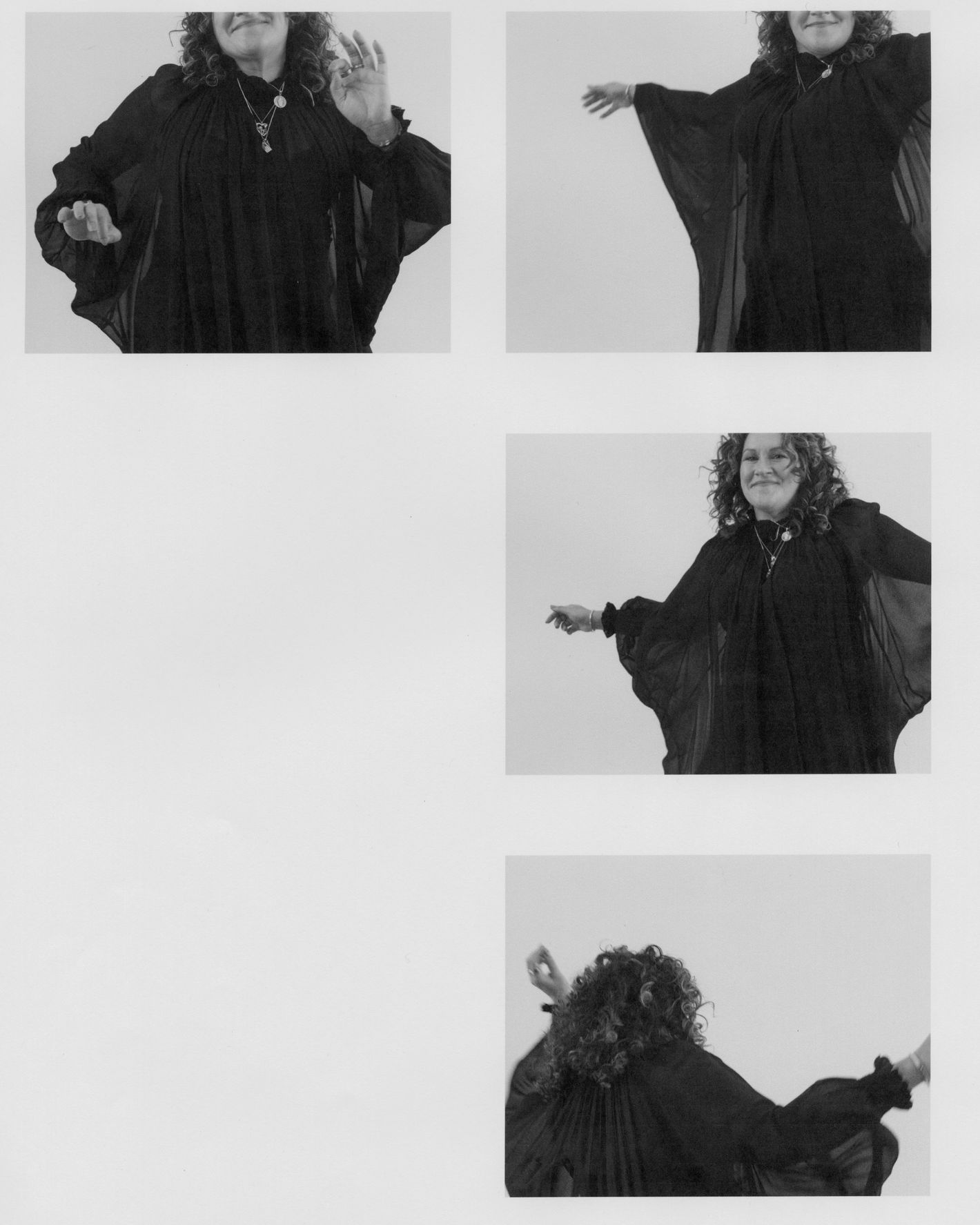

Xochitl Gonzalez is telling me she met a ghost. “I don’t know if I believe in magical realism or if I believe that there’s magic in the real world,” the Brooklyn-based writer says. And yet there’s no way to talk about her new novel, Anita de Monte Laughs Last, without getting serious about the supernatural. Gonzalez explains that the titular character was inspired by the late Cuban American artist Ana Mendieta, who has long been a “totem for artistic Latinas” and whose life was cut tragically short when she fell from the 34th-story window of her Greenwich Village apartment in 1985. Many thought her death was no accident: Her husband, the minimalist sculptor Carl Andre, was tried for and acquitted of killing her, and the case divided the New York art scene. For research, shortly after her first novel, Olga Dies Dreaming, became a best seller in the spring of 2022, Gonzalez traveled to the American Academy in Rome. The artist did a residency there shortly before her death, and a friend told Gonzalez that Mendieta’s spirit still lingered. So Gonzalez, 46, sat still at the spot she was told Mendieta haunted, thought about the artist, then heard a distinct voice pop into her head.

“The message was ‘You can borrow my story, but you have to use my voice,’” she tells me, the winter sun catching her blonde curls over spicy virgin margaritas in Prospect Heights. Apparently, Mendieta’s ghost vented her frustration that she hasn’t been able to tell her story on her own terms. “I wasn’t afraid, because that isn’t completely unusual for me,” Gonzalez says. “I’m not, like, a medium or anything, though people have told me if I tried to tap into that, maybe I could be. But metaphysically unusual things aren’t altogether uncommon in my life.” Receiving a blessing from Mendieta’s ghost completely changed the trajectory of the novel. “I revised the whole thing, writing her chapters in first person,” Gonzalez says. “That saved the book because it made me able to find humor.”

