists.

For Melody Betts, who plays Evillene and Aunt Em in the Broadway revival opening April 17 at the Marquis Theatre, “the ‘Mean Ole Lion’ track scared me half to death.” Betts began listening to the soundtrack on vinyl when she was just a toddler in the late ’70s. “I would listen to the whole thing and I would sing along. And then when that part came, I would get up and go into the closet and hide because I was scared. And then when that song was over, I would come back out and finish listening to the rest on the soundtrack.”

Fans who’ve been hoping to revisit the soundtrack have nothing to fear. Nearly 50 years after it first opened on Broadway April 17, 1975, The Wiz, in all its “Black-is-beautiful” glory, has returned. It’s a show that, in a departure from the 1939 film based on The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, has always been more vibes and music than plot, a space to bask in Black excellence, elegance, fashion, dance, and futurism. The revival is queerer and funnier than ever, with an updated book full of new material by comedian, writer, and first Black woman to host a late night show, Amber Ruffin, and steered by Schele Williams in her Broadway directorial debut (Williams is directing two Broadway shows this season; the other is The Notebook).

While the musical, in all its iterations, holds a venerable place in the hearts and minds of Black families, with love for it passed down like a treasured potato salad recipe, others still chiefly remember The Wiz as a spectacular flop. The 1975 Broadway production, with its all-Black company starring André De Shields in the title role and Stephanie Mills as Dorothy, was seen as a revelation. Even the snappy new title —The Wiz — heralded a brand new day. With a book by William F. Brown, music and lyrics by Charlie Smalls, a thoroughly modern, soul-funkified iteration of the classic story bowed at the Majestic Theatre and took home seven Tony Awards, including one for Best Musical. But the 1978 film adaptation, directed by Sidney Lumet (who had never directed a movie musical before), lost a reported $10.4 million (approximately $48.4 million today). At the time, The Wiz was the most expensive movie musical ever made; a bomb that left a decades long fallout of producer anathema to splashy, big-budget Black projects. The lingering hangover of The Wiz is a disproportionate and chilling skepticism toward funding Black cinematic audacity as a whole. It calls to mind something Judas and the Black Messiah director Shaka King told The New Yorker’s Jelani Cobb in 2021: “Even the math in Hollywood is racist.”

Losing money is a regular occurrence on Broadway, so much so that when a show recoups its investment, there’s a press release trumpeting the occurrence. Yet everyone is aware of the historical stakes accompanying this show, and every Black show that manages to make it to Broadway. Part of the reason this revival is what Wayne Brady — who plays the titular Wiz in the revival — calls “a beautiful example of Black excellence” is because in this economy, it can’t afford to be anything else.

For years, rumors of a modern Broadway revival of The Wiz floated about New York’s small Black theater community, an urban legend that could one day see reality if enough folks just kept hope alive. In 2018, hope began its long journey toward reality when Ruffin, who also co-wrote the book for the Tony-winning Some Like It Hot revival, began developing a new book for St. Louis’s Muny Theatre, the oldest and largest outdoor musical theater in the United States. Like everything else in the world that relied on in-person interaction, the show encountered a setback when COVID hit. But that forced pause turned out to be a blessing.

“It takes this time to marinate so that it can really become exactly what you want,” Ruffin says. “And I guess it kind of makes you braver because you’ve been staring at it for so long. You might as well just go for it, is how I feel. Everything about this show is a very big swing, and that’s what makes it work.”

Visual details in the revival telegraph a contemporary, post-Obama Wiz before the first ba-da-bump-ba-dump of “Ease on Down the Road” bass line ever drops. The set, conceived by Oscar-winning Black Panther designer Hannah Beachler, is framed in a black-and-white pattern evoking body paint commonly seen at Afropunk, while Sharen Davis’s costuming speaks to the show’s overall ethos of compassionate, multifaceted expansiveness. Dorothy — sans Toto — sports a black watch plaid skater dress and Doc Martens, a choice sure to capture the attention of both vintage-curious zoomers and their Gen-X relatives.

“Our Dorothy is a teenager, and it was important to me to raise the stakes of the show to not give her a companion because that makes it a little safer,” Williams explains. (For the record, she loves dogs! She has nothing against canines as a species!) “She’s got this buddy with her and I really wanted her to feel isolated. I did not want to give her anything that could give her comfort and make her feel like she had something from home.”

