[ad_1]

Go to any city in America and you can likely find a good Italian place, the hot Korean spot, and a semi-secret sushi counter. It’s only in New York that we have the rap-mogul restaurant, the supermodel café, the indie-director diner, and the club kids’ breakfast nook. We go to restaurants for oxtail or cocktails, but we also go to find our people. The great New York critic Vivian Gornick recently told my colleague Hilary Reid about the first time she was taken to Café Loup on West 13th Street by an editor: “He told me it was a ‘writer restaurant.’ I was thrilled. I thought, Oh boy, I’m being initiated.”

It was not always this way. As William Grimes writes in his 2009 book, Appetite City, the word restaurant entered popular usage only about 200 years ago. Paris was the western world’s culinary capital. New York subsisted on tavern grub: beef, bread, beer, oysters. Then the Delmonico brothers gussied up their downtown café with European-style glamour and a new era was born. Henri Soulé unveiled his Pavillon, Edna Lewis put she-crab soup on the menu at Gage & Tollner, and Masa Takayama turned a Columbus Circle mall into a sushi-baller landmark. Tastes change, styles evolve; the essential fact that our restaurants are our hubs and our hideouts does not.

Restaurants are extensions of our offices and refuges from our tiny kitchens, many of which are barely functional. With respect, our best spots are not defined only by their cooks and their hosts and their servers; they are defined by us, the indefatigable regulars. What would La Côte Basque have been without its swans? Mr Chow minus Andy and Jean-Michel? It’s impossible to imagine the Odeon without McInerney, Sylvia’s with no Sharpton.

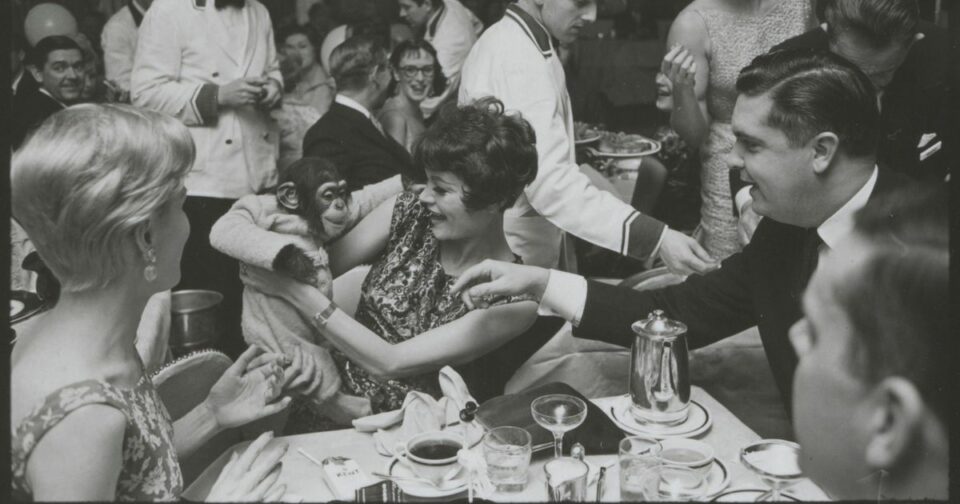

For our tenth “Yesteryear” issue, we dove into the haunts and the joints, choosing the moments when individual scenes flourished. Through dozens of snapshots, we found a history of the city that hasn’t otherwise been told. The restaurants here were great not because of what they were but because of who we were and who we became while we were there. Landmarks may fade, but the feeling of ease that comes from finding your place — or, failing that, the place where the SNL cast likes to hang out — is timeless and universal.

—Matthew Schneier

For most of my childhood, I was dragged to a Brighton Beach banquet hall at least monthly. A Russian uncle would ask, “Paydyom v’Nassional?” On went the sequined dresses and Men’s Wearhouse blazers, up went the magenta-tinted hair, out came the knockoff Chanel bags, and off we went, usually to the “Nassional.” Established in 1981 by members of the first immigrant wave to land in Little Odessa, the National presented a windowless façade, but wonders lay within: a two-tiered palace festooned with dizzying carpet patterns, crystal chandeliers, and blinding footlights. Hundreds of seats were crammed into long tables laden with French-inflected Soviet appetizers: smoked sturgeon and tongue; salmon roe and black bread; and — my favorite — Olivier salad, a mélange of eggs, pickles, potatoes, mayonnaise, peas, and bologna. (Trust me.) By the time the kebabs and the chicken Kiev arrived, everyone was full.

The patrons, ranging in age from roughly 1 to 96, danced off the gluttony, lubricated by vodka (a bottle per four or five seats). The highlight of the night was the floor show. A parade of performers sourced from across the Soviet imperium executed stiff but sultry choreography alongside synth-heavy bangers in both Russian and English.

In the early years, the National’s theme was material aspiration. Its regulars had engineering degrees but toiled 14 hours daily in cabs, auto shops, and restaurant kitchens, saving for the next generation as well as the occasional cheapish thrill of getting drunk in front of their kids while feathered-haired beauties leaped among lasers and fog machines.

For a certain set of private-school kids who came of age in the mid-’90s, the Serafina on 79th and Madison will always be Sofia.

The restaurant opened in 1995, the same year I started high school, and quickly became our social hub. My friends and I would come for dinner, marching up the narrow steps in bulbous Steve Maddens, carrying box-cut Kate Spades, with Ricky’s glitter on our eyelids. The hostess would herd us past the main dining room (where grown-ups sat), up another flight to the third story, which had tented ceilings and uneven brick floors. This was the domain of teenagers.

“It was the one place you’d see everyone from all the schools,” says Elana Wexler, a friend from school days. We all showed up: Riverdale, Trinity, Spence, etc. Even if you didn’t know the kids at othertables, you knew of them from promoters’ party flyers or high-school lore.

