For New York’s anniversary, we are celebrating the history of the city’s restaurants with a series of posts throughout the month. Read all of our “Who Ate Where” stories here.

In the extremely niche hothouse atmosphere of my late 20s in Manhattan, the nostalgic abstraction commonly known as “The Nineties” actually began on February 3 when the Roxy, a cavernous nightclub on West 18th Street (see also roller disco; hip-hop venue), opened its doors to the gays for the first of many Saturday-night parties known as Locomotion, an extravagant, two-year phenomenon that somehow felt — despite a velvet rope controlled by the inscrutably glamorous Chauncy — egalitarian and utopic. It also felt necessary, a pent-up celebration of life amid the grinding doom of AIDS. That same week, a chic minimalist take on the late-night diner — a kind of East Village Odeon — opened at 103 Second Avenue, at 6th Street: Jerry’s 103.

What these two places had in common (besides me) was a small subset of a highly specific clientele. Dimitri from the band Deee-Lite was a DJ at the Roxy, while he and his bandmates, Lady Miss Kier and Towa Tei, were also regulars at Jerry’s 103. (Indeed, their breakthrough single, “Groove Is in the Heart,” was the soundtrack to both places.) The painter Ross Bleckner, who could often be seen shirtless on the Roxy dance floor, was also a Jerry’s 103 habitué, usually accompanied by one or more of his revolving cortege of boy toy. The echt ’90s photographer David LaChapelle — whose surrealist-kitsch aesthetic was in keeping with the glitter-besprinkled ostentation of the Roxy — was often at the bar in Jerry’s with his adorable, snack-size assistant. And then there was Jean Paul Gaultier, the high priest of whimsical kink, who often wound up at the Roxy when he was in New York City; he once held a post-fashion-show dinner party at 103 where he invited a homeless man to join his group. Pourquois paaaas?

Indeed, if a darker vibe prevailed in the Roxy after-hours deeper into the crevices of the West Side, Jerry’s 103 was the insouciant before-hours, less Trent Reznor than Terence Trent D’arby. It was a staging ground for your team — a reconnaissance — before the long, headless night ahead, the place you’d go (with three hits of ecstasy in the watch pocket of your premium jeans) to eat a little something before heading off to the pleasure palaces.

Jerry Joseph, the proprietor of 103, had once been an art dealer who had owned a frame shop in Soho. In 1987, he opened the original Jerry’s at 101 Prince Street. With its red booths and zebra-skin wallpaper, it was always bursting with patronage at the lunch hour. But Soho was dead at night and Jerry yearned for a later scene. By divine coincidence, Bruce Mailman, owner of the Saint, the gay membership-only club where the Black Party was born that was located in the former Fillmore East space at 105 Second Avenue, also owned 103, an unremarkable, turn-of-the-20th-century five-story apartment building next door. He was looking to turn its corner storefront into an all-night “cafeteria” for the Saint’s patrons. At first he tried Brian McNally, but after that didn’t work out, Mailman asked Jerry if he’d like to take a whack at it, and Jerry’s 103 was born.

I’d arrived in the East Village two years earlier, in 1988. I wasn’t living in squalor, exactly, but I was functionally broke and surrounded by indignity. My $900-a-month, two-room apartment was next door to a crack den on 3rd Street and Avenue B. At night, fires burned in oil drums lit by squatters on the second floor, directly outside my living-room window, casting a flickering orange glow on the ceiling. To make a party, I would invite five to seven people over, get a beer ball from the distributor on Houston and … open the blinds! I regularly saw the drug dealer who had mugged me one night when I was buying cocaine from him at my laundromat, unperturbed, separating his whites. In those days, it was practically cheaper to go out if you got hungry: The $3 bowl of mushroom-barley soup at Kiev was a go-to. That stretch of Second Avenue — Teresa’s, Leshko’s, Moishe’s — was also where I experienced my first pop-up shop, a.k.a. the “thieves’ market,” where all the stuff stolen out of cars was displayed on the sidewalk. A dog-eared copy of Franny and Zooey and a pair of Levi’s that gave me lice — all mine for just $2.

