When Walela Nehanda was 23, they were diagnosed with advanced-stage leukemia. Turning 30 — and publishing a memoir about the experience — seemed unimaginable to them at the time. But Nehanda’s 20s have been eventful enough to fill several volumes. Their debut, Bless the Blood, pulls from journal entries and poems written during their illness, tracing their epic journey through the U.S. medical-industrial complex. “I was getting into a lot of what it meant to be sick and disabled with all the marginalizations I also held,” says Nehanda. “I resolved that I wanted to essentially publish my diary. It’s a love letter to younger Black cancer patients where they can be a mess and it’s okay as well as historical documentation that I was here. This was really how cancer went; this is not some inspirational nonsense.”

Nehanda would rather use their book to shine a light on the ways our medical systems consistently fail patients. In visceral poems and essays, they methodically undress the systems’ violent limitations. The book is also deeply grounded in Nehanda’s conceptions of community and care, which they often found lacking in their life, especially as COVID-19 entered the picture. Retreating into their own head — into their spiritual practice and the process of writing Bless the Blood — is, says Nehanda, how they survived. “It’s a really heavy book, but ironically enough, I had the best time putting it together,” they say. They even created a playlist to go along with it. “It’s definitely my whole soul. I wanted people to get to know all of me in a way that I will probably never let happen again.”

The book was foremost inspired by and modeled after Audre Lorde’s Cancer Journals, which Nehanda read about a year into their diagnosis. “I was looking for Black people who had gone through cancer, and I wasn’t finding anyone,” they say. “In the media, we’re not around. So I was like, What does that communicate about survival?” Nehanda was moved by Lorde’s courage and willingness to communicate the grief and rage her diagnosis brought on, even when her feelings weren’t tidy and easy to sympathize with, and her desire to move through cancer with dignity. “I was chronically suicidal writing this book but also while I was going through cancer,” says Nehanda. “That’s something people don’t want to hear. I think people want to hear that the cancer patient is just grateful to be alive. Audre really helped me say it as it was.”

For our first installment of “Works Cited,” Nehanda shares the media that helped inspire or influenced their writing.

Illness As Metaphor, by Susan Sontag

Huge one. That’s one of the most pivotal texts for this book. Susan Sontag does such a brilliant job of unpacking what illness means in a society, and I really appreciated how she goes from tuberculosis to cancer to HIV/AIDS. I hope we can make all these connections and then connect further to COVID. My book makes a small attempt at that with poetry. Illness As Metaphor was very comforting to me because cancer is characterized as everything that’s bad, everything that’s evil. We see it in politics, in pop culture.