We’d crowd the long banquette, eating artichoke salad, pizza margherita, and paglia e fieno, green and white pasta. (It was the ’90s; carbs were fine.) We littered tables with beepers, Parliament Lights, and bullet-shaped tubes of M.A.C lipstick. Sofia was where we celebrated birthdays and AP tests, nursed crushes and broken hearts. It managed to feel adult and aspirational while still comfortable for someone using a fake ID to order a glass of Pinot Grigio. Of course, as adult as we thought we were being, the restaurant was an entirely sponsored experience. We paid with our parents’ cash.

Sofia was the first place I felt part of a scene. I learned about the magic of bumping into people and the specific energy of a New York evening that could go in an infinite number of directions — even if those nights mostly petered out into loitering on brownstone stoops.

In late 1998, following a dispute with a restaurant of the same name, Sofia was renamed Serafina. Now there are ten Serafinas in the city, along with outposts in White Plains, Scarsdale — even Tokyo and Kolkata. Where Sofia felt singular, Serafina has the whiff of a chain. My meals there now happen at 5 p.m. with crayons and kids’ menus. I still spot people from the Sofia days. We give weary smiles over tennis-racquet pasta or, in the spirit of high school, pretend we don’t know each other at all.

Like any talented theatrical restaurateur, Joe Baum had his share of hits: Windows on the World, Tavern on the Green, Fonda del Sol. He also had his share of flops, none more titanic or comically misconceived than the extravagantly over-the-top Roman establishment that opened in the fall of 1957 on the ground floor of Rockefeller Center. Like the Four Seasons, which Baum debuted two years later, the Forum of the Twelve Caesars was built to cater to the high-rolling, high-spending captains of industry who populated midtown during its corporate-restaurant heyday. Unlike Philip Johnson’s sleekly modern, famously tasteful space in the Seagram Building, Forum featured faux-mosaic murals, Baroque-like portraits of Rome’s first dozen emperors, Champagne buckets designed to resemble upturned centurion helmets, and water taps in the restrooms that Mimi Sheraton merrily reported were shaped like bronze dolphins.

Guests dined on bizarre creations such as “Oysters of Hercules” and “Fiddler Crab Lump à la Nero,” a dish that was served tableside and flaming, of course. Weirdly, the reviews weren’t horrible (Craig Claiborne praised the restaurant’s “lusty elegance”), though Michael Whiteman, a longtime restaurant consultant and Baum’s partner of 29 years, says it quickly became apparent that there weren’t enough corporate fat cats in midtown who “viewed themselves as Roman senators wandering around in togas, or whatever it was Roman senators used to wander around in,” to support it. When the managers of the Four Seasons offered to buy that restaurant in 1974, Baum’s former company, Restaurant Associates, made them take the Forum, too. They closed the place shortly after that, though for a long time, if you took a seat at the also-departed Rockefeller Center steakhouse AJ Maxwell’s, you could still see the faded murals — remnants of a vanished time.

Here’s what kind of an event Mark Twain’s 70th-birthday party, on December 5 at Delmonico’s, was: Before it even happened, the New York Times ran not one but two stories about the invitations. The guests ultimately numbered 170, and it was a true A-plus list of literary, powerful, and just plain rich New Yorkers. On the night of the dinner, Andrew Carnegie spoke. So did William Dean Howells, the novelist and Atlantic Monthly editor routinely called “the Dean of American Letters.” President Theodore Roosevelt couldn’t make it, but he sent a message to be read. George Harvey, the editor of Harper’s Weekly, hosted. Delmonico’s was almost 80 years old by that time and still the omphalos of American fine dining. Everyone received a foot-high bust of the guest of honor.

The former Samuel Clemens was by then one of the most famous men alive. He’d made a fortune, lost it in a series of bad business moves, and gone on lecture tours and published his memoirs to earn some money. By 1905, he was on his feet again, and the party was meant to celebrate what was, at the time, the extraordinarily advanced age of 70. He joked about that in his speech, bringing up his skepticism about the medical treatments of the era and his diet, which he said he’d finally moderated after many decades of indifference. He also, it appears, was an intermittent faster before its time. “For 30 years,” he noted, “I have taken coffee and bread at eight in the morning, and no bite nor sup until 7:30 in the evening. Eleven hours.”

What did Twain and his guests eat that evening, presumably after 7:30 p.m.? Delmonico’s served heavy food without a lot of inclination to seasonality, and it showed. Even though it was December, there were stuffed tomatoes. Oysters, of course — every New York meal of consequence in those years probably included them. There was turtle soup, then a staple of affluence, and fried Baltimore terrapin and quail and saddle of lamb. Parsleyed potatoes and creamed mushrooms on toast rounded it all out.

Wednesday night was our flagship party, Disco 2000 at Limelight. After three hours of getting ready at the Chelsea Hotel, where I lived throughout the ’90s, I’d join my fellow club kids at photographer Michael Fazakerley’s studio to have our looks documented. Emerging as a Technicolor chain gang, we would tread in our platform shoes to an outlaw party staged at a high-traffic hub like Twin Donut or the L train — think flash mobs but before they were invented. We’d flood the joint with splendor and party until the cops came, then drinks would fly into the air and a herd of club kids, ravers, and banjee boys would stampede toward Limelight.

Whisked through the crowds waiting to get in, we’d regroup for a surreal, yet surprisingly civilized, sit-down dinner party around 11:30 p.m. The strategy behind the dinners was to get as many fabulous people into the club as early as possible, so when the paying patrons made their way though the door, they weren’t confronted with an empty room. Seats were given to the top-notch club kids, hinting at our internal hierarchy. There’d always be a quirky special guest, usually a personality from a campy ’70s show like Three’s Company or The Jeffersons. These dinners had an Alice in Wonderland quality with all of us sitting at a table in colorful sparkling costumes, surrounded by onlookers, eating a macrobiotic meal and chatting with someone we’d grown up watching on television.