I first spotted Jerry’s 103 from a passing cab at 2 a.m.; it was lit perfectly, spare and glowing from within, like an Edward Hopper painting with a few more people in it. Before Prune, before Porsena, there was Jerry’s 103, one of the first “nice” restaurants in the East Village. It opened just as my own life got an upgrade: a Condé Nast contract and a move into a loft on Great Jones Street with my new best friend, the actress Mo Gaffney. Even though our apartment was, practically speaking, in the same dirtbag precinct as the East Village, we were now technically living in Noho withLauren Hutton, Chuck Close, and Keith Richards as neighbors. Mo was fresh from the Off Broadway and HBO success of The Kathy & Mo Show. Harvey was suddenly calling; an hour later, a script would arrive by bike messenger from Tribeca. She was cast in a movie starring Sean Penn and Robin Wright, then another with Danny DeVito and Gregory Peck — a Norman Jewison picture! As a freshly minted Vogue contributor, I was having lunch with Anna at the Royalton and taking Apple town cars to photo shoots in the Hamptons. I found myself at lunch with Isaac Mizrahi at Bouley or Carnegie Hall in the same box with the Kissingers. One day, Mo and I went to a meeting with director Tony Bill and producer Diane Sokolow where they pitched us a sitcom to write. We were so dumbstruck and intoxicated by our sudden change in fortunes that when people asked what we were up to, Mo would sing the David Naughton song, “Makin’ It.” My point is we needed some place to “take” meetings and start social climbing and Jerry’s was our spot.

Meanwhile, the Roxy had become a hot ticket, like participatory theater for uptown voyeurs and the occasional A-list celebrity who wanted to see RuPaul dancing on a speaker box. An apotheosis of sorts was reached one … morning in April 1990 when Linda Evangelista and Christy Turlington climbed onto the swing that hung down into the middle of the dance floor. They rode it together, scissor-sister style, and it made all the papers Monday morning. A few months later, I was writing a piece for Vogue about Linda and Christy, partly inspired by the swing episode. “Everyone got a little too into it,” Linda said to me at Jerry’s 103, where we met for dinner on a steamy August weeknight. She arrived an hour late wearing the miniest of micro-miniskirts. She had a savage spray tan. We drank vodka and smoked Marlboro Reds. Linda ate two slices of some three-layer chocolate devil’s-food confection — literally the girl with the most cake. At one point, our waiter handed her a note from another patron who wished to remain anonymous. She read it aloud: “Miss Evangelista, how you move me to places unknown.” Her lashes fluttered into an eye roll for ages. “It’s probably from that geek with the glasses sitting at the bar.” I was mesmerized by the zero fucks she had left to give — at 25! There was just something sort of punk rock about her. Christy had said to me over the phone the day before, “You can feel very guilty about making so much money when you’re having fun.” When I shared this with Linda she took a bite of cake. “We have this expression, Christy and I.” She blinked a couple of times. “We don’t wake up for less than $10,000 a day.”

Anna Wintour wanted to cut that line (!) because she thought it made them sound horrible. I was like, I know! : D I eventually won the argument and ended my piece with Linda’s quip, which, poor thing, will get engraved on her tombstone. When I read the piece recently, I was surprised to see that the location wasn’t mentioned, just an anonymous downtown restaurant. And then I remembered: My editor cut it because he’d never heard of it. He was a persnickety queen and a snob. Jerry’s was not his scene.