Nichelle Lewis, in her Broadway debut as Dorothy, seems to combine the best of Judy Garland, Mills, and Ross’s performances even as she creates her own. Lewis, 24, was able to connect to the lonesomeness and alienation that endears Dorothy to so many. She grew up next to a farm in Virginia, and her mother raised Lewis and her sisters after Lewis’s father died when she was 10. “I wanted to create a Dorothy who was free in herself, who felt very confident in herself and knowing who she is, but also was just scared of what was happening around her,” Lewis says. She sings with an innocence and yearning rooted in experience.

Similarly, the Guyanese-Canadian Deborah Cox, who plays Glinda, found herself relating to the message of The Wiz — that you already have everything you need within you to face your fears — and Ruffin’s take on the quintessential Blackness of the original. “As a Black Caribbean person, a lot of different things resonate with me,” she says, adding that she felt inspired by the success of Trinidadian director Geoffrey Holder, who brought home Tonys for his direction and choreography of the original Broadway production, despite not being producer Ken Harper’s first choice for either position.

In Lumet’s film, the foursome traversed various neighborhoods of New York City. The 2024 revival jumps around the country, from the Tremé/Lafitte of New Orleans to the queer, fluorescent haired adolescent buskers and go-go bucket drummers of Washington, D.C.’s Gallery Place, to the smooth calypso rhythms that populate Brooklyn’s Crown Heights. “I mean, the music in the show spoke to me when I read the real history behind the costume design,” Cox says. “There are so many things that I can relate to in the show, even though I didn’t grow up here in the U.S. … I think that’s it from a soul level.”