The energy would build throughout the night until everyone was completely lit — obliterated on E, a mushroom punch, or some other powder or potion that had been passed around. For those of us working, it was a signal that it was time to get paid. Some of us would go home, shower, then dance until noon at places like Sound Factory. Wherever your nose or your feet led you, eventually you had to eat breakfast, and that spot was usually Cafe Orlin on St. Marks Place, which was known for its cheap breakfasts and gender-nonconforming staff. There was a giant round table in the corner near the front windows where club personalities would often hold court and swap gossip about the previous night’s adventures.

There was already French food in New York — at the Colony, the big hotels, Delmonico’s to some degree — when the 1939 New York World’s Fair opened in Flushing Meadow. But it was there that Le Restaurant du Pavillon de France served un-Americanized, uncut Gallicness, run by a hotheaded restaurateur named Henri Soulé and prepped by a well-drilled team brought over aboard the grand Art Deco liner Normandie. There was capon in tarragon aspic; saddle of lamb; there were, of course, frogs’ legs. An order of foie gras was 75 cents. The restaurant served more than 136,000 customers from April through October and did it again for the Fair’s repeat engagement in 1940.

When it was time for Soulé and his chefs to go home, France was no longer France. The Nazis had reached Paris, and the Normandie was seized for conversion into an American troopship. Soulé opted to start fresh in New York; his restaurant, Le Pavillon, opened that year on West 55th. Affluent New York took notice, The New Yorker profiled Soulé, and the place was consistently, reliably full. He moved Le Pavillon to a larger location in 1957 and, in its old home, unveiled a very slightly less expensive restaurant, calling it “my Pavillon for the poor”: La Côte Basque opened in October 1958.

Midtown, within a decade or so, gathered a huge array of descendants: La Caravelle, Le Poulailler, La Seine, La Grenouille, Le Cygne, and Le Mistral were all opened by Soulé’s former staff members and their employees. André Soltner and André Surmain’s Lutèce, though not directly linked to Le Pavillon, opened in 1961 and was widely understood to be the best restaurant in the U.S. They became known, both affectionately and disdainfully, as the Frog Ponds, and the best regarded among them gradually took on the moniker Les Six.

The ladies who lunch (labeled as such in 1970 by Stephen Sondheim, who lived about 300 feet from Lutèce) were the core customers. The ancillary Jackie O.’s of New York — her sister Lee Radziwill, the social queen bee Babe Paley, so many others — treated La Côte Basque’s banquettes as their cafeteria, smoking their way through countless lunches and slicing up other members of their cohort as expertly as servers did their Dover sole.

In July 1989, as Bastille Day celebrations lit up Paris, an immigrant restaurateur named Florent Morellet dressed up as Marie Antoinette and threw a party in the meat market of downtown Manhattan.

Florent, his bistro-diner that felt like a Weimar speakeasy with a Debbie Harry soundtrack, had been a hit since opening on Gansevoort Street four years earlier. Madonna was an early customer, followed by seemingly every boldface name in New York: Calvin Klein, Johnny Depp, Keanu Reeves, Roy Lichtenstein, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, David Bowie and Iman, Prince. But business sagged in the late ’80s as recession loomed and NYPD efforts to clean up Times Square pushed the sex trade into the neighborhood, where meat-packers still hung carcasses from hooks under the sidewalk awnings.

“It was dead, it was summer, and we were having a very bad time,” Morellet, 70, recalled recently from his home in Bushwick. “To find a good time, I decided to focus on Bastille Day.”

It was a hit, and Florent’s annual Bastille Day parties blossomed into a street festival that, at its peak around 1997, he estimates attracted 20,000 people. The party downsized in 1999, but it remained the signature event of a restaurant that was like a gay Elaine’s with better food.

Even as the restaurant’s reputation grew, Morellet kept it feeling like a neighborhood hangout. Some of his artwork, detailed maps of imagined places, lined the walls. After being diagnosed with HIV in 1987, he updated his T-cell count on the specials board.

And then Florent appeared on Sex and the City — twice. In retrospect, it was a clear sign this was the Meatpacking District now. “It’s impossible to say when it changed. It’s like the frog that can’t figure out when water’s boiling,” said Morellet.

It was the rent that finally did in Florent — what had been $6,000 a month became a reported $30,000. At the same time, more businesses in the area meant more regulations. After a series of five parties, themed around the Kübler-Ross stages of grief, Florent closed at the end of June 2008, just two weeks before Bastille Day.

“Democracy, I hate it,” Morellet said. “It was so much easier when there was only one queen on the block.”

Esther Eng was said to be the first Chinese woman to direct movies in both the U.S. and China. Eng, who lived openly as a lesbian, dressed in masculine clothing, and went by the nickname Big Brother Ha, grew up in San Francisco, made movies in Hong Kong, and moved to New York by 1950.

As the story goes, Eng ran into an old friend, Bo Bo, a Chinese actor who was reluctant to return to China, which was then under Mao. She decided to open a restaurant to give her friend and his troupe work. Called Bo Bo, it was located on Pell Street in the heart of Chinatown. In time, the restaurant became a harbor for expat Chinese actors, a place where they could get help learning English and money to pay their rent. The food was notably excellent: egg roll stuffed with lobster, chow gai kew, snails in black-bean sauce, and duck with litchi. Eventually, it became known, too, for long waits, which Craig Claiborne said in his New York Times review was the only issue he had with the place.

Back in the early 1990s, when magazines were fat with ads, relevance, and prestige, there was no place where the raw social power of Condé Nast’s top editors was more on display than at 44. The restaurant was housed inside an Ian Schrager hotel called the Royalton at 44 West 44th Street, just around the corner from Condé’s offices. The hotel’s interior was designed by Philippe Starck. “An early-’90s masterpiece,” remembers Graydon Carter, editor of Vanity Fair starting in 1992.