Gonzalez is funny — midway through lunch, I worry we’re laughing so loudly we’ll bother other patrons — so I find it hard to believe this didn’t shine through in early drafts. But she tells me that her first readers panned her original pass as, frankly, too depressing. Looking back, Gonzalez can see the root of the problem: She was angry when she wrote it. The day after Olga Dies Dreaming made it to the New York Times best-seller list, executives at Hulu told her that they wouldn’t pick up the pilot for its TV adaptation. They shot the pilot, whichGonzalez wrote and executive-produced and which starred Aubrey Plaza, Jesse Williams, and Ramón Rodríguez, months before the book came out. The rejection stung. She recognizes that anger was clouding her and that she had to get it out of her system before she could go back to writing a book people would actually enjoy reading.

The novel follows the parallel journeys of two heroines: Anita de Monte, a rising artist who is quickly forgotten after her sudden death shakes the art world, and Raquel Toro, a student attending Brown a decade later whose life begins to mirror Anita’s until she discovers the artist’s work while researching Anita’s more-famous artist husband. Where Anita was inspired by Mendieta, Raquel’s biography draws from Gonzalez’s own — though Gonzalez describes herself as “a little more charming” and “less reserved.” (She’s done this before; she has said the character of Olga Acevedo in her debut was a version of herself who never went to therapy.) Both Raquel and Gonzalez grew up working class in Brooklyn and studied art history at Brown, where they didn’t quite fit in. Raquel’s mother, Irma, is a lunch lady at the Met; Gonzalez was raised in South Brooklyn by her maternal grandparents, a nighttime janitor and a public-school lunch lady. In the book, Irma struggles to understand Raquel’s ambitions and the elite world she’s trying to navigate; Gonzalez’s grandmother“really resented all of my choices because she felt they were, like, cleaving us from each other,” she says, and tears start to well up in her eyes. “She wasn’t totally wrong.”