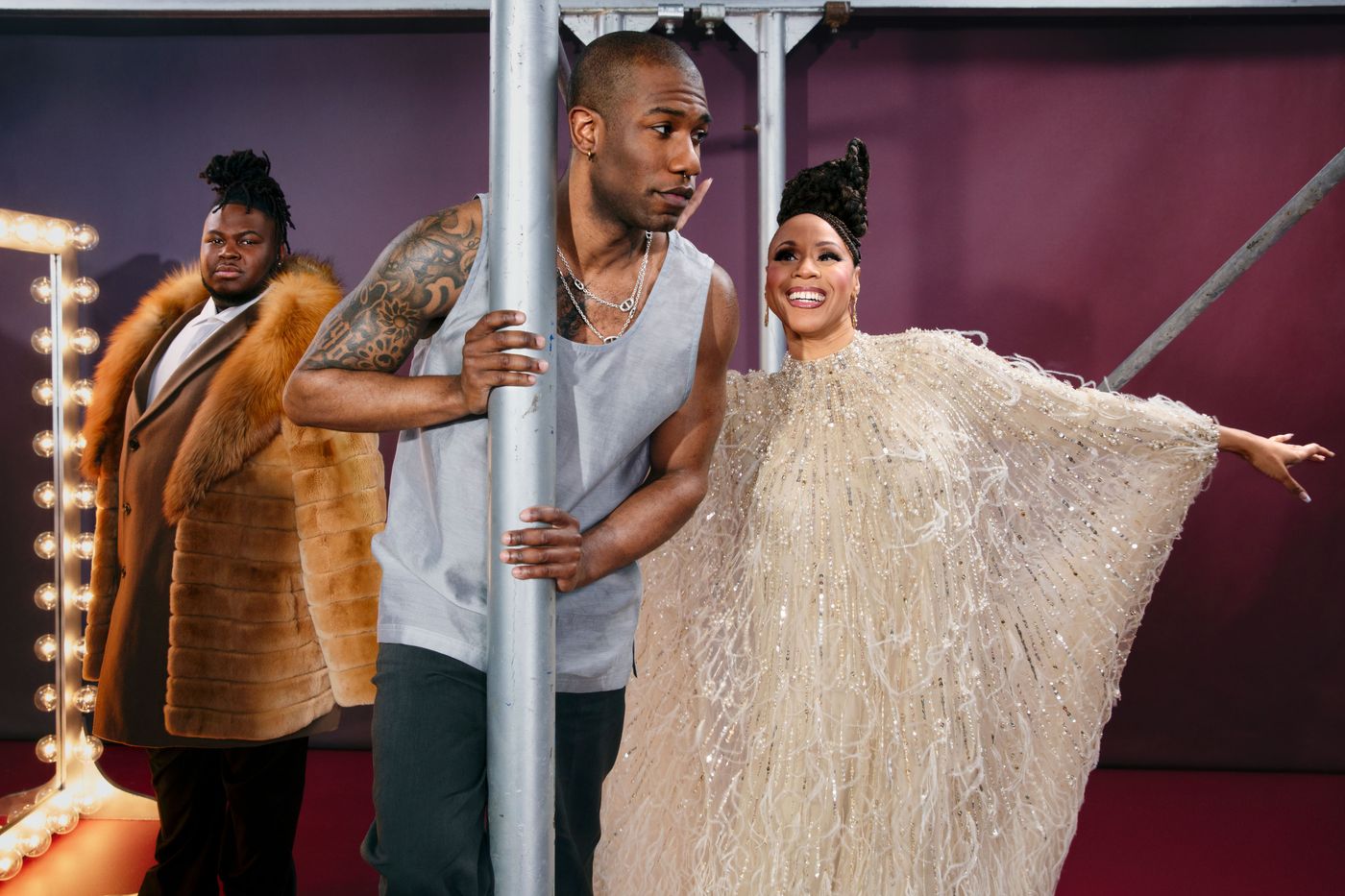

The movie version of The Wiz didn’t succeed at the box office, but it did become a cult classic. The influence of the film shows up in other works. The Moon in Caroline, or Change evokes Lena Horne’s cinematic iteration of Glinda, while the joyous clutter core of a Taylor Mac show recalls some of Tony Walton’s production design choices. The Wiz is for the misfits, a quality shared by many a queer kid who found refuge in its music, in the thousands of school theater productions that have been staged since 1975. And while The Wizard of Oz has always been queer — hello, friends of Dorothy — this new version of The Wiz boasts quite possibly the swishiest cowardly lion ever to grace a stage. The queer subtext that made The Wizard of Oz a camp classic has blossomed into text, as evidenced by the performances of Kyle Ramar Freeman (Lion) and Avery Wilson (Scarecrow). For one, Lion’s mane could not be more laid if he let Ms. Tina Knowles play in his locks.

“Bay-BEE! Twenty-two inches, the beard and the hair,” exclaims Freeman via Zoom, who has to arrive at every performance 30 minutes before his castmates to complete hair and makeup, which is all kept in place, sweat free, with some sort of industrial strength antiperspirant setting spray. Freeman also makes full use of Lion’s tail, to great comedic effect.

“When I was trying to discover what I would move and what I wanted to embody, as far as character goes, I am whirling that tail,” says Freeman, who came out to his “religious” family at 23, when he was just beginning to build an acting career in the theater. “I’m shaking that tail. I’m crying with the tail. I’m tracing my tail. I’m just having fun because I love a prop.”

The luxurious mane and the tail-flipping are all wrapped up in something bigger for Freeman, namely the show’s themes of bravery and self-acceptance. Coming out provided necessary liberation that eventually led to Freeman’s casting in The Wiz. “When I freed myself in my personal life from the constraints of trying to be something else, I was denying jobs, which I had never done in my nine years in New York City!” Freeman, whose Broadway credits include A Strange Loop and Fat Ham, says. “I was getting offers. It was like, ‘Oh, I get it.’ I have to do the self stuff first so that the other stuff can be presented to me and I can receive it and I can be ready for it.”

One of the oddball, oft-overlooked canonical notes of the Wizard is a bit where Scarecrow innocently talks about “going both ways.” The fact that Wilson identifies as bisexual puts a nice, tidy little bow on that. “I can be whoever the hell I decide to be. And that’s power,” Wilson says. “Getting into a space where there is a queer maybe undertone or just hints of it throughout a sprinkle of it, I thought it was great, to be honest.”

The stylistic influences of Beyoncé’s Homecoming show at Coachella — which opens with the horn fanfare from The Wiz — are abundant. There are the dancers who bring the yellow brick road to life, dressed as southern HBCU drum majors, complete with tall, furry bearskin hats. Brady’s Wiz delivers flourish after flourish with a cape, mace, and top hat that call back to the deceitful, feel-good chicanery of The Music Man as much as FAMU’s Marching 100. This revival was also choreographed by JaQuel Knight, the man who choreographed Homecoming and the music videos for “Formation” and “Single Ladies.” No wonder The Wiz feels like a show aimed squarely at the viewing pleasures and discernment of Queen Bey and her progeny; there is a true sense of shared creative DNA.