It was run by Brian McNally, who had been encouraged to open it by his friend Vogue editor Anna Wintour. “She was there from day one, which, you know, certainly didn’t hurt,” McNally recalls. “Graydon was a good friend as well, and he came every day as soon as he took over Vanity Fair, so that starts a little bit of a thing, having those two there every day. And Tina Brown, too.” The most important thing about having lunch at 44 was where you sat. Dana Brown wrote about the status scramble in his memoir, Dilettante, beginning with how he was actually working at 44 when Carter took a shine to him and hired him at Vanity Fair. There were only four banquettes at 44; one belonged to Wintour, one to Carter, one to Tina Brown, then editor of The New Yorker. The remaining banquette “was left open for whatever big shot happened to be in that day — Jackie O., Karl Lagerfeld,” Brown wrote. When Condé boss Si Newhouse was lunching, he bumped everyone down a banquette.

The rest of the room was defined by proximity to those tables. Gabé Doppelt, a former Condé editor, says, “Sometimes, Brian would ask, ‘Whose number is this?’” when a reservation would come in. “I would look it up in the directory, and I’d say, ‘Oh, a junior editor at Glamour,’ which basically informed him that he could put them near the kitchen.” (“We weren’t that snobbish!” insists McNally, laughing.)

“Inevitably,” says Doppelt, who now works for the San Vicente Bungalows, “in the middle of the morning, Brian would call me in a panic and say, ‘I only have three booths, and Anna, Calvin, Donna, and Ralph are coming. What am I going to do?!’”

According to its slogan, Dubrow’s was the “Cafeteria of Refinement” — never mind that the BMT subway ran almost directly over its roof. The chainlet (established in 1929, dismantled in 1985) operated in several locations, but the one that lingers in the mind was at Kings Highway and East 16th Street. There, surrounded by showy Italianish murals and an elaborate tile water fountain, three generations of Flatbush residents ate well for not much. The food was comparable to what they’d get at an Automat or a coffee shop but with a slightly Jewish accent: coffee cake, blintzes, chopped liver. Dubrow’s was open 24 hours, arguably busiest on weekends after services let out at Temple Ahavath Sholom. That made it a useful place to mingle with — and court — voters. John F. Kennedy, campaigning on a Thursday night in October 1960, dropped by to shake hands and have dinner with Carmine De Sapio, head of the Tammany Hall political machine. JFK ordered a steak and a Heineken; he beat Nixon in Brooklyn two votes to one.

Then subtly looked around …

JG: My friends and I would go there at least once a week. At lunch, Sirio held the tables on the banquette for people who came a lot. You would always see, say, ten pairs of women or men or whoever that you knew. And the ones you knew, you were glad you knew them. It felt like a club. It was not just random people. And then there would be the odd one you’d never seen before, like Richard Nixon.

Kimberly Yaseen, past chair of various fundraisers for the American Cancer Society and the New York Philharmonic: Sophia Loren would be there, or Ron Perelman would be holding court, or Gayfryd Steinberg. You looked across the room and everybody just sparkled. They looked beautiful.

JG: People came in dressed for the occasion. All the women had a Bill Blass suit or an Oscar de la Renta dress. You didn’t go to that restaurant coming from the gym. You wouldn’t walk in there unless you were pulled together.

BT: It was chic. My husband always wore a tie and suit, and he always looked elegant. He was a real gentleman. And I look at these guys today, and some of them are very, very handsome. But they look like they just came out of the gym. Why? I mean, do you really think you look so gentlemanly and terrific and handsome that way? No, you don’t. It’s pitiful.

SM: You would always have to drop your napkin and look both ways. Henry Kissinger would be sitting in the front. Or the conductor Zubin Mehta. You felt really good about yourself just being there.

BT: There was a corner where everybody would look right away to see who was sitting there. But I wasn’t looking around much. I was so in love with my husband.

Someone might call Nancy Reagan on the house phone …

KY: My recollection is that I ate lunch there several times a week, not always with the same women. We would chitchat. And, you know, if you were trying to finance a charity ball or you wanted someone to be an honoree, you would take them to Le Cirque because it was a glamorous place.

SM: We went there for lunch for a reason. By the end of two hours, you had figured out your whole committee. It was done. We didn’t have texting back then. You took out a little piece of paper; you had a pen. We planned the sponsoring committee for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund — the one in New York, not in Washington — at lunch at Le Cirque. I remember Pat Buckley used the house phone and called Nancy Reagan and she agreed to join.

JG: If you were celebrating something or wanted to have a good giggle with your girlfriend, that was the place to go.

The food, the food …

BT: I remember always trying to lose weight. I don’t even think about it now. But in those days, because we ate out so much, I was always trying to figure out what was delicious but small.

KY: I didn’t eat very much — lots and lots of salad and grilled fish.

SM: The pasta primavera was the best in the city. That was the first time I ever had pine nuts that were roasted before they put them into the pasta. Oh, and there was the cheese soufflé.

JG: I remember going, and I won’t name names, but one person ordered three lettuce leaves in a salad. But they did have wonderful Italian food. My people weren’t so dietetic. We had the pasta primavera, and it’s pretty healthy because it had all the vegetables, right? It wasn’t like carbonara in cream sauce. When my mother-in-law, Lydia Gregory, was dying in 1979, Sirio heard that she was ill and he sent pasta primavera to her in the hospital. It was her favorite.

SM: And he did these amazing desserts. You didn’t just order an apple pie. When I had tables of ten or 15 women, he would bring out all these desserts, and each one was different. They had these desserts in the 1980s that weren’t so much about eating but about looking at them. There was one in the shape of a piano and another in the shape of a clown. Altogether, it was like a circus.