When Gonzalez went to Brown in the late ’90s to pursue writing, she was unprepared for the culture shock she experienced. She “didn’t have the map” to move seamlessly around campus like her classmates who came from prep and boarding schools. Gonzalez decided creative writing was not for her when she learned that her affluent white roommate had already attended a conference for emerging writers and won a Seventeen fiction-writing contest before setting foot on campus. (She says that roommate is still a good friend.) Gonzalez pursued art history and visual arts instead. Still, the sense of disconnect from her peers persisted. She spent summers working at Century 21 while her classmates traipsed around the globe. In a freshman class of about 80 people, she realized with horror that she was the only one who had never seen the Mona Lisa in person. “I was like, Well, I have to go to Europe for a study-abroad program!” she recalls, waving her carefully manicured dark nails for emphasis. “Now, is that the right motivation? I don’t know. But I didn’t want to feel deficient.” She hit as many countries as she could: Italy, Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands. When I tell her I recently visited Amsterdam for the first time, she replies that when she went as a student, she was in a “deep” van Gogh phase, which everyone should be allowed.

Gonzalez applies a fresh coat of bright-red lipstick — the shade is I Crave by Hourglass — before she gets up from the table to walk to our next destination: the Brooklyn Museum,one of her favorite places as a self-proclaimed “impromptu museum person.”She crosses Prospect Place like she owns it, dripping confidence, shooting an enthusiastic “Hi!” to a passerby whom she thinks she recognizes. The stranger scrunches up their face in confusion, and Gonzalez quickly apologizes before we both dissolve into giggles. As we walk, Gonzalez details the professional lives she lived after returning to Brooklyn after graduation: working in a gallery, planning weddings for New York’s wealthiest couples, marketing for corporations.

Then, shortly before Gonzalez’s 40th birthday in 2017, her grandmother died. She felt restless. Life was too short, she realized, not to take a shot at writing professionally. And suddenly she had a cushion. The family put her grandmother’s home on the market, and the sale helped Gonzalez transition out of the events business, get a day job as a fundraiser, and use her free time to write rather than chase down checks. Many wealthy people, she scoffs, are quite bad at paying on time — or even at all.

With the time to hone her craft, Gonzalez won a place at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and then entered the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 2019. There was no sense of deficiency this time: She arrived on campus with 200 pages of Olga already written and landed a two-book deal before graduating in 2021. The Atlantic’seditor-in-chief, Jeffrey Goldberg, asked Gonzalez to write a newsletter, Brooklyn, Everywhere, for which she was named a finalist for the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for commentary.

The money from Olga’sadvance and TV rights allowed Gonzalez to buy an apartment in Clinton Hill while many of her friends left New York City. “My life has changed while this place is changing,” she says. She’s already at work on her third book, which she describes as an attempt to preserve the memory of the borough of her youth. “The battle for Brooklyn is over, and I’ve lost,” she says as we walk through Grand Army Plaza, having finished our lunch of $16 fish tacos. “I’m not good at losing.” A friend’s dad worked as a security guard at the Met, she tells me, then waves her hand in the direction of an apartment complex designed by the Pritzker Prize–winning architect Richard Meier: “This was the home for people that had jobs like that. And now it’s not. It’s the home to the curators.”

When we enter the museum, Gonzalez takes me straight to Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party, the renowned feminist installation from 1979, which I confess I’ve never seen. Gonzalez thinks Mendieta is one of 999 women whose names are inscribed in the floor of the piece, though I Googled it after leaving and that’s not the case. As we walk around the table, we speak in whispers as we call out which names we find interesting (Ishtar, Queen Elizabeth I, Virginia Woolf) and point to the plates we find beautiful (Primordial Goddess, Sojourner Truth, Emily Dickinson). In the dim lighting, we’re transported to another time: back to when Mendieta herself was still alive, when the feminist movement was securing rights that made the future bright with possibility, when most people like us — Puerto Rican, working class — could only dream of occupying the spaces we do now. So much has changed since then. And yet the ghosts of these artists, saints, and activists are all around,telling us to create art in the face of the misogynist, classist, and racist forces still intent on setting us back.

Production Credits

Photography by Mara Corsino

,

Photo Assistant Rob Fay

,

Digital Tech Kevin Perez

,

The Cut, Editor-in-Chief Lindsay Peoples

,

The Cut, Photo Director Noelle Lacombe

,

The Cut, Photo Editor Maridelis Morales Rosado

,

The Cut, Features Editor Catherine Thompson

Andrea González-Ramírez , 2024-03-04 13:00:42

Source link