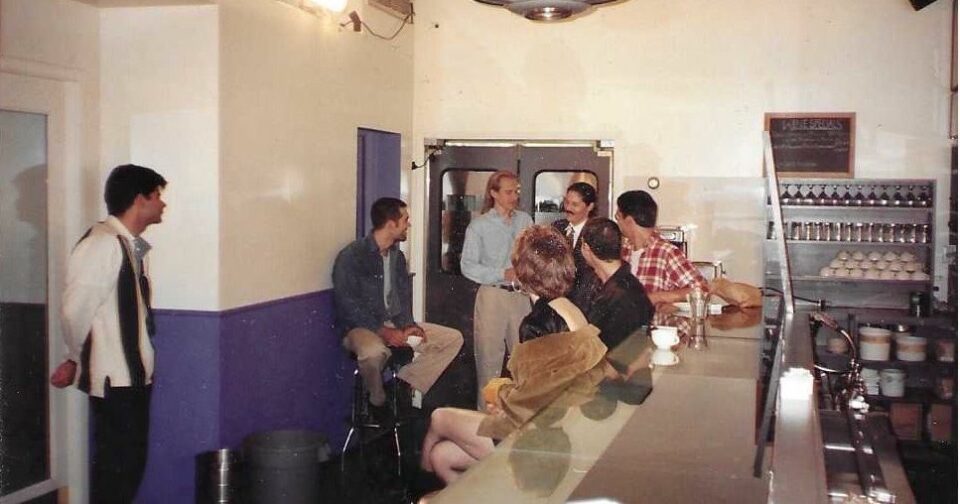

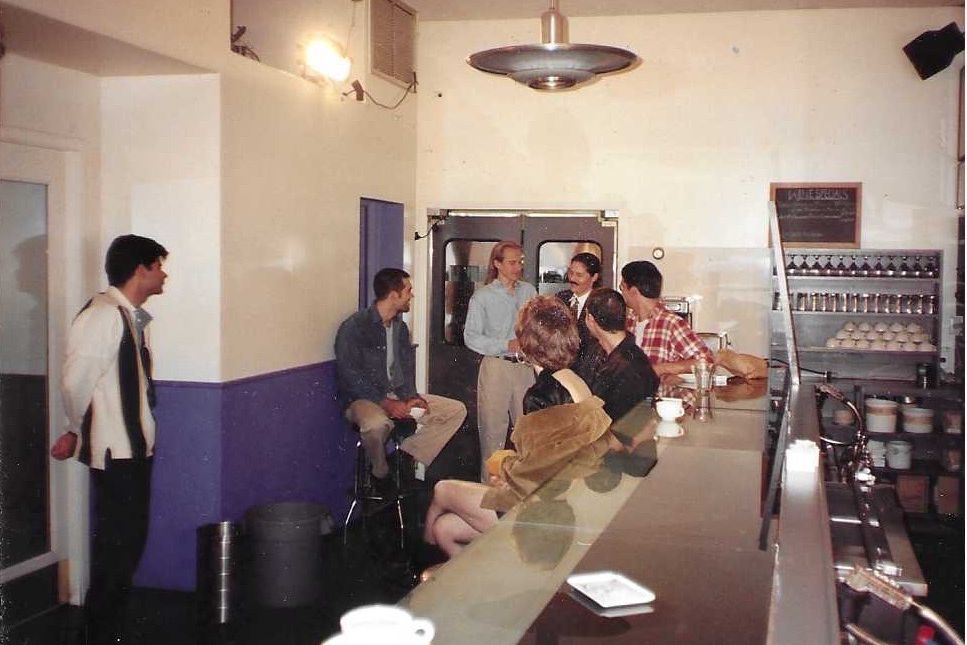

Jerry’s 103 was just three blocks from the loft I shared with Mo, and it quickly became an extension of our home. Sometime in the fall of 1990, we sat at the bar and fell under the spell of a bartender named Chase Booth, a willowy blond with a ’70s-babysitter ponytail and a dazzling smile — like, if Gwyneth Paltrow was a boy. We told him everything. We invited him to our house warming and he showed up on the wrong night, so the three of us partied anyway, a Chas(te) three-way. At Jerry’s, there was no door policy, no dick-softening exclusivity, but there was always a sense that the manager, Cliff, or the waitress Miche, a human three-card Monty, were taking good care of us. The Gavin Brown bar was long and boxy, made of plywood and topped with milk glass. The floor was kind of a failed terrazzo. The colorless walls were undecorated — the kind of space where unusual light fixtures did all the work. The “continental” food was elevated but unremarkable, except to say that it was consistent and delicious and exactly what you wanted. On weeknights, Jerry’s was not the chaotic gay bedlam of Friday and Saturday; it was just a perfect little restaurant. You’d see people like Jodie Foster or Robert Downey Jr. in a booth by themselves at weird hours.

I have stayed in touch with Chase all these years. He is married to the architect Gray Davis, whom he met at Jerry’s in 1991. Thirty-three years ago! I called him the other day to make sure I wasn’t making all of this up. “Gray came in with a whole posse of gays in their finery,” he said. “They would take ecstasy and go dancing. It was a very discreet place, and for whatever reason people got very comfortable and they enjoyed themselves. We’re alive! Let’s have sex with the busboys! Hey, put this up your nose! Waiters tripping on mushrooms! You don’t see that kind of thing in Manhattan these days. Everyone’s just quietly eating their civilized dinner. No one is dancing on tables. Or almost having a threesome with the bartender.”

More on ‘Who Ate Where’

- The Artist Hangout Where Julian Schnabel Cooked Sweetbreads

- Odessa Was a Headquarters for the Burnouts and Hangers-on

- The Super-Regular Who’s Eaten at the Same Restaurant for 31 Years

Jonathan Van Meter , 2024-04-17 20:44:17

Source link