BT: The desserts always had something charming to decorate them. You would get your dessert, and Sirio would say, “Oh, look, isn’t that cute?”

It’s a cliché, but it’s true: A restaurant is a good spot to knock someone off. The target is accessible, possibly seated, and likely unable to make a run for it. That’s what happened in 1979 to Carmine Galante, a top boss in the Bonanno crime family. On July 12, he was finishing up a meal at Joe & Mary Italian-American Restaurant in Bushwick. A cigar he’d lit after lunch would end up outlasting him.

It’s certainly the way it went in April 1972 for Crazy Joe Gallo at Umbertos Clam House, a seafood place that had opened a couple of months earlier. He saw the men coming for him — on his birthday! — and tried to bolt, but he couldn’t get out the door until it was too late. Two weeks later, New York’s “Underground Gourmet” ran a review of the restaurant. “Service was straightforward and not unfriendly,” the authors noted, “but a slight strain in the atmosphere was undeniable if understandable.”

Joe & Mary is gone. Umbertos moved across the street but kept its notoriety. Sparks Steak House in midtown seems to exist with no such gangster stigma, however, even though it was the site of what might have been the last great public rubout: Paul Castellano, arriving for dinner in December 1985, stepped out of his black Lincoln Town Car and into three men’s gunfire. The hit, it eventually came out, had been ordered by John Gotti, who soon superseded Castellano as the top man in the Gambino family, a spot he held on to until the government put him away in the early ’90s.

“If you know where the lesbians are, please take me,” Edie Windsor asked a friend in the early ’60s. Divorced for a decade, Windsor was unsure where to meet other women without risking her career at IBM. She ended up at Portofino Restaurant on Thompson and Bleecker, where she met Thea Spyer. Portofino was a straight restaurant that cultivated a discreet but dedicated lesbian following. Passing in whispers between friends, word spread: The food was delicious, the crowd was artistic, and on Friday nights, the women were almost certainly gay.

In the early days, Portofino was managed by Elaine Kaufman, who was honing her knack for drawing writers, artists, and musicians. “It was a wild and fun and very scary time because you never knew when the place was going to be raided,” says Friday-night regular Carlotta Rossini, now 79. But as a restaurant, Portofino had a loophole that offered a layer of protection: “There was no dancing, so what were they going to raid?” A dispute over finances led Kaufman to end her romance with Portofino owner Alfredo Viazzi, and she stormed out of the relationship and the business. “I smashed every glass and plate in the place,” she told Vanity Fair in 2002. Kaufman started fresh uptown, while Portofino carried on into the ’70s.

When Cositas Ricas opened in 2000, it became a refuge for Jackson Heights’ Colombian community, a modest bakery where you could nurse a café con leche and a guava pastry for hours. The energy inside skewed campy: Employees dressed in beige-and-green uniforms, and hamburger-shaped neon signs adorned the walls. Customers often stopped by wearing waist-trainers and with their hair in rollers. Then, in 2006, True Colors, a popular gay bar, opened next door.

The restaurant quickly became — and remains — a queer haven: To this day, it’s not uncommon to see a table of trans women and gays sharing a bottle of aguardiente sitting next to a group of straight dudes cursing at the soccer games playing on TV monitors overhead, all while waitresses float effortlessly among the aisles calling everyone amor. Over the years, the owners expanded the menu, painted murals on the walls, and added a giant yellow cow above the front door to advertise the various cuts of steak Cositas Ricas now serves, transforming it from a cozy corner panadería into a bacchanal befitting Roosevelt Avenue. After ten o’clock, the restaurant becomes a party. Salsa and cumbia play as diners dance in their seats when their song is on. Tune your ears and you’ll hear accents from El Salvador and Uruguay and the Dominican Republic mingling with those of the cooks shouting out orders for bandeja paisa — the classic Colombian dish consisting of rice, beans, chicharrón, chorizo, fried egg, avocado, and a crispy arepa — in the open-concept kitchen.

In the past two decades, Cositas Ricas has hosted the likes of Action Bronson and J Balvin, who filmed the music video for “Nivel de Perreo” on the roof in 2022. The real stars of the show are the locals. Paula Caceres, a line cook who was raised in Jackson Heights, was a regular at the restaurant around 2010. “It’d be packed with people coming home from work, couples on dates, the gay hairstylists from the salons down the street,” they recall. “I swear you’d see a baby getting baptized at a table, just chilling.”

To a heedless visitor, every McDonald’s looks about the same. But for as long as the fast-food chain has been in New York (its first store opened here in 1972), certain locations have served different purposes — as a high-low venue for a black-tie benefit gala attended by Andy Warhol in 1976, a quasi rec center for elderly Korean patrons in Flushing in 2014, or simply as hubs for various, and often debaucherous, crews throughout the five boroughs.

In the late aughts, at around 2 or 3 a.m., when the Lower East Side nightlife scene known as Hell Square began shutting down, the McDonald’s on Delancey and Essex provided an antidote to closing time: You didn’t have to go home, and you absolutely could stay there. “It was another character

in our lives. It wasn’t just an establishment,” says Brenden Ramirez, a bartender who remembers eating “McGangbangs” (a folkloric McDonald’s item that involves shoving a McChicken into a McDouble) while patrons took swings at one another. Lola Jiblazee, who hosted parties at clubs like Hotel Chantelle and the DL, would often marshal groups of people who thought they were following her to an after-party for a late-night visit.

In Tribeca, the Chambers Street McDonald’s has long replaced suburban family basements for Stuyvesant High School students in need of somewhere to misbehave. “If before a school dance, you wanted to get a little buzz, that was the place to be,” says Emma Carlisle, who graduated in 2006. “Its value was that it was lawless,” says the writer Becky Cooper, who graduated from Stuy that same year and doesn’t remember ever eating any

food at that McDonald’s.