A high collar, striped afro, and high-heeled platform boots made De Shield’s originating turn as the Wiz into something indelible (yet another detail vindicating Holder’s vision), while Richard Pryor’s Wiz of the 1978 film, once unmasked, is memorable as a shrunken, whimpering pajama-clad normie. In 2015, NBC aired a live broadcast performance featuring a cross-dressed Queen Latifah as the Wiz, enjoying all the unchecked, unquestioned power charismatic men are able to occupy with little friction—well, at least until they’re revealed to be hucksters. For Brady, playing the Wiz is an artistic homecoming that allows him to fully own his capabilities as a theater savant who shares Robin Williams’s peripatetic comic energy. While he attained celebrity as a standout on the television improv comedy show Whose Line Is It Anyway?, Brady has always seemed most at home on the stage, in front of a theater audience, whether as Lola in Kinky Boots or spitting rhymes in Freestyle Love Supreme. “My Wiz is definitely part actor, part magician, part flim-flam man, with a little bit of Willy Wonka thrown in,” says Brady. Once he’s revealed as a con artist imposter, Brady takes all that energy and stuffs it into the preferred uniform of middle-age zaddies the world over: a track suit.

Tinman’s (Phillip Johnson Richardson) backwards cap calls to mind the Fresh Prince. And Cox’s Glinda? Think feathered sleeves that recall Yoncé’s stagewear at the 2018 Global Citizens Festival in South Africa.

Much like Shuffle Along, the 1921 grandparent of all Black Broadway shows, this revival’s road to the Great White Way did not begin not with a triumphant run of performances at one of New York’s storied downtown theaters. It was refined on the road — just like the original Broadway run. For the show’s company of travel-tested newcomers, that meant tour stops in Des Moines, Baltimore, Atlanta, Cleveland, San Francisco, Tempe, Arizona, Greenville, South Carolina, and more. Yes, they’re very happy to be on Broadway, but chatting with the cast, one gets the sense that they’re also happy simply to be sleeping in the same place for a few months. Because this revival kicked off with a national tour, the show’s set pieces were designed for a variety of stage sizes and dimensions. When our protagonists finally arrive at the Emerald City, we see how designer Daniel Brodie has rendered it in projections and video. It was a cost-effective method to create the world of Oz that can quickly scale up or down, but also a way to pay homage to the culture — each piece of architecture is shaped like a different Afrocentric hair style. And the Wiz sits upon a throne that appears to be encased in a large green perfume bottle topped with a crown of afro picks.

Across venues however, what remains consistent is that tapping one’s foot along to the familiar rhythms of “Ease on Down the Road,” or “You Can’t Win” still comes wrapped up, by the show’s end, with a big dose of sweet, full-throated nostalgia and a palpable journey toward self-belief. And that’s because, even when you strip away the costuming and all the other candy-like elements of The Wiz, there’s a soundtrack — or in this case, a forthcoming cast recording — that inspires the same kind of imagination that animated, enchanted, and even frightened a 3-year-old Betts.

“When I first did the Lion in sixth grade, I was a gay black boy from Miami, Florida who came from the church who was not able to be who I fully was,” Freeman says. “So the fact that I get to revisit this role, being who I am and comfortable in my skin and getting to tell this story from a different perspective is beautiful and rewarding to me … you can learn to love yourself. The world will open up for you and you’re going to have to do things that scare you, and that’s okay.”

Production Credits

Photography by Elliott Jerome Brown Jr.

,

Styling by Jessica Willis

,

Digital Tech Sam Kang

,

Photo Assistants Alberto Vargas and Ohene Okera

,

Styling Assistant Jaemi Rowe

,

Set Design WayOut Studio

,

Movement Director Vinson Fraley

,

Hair by Lacy Redway

,

Hair Assistants Shoshana Constaste, India Williams, Dominique LyVar, Francis Rodriguez

,

Makeup by Renee Garnes

,

Makeup Assistants Zarielle M, Niya Geiger, Joshua Hilario, Jesse Saeed Ramirez

,

Tailor Lindsay Wright

,

Production by Kindly Productions

,

The Cut, Editor-in-Chief Lindsay Peoples

,

The Cut, Photo Director Noelle Lacombe

,

The Cut, Deputy Culture Editor Brooke Marine

,

The Cut, Photo Editor Maridelis Morales Rosado

,

The Cut, Market Editor Cortne Bonilla

,

The Cut, Editorial Assistant Brooke LaMantia

[ad_2]

Soraya Nadia McDonald , 2024-04-18 18:00:48

Source link