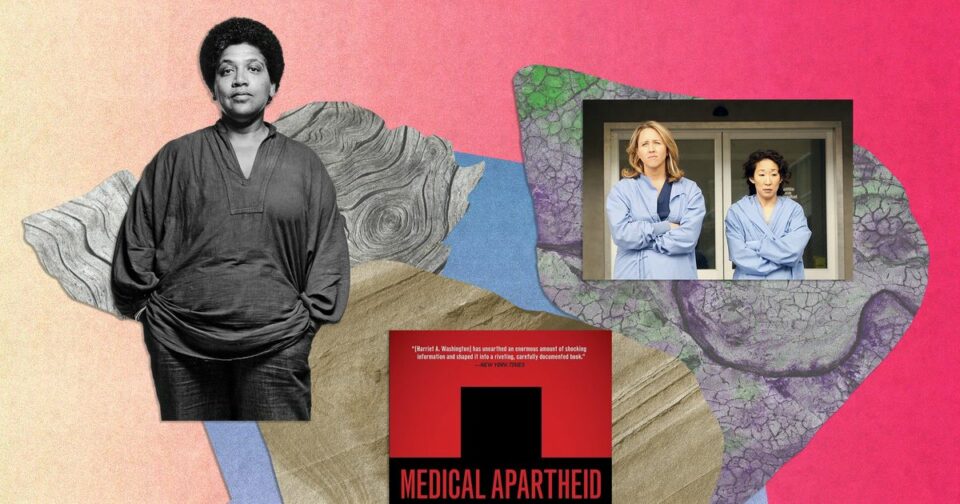

Medical Apartheid, by Harriet A. Washington

I read Medical Apartheid in 2019 or 2020. It is a hard read because it’s true. Our whole conception of health is rooted in experimentation on Black people, through enslavement, in carceral systems, through botched studies like Tuskegee where the agenda is to present Black people as a syphilis-soaked race. There’s always a political agenda with health. When I was writing this book, I wanted it to be very clear that this is not an abnormal experience, unfortunately. It was very important for me to not only share that documentation of myself but of my ancestors who were impacted by medical racism. I talked about Medical Apartheid a lot and the ways in which Black experimentation and Black health have always been this site of deep extraction and exploitation and death and trauma. When we don’t know what we’re experiencing and when someone names it, we’re like, Now I can do something about it.

What Harriet Washington does a great job of is showing that these ailments were made up about Black people — like “drapetomania,” runaway-slave syndrome. They were pathologizing a righteous desire to leave fucked-up conditions. It still happens to this day. That really enraged me. I don’t want people to view Bless the Blood as an isolated incident. This is a by-product of a long history of American culture and American politics. It’s set up this way.

“Betterrr,” by Orion Sun

“Betterrr” makes me cry every time I listen to it. I think it’s a really great send-off. You could have been better, and I could have been better. In death, we can make someone into a saint; no, let’s just receive me as I am. I think that song does a really beautiful job of that. I definitely do want to play it at my funeral if that ever happens. If I ever wanted someone to listen to me if I was gone and be like, “Walela is talking to me,” it’s that song. I’ve had friends who have died young, and I firmly believe they are around when I call them in with certain songs. In many ways, “Betterrr” and all the other songs in this book are like a grimoire where, when I’m gone, anyone can call me in and I’ll be right there.

Grey’s Anatomy

When I came home from the hospital, I turned on the TV and Grey’s Anatomy was on. I watched Grey’s Anatomy religiously when I first started writing poetry at 19. Love Shonda, Scandal, all of it, I’m there. The episode that was on was about a cancer patient who was dying. I was home from the hospital, newly diagnosed and having almost died, like, Shit, well, I guess we’re gonna dive into this. This patient was being overly bubbly about having a really serious illness. And at one point, I think Meredith or Christina or one of them gives a very somber look and says, “It’s not fair.” I started crying because I was like, “This shit is not fair.” That was my first moment to be able to say that. Because when you’re in a hospital, you kind of have to have this sense of delusion to get out. You have to have this infallible optimism. That episode was my first moment being like, I’m forever changed.

“The Rose That Grew From Concrete,” by Tupac Shakur and Nikki Giovanni

Tupac has always been a pivotal artist in my life, a lot of his interviews in particular. Pac comes from a very, very political background. There are some really amazing speeches early on in his career. I was very impacted by one of his interviews where he says, “I may not be the person who changes the world, but I may spark the mind of the person who changes the world.” My own writing comes with that same hope.

Bizarrely enough, after I got diagnosed, I got connected with Leila Steinberg, who was Tupac’s first manager, and then I wound up meeting Mutulu Shakur, who was part of that Shakur clan. He’s referenced in the book because he was a disabled political prisoner.

“The Rose That Grew From Concrete”was a very pivotal poem for me. I actually wrote “Crawling Toward the Sky” when I was 23, and I felt it was very fitting to end the book. Most people think I’m later in life writing that. No, we actually end the book at the same age I was when I started it. It felt very full circle to my younger self. I would be listening to Tupac’s albums with my mom, and she’d be like, “That’s a poet.” And I was like, “Bet. I will do that.” So it’s very much a curtain close, musical-theater moment that honors everybody in the book.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Related

- This Pride Month, Can We Talk About Abolition?

Katja Vujić , 2024-03-06 13:00:11

Source link