Uptown, from around 2013 to 2016, denizens of Murray Hill may recall a mostly finance-guy scene at the 33rd Street McDonald’s after a night at Bowery Electric or Phebe’s. “The Wolf of Wall Street had just come out,” says one former regular of that location. “It was all these kids who thought they were Gordon Gekko — rich kids in suits at the McDonald’s, pulling out their BlackBerrys.”

When I was 8 years old, I wrote a note saying I was going to have my own restaurant by the time I was 30. But as that birthday approached, I was looking and looking for a space and everything was too expensive. My best friend, Yvonne Force Villareal, said Chelsea was going to be the next big place, but I wasn’t totally convinced. I wasn’t looking to be cool. I was looking to be successful.

Our first night, Lot 61 had 500 people from all over. The only celebrity I ever knew, an old pal, a bestie, was Bruce Willis. He was really so instrumental in sending so many people. When Kevin Costner was in town for three months, he came in because Bruce Willis told him to. It just clicked from there. I had a great referral system because we made people feel comfortable, safe, and happy. And we never talked to the press.

We didn’t really have a cocktail hour because nobody was around Chelsea at five o’clock. The exception was Annie Leibovitz, who would bring in her whole crew after a shoot. She’d come around 4:30. I even opened up at three for her. She got us on the Vogue radar in the first few months. We then did a big after-party for Armani Exchange for 250 A-list people, true A-list: De Niro, Sophia Loren, Marty Scorsese.

We’d serve food all night, and at 10 p.m., it turned into a disco. Mark Ronson was our first DJ. We also had amazing art on the walls: Damien Hirst, Jorge Pardo, Rudolf Stingel, and Sean Landers. I wasn’t trying to do anything other than put together something that I thought people would like. I came from Bouley, four-star dining. I was not a club owner, but I was too afraid to do a classic restaurant. —As told to Ben Kesslen

The writers and artists who loitered around Macdougal Street in the 1950s have been called a lot of things: “irresponsible tea heads,” Allen Ginsberg used to say; “subterraneans,” Jack Kerouac called them; and “real bastards,” according to the artist Mary Frank. To most people, though, they are and will forever be the Beats — a group united not so much by artistic style as by proximity and a desire to drink, do drugs, screw around, write, and repeat.

Where, then, did food fit into the equation? Mostly, it didn’t. To them, it was just “something they put in their mouth,” says Frank, who was married to the photographer Robert Frank, himself a part of the Beat crowd, for 19 years. The restaurants, cafés, and bars they frequented throughout their 20s served more as backdrops, places where they could “proselytize and argue,” Frank says. Ginsberg trolled the all-night cafeterias around what he referred to as the “lumpen world” of Times Square, seeking a bit of thrill and sleaze and occasionally picking up guys. He even briefly worked at Bickford’s on Fifth Avenue, busing tables and watching, as he later wrote in Howl, the best minds of his generation sink in its “submarine light.” Places like Caffè Reggio, Minetta Tavern, Cedar Tavern, and the jazz club Five Spot Café became frequent haunts but none more influentially than San Remo Café, on the corner of Bleecker and Macdougal.

In journals and letters, Ginsberg and Kerouac often refer to it simply as “Remo.” Frank, who “barely drinks now and didn’t drink at all then,” remembers it as a “corner filled with people,” though “you couldn’t hardly see anyone because of the smoke.” Wherever they went, she says, Kerouac, Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs, Gregory Corso, Lucien Carr, and whoever else happened to be tagging along with them attracted an audience. “They performed in the way they talked,” Frank says. “Especially Ginsberg, who had a voice like a rabbi.” The Living Theatre, Judith Malina and Julian Beck’s avant-garde troupe that was at the center of the early Off Broadway movement, was more or less founded in the San Remo. So were the casual flings the couple’s open marriage allowed.

Remo was where Kerouac embarked on a tryst with Gore Vidal, which the two wrote about separately in later books — Kerouac vaguely denying it happened and Vidal asserting it very much did. Remo was also one of the places Kerouac got into drunken brawls and Ginsberg nursed any number of crushes. “I would have liked to know you that night, wish I could have communicated who I was,” he wrote about seeing Dylan Thomas at the café in 1952. “Ran into Dick Davalos in Remo the other night, and we stared at each other and in low voices exchanged compliments,” he said in a letter to Kerouac. “It was always a drama,” says Frank. “And we were addicted to drama.”

One winter night in 1993, when I was 29 and still finding my way, a man I’d been seeing tried to impress me, I think, by taking me to Café Tabac. Of course, I’d heard of it. The gossip columns were full of items about the glamorous shenanigans going on nightly at the funky-looking little bistro on East 9th Street, opened the previous year by Roy Liebenthal, a soulfully handsome 28-year-old model, and his business partner, Ernest Santaniello. Madonna, Bono, and the so-called Trinity — Naomi Campbell, Linda Evangelista, and Christy Turlington — were showing up on a regular basis. “It was like lightning striking the gold pot and the gold pipes burst open and all the gold coins spill out. That’s what it was,” the journalist George Wayne has said.

My eyes growing wide as Lucy’s at the Brown Derby, I saw Robert De Niro come in wearing a leather duster and go upstairs with Harvey Keitel and some women in furs. Then Jim Jarmusch arrived, followed by Willem Dafoe, Steve Buscemi, and Iggy Pop, like some Reservoir Dogs–inspired fever dream. Then I saw the Trinity lope in and climb the stairs, all laughing and smiling as if being that beautiful was even more fun than it seemed.

And there was Debi Mazar. Oh my God, I thought, does this mean Madonna’s coming?

I resolved in the middle of dinner that I had to somehow get up those stairs and into the inner sanctum, which had its own velvet rope, followed by a curtain, then another velvet rope. My date had only enough clout to score us a table downstairs — no small feat, but suddenly it wasn’t enough. So I told this guy (an older British journalist who resembled the avuncular actor Stephen Fry, ascot and all) that I was going to the ladies’ room.

And then — quickly working out that it wasn’t my youth or cuteness that would gain me entry but knowing someone up in the exclusive room — I told the doorman at the stairs that I was Jarmusch’s cousin and on my way to meet him. Both ropes (and the curtain) magically opened. (I guess it must have seemed impossible that anyone would make up a story that ridiculous?)

The rest of that night stays in my mind like glossy stills shot by some great nightlife photographer. I remember looking around and thinking, I want to write about this someday.

They called it Tuesday Lunch Club, a hang with the regularity of a sacrament. Just about every week starting in the late ’80s, the artists Bing Lee and Ik-Joong Kang would round up a crew of friends like Martin Wong, Ken Chu, and Arlan Huang to meet at a rotating series of Chinatown spots. There was Tai Tung, where the Hong Kong chef knew to lace his fish balls with orange peel and seaweed. Or Yuen Yuen, where their performance-artist friend Frog King used to write out the daily menu for the restaurant in exchange for a free meal. Or Canal Seafood, where Kang liked to order the squid. “The criteria was ‘affordable.’ Food has to be good. And,” says Lee, “that the waiter or waitress doesn’t bother us. If they kick us out when we finish, it won’t work.”

“And nobody really talked about art,” says Kang. “You talked about food!”

But they were making art — a lot of it. They were part of a churning, bubbling downtown scene full of ambitious Asian painters, sculptors, dancers, and performance artists whom at that point the mainstream art world mostly ignored. They ate. And they shared frustrations.

Soon, they started to channel those frustrations into action: In 1990, Lee, Chu, and the artist and scholar Margo Machida, among others, formed Godzilla, a collective they called an Asian American Arts Network, which they wanted to use to get more shows and more critical attention for Asian American artists. Godzilla grew quickly, since anybody who came to a meeting was automatically considered a member. It organized shows and publications and in 1991 widely distributed an open letter they’d written to David Ross, the director of the Whitney Museum, pointing out that the Biennial that year included only one Asian American artist. It got results — that letter, and their subsequent meeting with Ross, is one of many reasons why the 1993 Biennial included more Asian American artists than ever before.

Godzilla stopped meeting shortly after 9/11. But Lee and Kang still get lunch. Now 75 and 64, respectively, they like to meet at Spongies on Baxter Street, where they linger over a $1 Hong Kong–style sponge cake before they decide where to go for the main event. Kang says that to him, their regular meals together are “more important than Godzilla. The spirit is different. It’s not about showing what we believe. It’s about the heart.” He laughs. “And the mouth. And the stomach.”

Tucked on the quiet corner of Commerce and Barrow Streets in the West Village, across from two identical townhouses separated by a shared gated garden (fancifully rumored to have been built for warring twin sisters) and a few doors down from the Cherry Lane Theatre, was Grange Hall.

I was hired as a waiter before it opened in 1992, which, at the time, was something of a surprise. Typically, restaurants had a stunning Black woman at the host stand, eye candy for the white male patrons, but Black men were mostly relegated to being busboys or barbacks, even in bohemian downtown. Luckily, one of Grange’s owners, Jacqui Smith, took a shine to me.

Grange served comfort food in a Great Depression–speakeasy type setting — down to the portrait of FDR over the bar and the Berenice Abbott photography. (Abbott had lived in an apartment above the restaurant decades prior.) With its refurbished wood-and-leather booths, vintage wall sconces, and stunning bar, Grange had a warm glow of comfort and privacy without the pretense that usually goes with that. Those were

the last days of indoor smoking at restaurants, and the walls had a cigarette patina.

It immediately became popular: Lou Reed and Laurie Anderson, seemingly in a state of unease, liked to sit at one of the three bar booths, gazing contemplatively out the window; Rosie Perez preferred the dining room. Matthew Broderick had exquisite taste in wine and liked the booth nearest the kitchen door. He was always cordial, which I suppose one has to be when dining with one’s mother, which he often did.

By 1994, I had stopped waiting tables and become the weekend brunch manager (it gave me more time to work on my first novel, The View From Here). One sunny afternoon, rays filtering through the vintage milk bottles used as flower vases, Brad Pitt walked in holding the hand of Gwyneth Paltrow. I sensed a shift in the energy in the bar area before I even saw them. He demurely made his way through the crowd to the host stand and asked for a table for two. I scanned the dining room, assessing the progress of tables, and looked at my list. “That’ll be about 20 minutes,” I said. There was a pause. Perhaps three seconds, which can be a long time. He didn’t say anything. I didn’t say anything. Paltrow didn’t say anything. “Would you like to put your name down?” I asked. He looked to his side at her. “Yes,” he said, then after a shorter pause, as if embarrassed to even mention it, but almost appreciative, he said, “Brad.” I wrote it down, and they made their way back through the bar crowd, past the vintage telephone booth, and exited the bar entrance.

What stood out was not the two of them but how others reacted. Didn’t I know they were rumored to be dating? These were the years before smartphones made everyone a roving reporter and social-media paparazzo. Had it been dinner, I think no one would have cared, but at brunch, without the cloak of night, people easily notice. One woman even said, “You could have given them our table.”

For a moment, I thought, Perhaps I’d made a mistake. I must have, the way everyone around me was behaving. Surely, having them there would be good for business. This was on my mind as I glided through the dining room, clearing tables, to get the next guest in. Then I immediately let it go. They weren’t regular customers. I had to keep it moving.

Still, when they returned 20 minutes later, I was relieved. Not just for the sake of the restaurant but because they’d chosen to come back. Humility. A table had just opened up. I seated them and continued on my way. The energy immediately returned to normal. No one gawked. The rest of the day went off without a hitch. Days later, I found out that someone had called “Page Six.” I was sorry someone invaded their privacy, yet, in a way, I was pleased. I knew it would make my job easier. If Brad and Gwyneth can wait, trust and believe, so can you. “Name?”

1950s: Joe’s Restaurant in Brooklyn Heights

The spacious two-story diner near Borough Hall with an exhaustive menu and surf-and-turf specialties attracted politicians, Catholic organizations, and civic groups to its banquet tables. Joe’s most famous patron was Dodgers co-owner Branch Rickey, who had discussed signing Jackie Robinson at his favorite table. It was torn down in 1959 to make way for Cadman Plaza West.

1960s: Antun’s in Queens Village

The catering hall appealed to Democratic bigwigs and labor leaders who needed a banquet room spacious enough to fête governors and senators. JFK stopped by for a women’s luncheon three days before the 1960 election to shore up the Irish American voting bloc in what was then a key swing state. “Everything is always pretty good there,” says former Queens congressman Joe Crowley. “For a catering hall, they had excellent seafood.”

1970s: Foffe’s in Brooklyn Heights

After Meade Esposito became the state’s most powerful Democratic leader, he summoned aspiring candidates and judges he backed to lunch at a table facing the front window so he could see who was coming in. The Italian trattoria specialized in wild game, and Esposito frequently recommended a veal dish named after him. Sometimes he even dined with reporters, telling one Timesman in 1972 that if he didn’t like the story, he’d “break his ankles.”

1980s: Gargiulo’s in Coney Island

While Manhattan elites hobnobbed at Elaine’s or the Rainbow Room, Brooklyn bosses preferred a family-run red-sauce joint that hadn’t changed much since 1907. Anthony Genovesi made judges and legislators over antipasto, while Brooklyn’s health-conscious borough president Howard Golden preferred roast chicken with broccoli rabe. Party functionaries trekked to Coney Island for fundraisers, although the banquet hall was also a favorite of developer Fred Trump, whose son Donald would tag along with him.

1990s: Sylvia’s Restaurant in Harlem

When David Dinkins became the city’s first Black mayor in 1990, Sylvia’s — already a landmark that had been open nearly three decades — became a second City Hall. “Lunches were scheduled, but breakfasts were more organic,” former governor David Paterson says. “You went there, you looked up the three to four people you were going to interact with that day, and you all kind of changed seating to talk about issues you’d deal with later.” Harlem’s next generation of political leaders — Paterson, Greg Meeks, Keith Wright, and Al Sharpton — were regulars. “Reverend Jackson, who was a soul-food connoisseur, would sit and lecture me on who I should become,” Sharpton recalls.

2000s: City Hall Restaurant in Tribeca

The bistro’s tall ceilings, cozy booths, and brass fixtures embodied the clubby atmosphere of the Bloomberg era, when technocrats and the lobbyists seeking to influence them gathered. It opened in 1998 but earned enormous goodwill among the political class for being one of the few downtown spots to stay open after 9/11. “I remember the scene a lot better than the food,” Bloomberg’s former deputy mayor Howard Wolfson says.

Right out of the gate, Indochine was one of the hottest spots in the city — alongside Area and Danceteria. But while those places were wild and messy, Indochine, which served Vietnamese food from its perch on Lafayette Street, was chic. The opening-night crowd in 1984 included Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Kenny Scharf. Debi Mazar visited throughout the ’80s, sometimes with Madonna in tow. “I loved walking up those stairs with the red light,” Mazar recalls. “And then there’s some gorgeous model going, ‘Hello, let me take you to your seat.’ And me just going, Why can’t I look like her? Why is she a waitress?” (The staff has long been intimidatingly gorgeous. “Whoever did the hiring must’ve been a casting director,” Bethann Hardison told me.)

You could see U2 sitting in a booth listening to a cassette of their still-unreleased record on a boom box, or an extremely pregnant Sarah Jessica Parker dining with husband Matthew Broderick the night before giving birth to their son, James. (Gossip columnists called the restaurant the next day asking if she’d eaten something spicy that triggered the labor.) One night when I was there with my favorite bodybuilder bottom gay porn star who was in town to film a gang bang, the king and queen of Sweden were in another booth with their daughter Madeleine. Willem Dafoe liked to sit at the bar behind the giant floral arrangement, where he would study the script for the play he was working on. Donatella Versace liked a table in the back when she brought her family in for Sunday dinners.

Jorg Rae, the bartender turned manager, remembers the time Catherine Deneuve almost didn’t get a seat. “I was standing at the door, and I see her just peeking into the window. The bar’s crowded and busy, and I see her turning around and leaving. I was thinking, Not on my watch. And I ran after her and I was like, ‘Miss Deneuve, were you looking for a table?’ She said, ‘Yes, but it looks very crowded.’ I said, ‘No, I have a great table for you.’ And she goes, ‘Well, can I smoke there?’ I said, ‘But of course.’”

Pre-Bloomberg, the restaurant was blanketed in smoke. “Indochine was always a restaurant where people smoked because cool people smoked back then,” Jean-Marc Houmard says. (He has run the restaurant since 1992, when owner Brian McNally sold it to him and two fellow employees, Michael Callahan and chef Hui Chi Le.) This applied to the staff, too: “They would light the cigarettes in between taking orders, and the bartenders would smoke in between shaking cocktails — and when there was that law that you had to have a nonsmoking section, the best tables were always in the smoking section. I remember these two old ladies, they were in their 80s, they came in, and I asked if they wanted to be in the nonsmoking section, and they said, ‘No, no, we want to be in the smoking section even though we don’t smoke because that’s where everybody who is interesting sits.’”

[ad_2]

By The Editors , 2024-04-08 13:00:32

Source link