On the afternoon of December 3, I was on my hands and knees at the Sunset Tower Hotel, praying. It was the day before the Fashion Awards, an annual event put on by the British Fashion Council that honors designers, models, and others — I was up for Model of the Year. Yet all day, I had been making silent pleas not to win.

Please, God, don’t let me win this award, I prayed. I simply do not have the capacity.

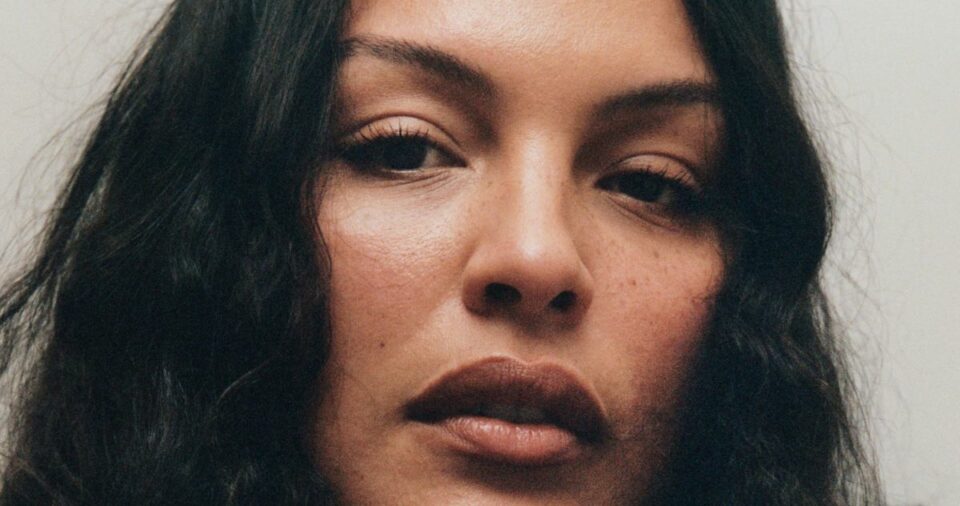

When I was 22, studying psychology and literature at the New School, makeup artist Pat McGrath saw me on Instagram and someone from her team sent me an email that would change my life. I started modeling, and in the nine years since, I’ve achieved things I’m deeply proud of: appearing on the covers of American and British Vogue (a few times!), walking runways worldwide, buying a home, even releasing a book. Yet, amid these milestones, I have been afraid of feeling found out. Constantly self-editing, trying to find my balance between tender self-acceptance and unbridled self-hatred. Each victory for representation comes with a new flood of vitriol and a new wave of doubt: Maybe they’re right; maybe I don’t deserve to be here at all.

I anticipated the backlash that the award would unleash: “Oh, this fat girl doesn’t deserve to win,” or “Inclusivity is ruining fashion.” But that night, winning was not on my radar; I genuinely believed it wasn’t going to happen. I’d been telling anyone who asked that my friend Anok Yai would rightly win — she had such a strong year, and I’m overwhelmingly proud of and inspired by her and the other nominees. Being a model comes with a rare type of loneliness: You sacrifice education, funerals, birthdays, friendships. Every day at work, you sit in strange hotels with new faces. Longevity in this game is rare, especially if you don’t fit the conventional mold of whiteness or thinness. All the while, many of us are helping our families back home. My fellow nominees all represent what it means to persevere in an industry that doesn’t center you. None of us white; none of us the children of famous parents. All of us working our asses off.

I didn’t even bother to prepare a speech. So when Damson Idris, the presenter, called out, “Model of the Year goes to … Paloma Elsesser!” I thought, Start thinking of what you’re going to say, bitch. I wove through the hall, lights flashing as peers and strangers stood on their feet and cheered. Damson handed me an intricate amber orb, my award, and I tucked it under my arm. Amid my sputtered words and sheer disbelief, I said, “I feel very honored and very shocked, but I’m also predominantly honored because I’m the first curve model to win this award.” I felt shy and overwhelmed, but I meant it.

Walking through the Royal Albert Hall felt like looking through the reel of my own career highlights. Everyone around me echoed the significance of my win, not just for myself but for representation in the industry. My phone was blowing up with texts from my team and loved ones. In those cherished moments, I felt excitement, affirmation, and joy.

The reality hit me the next morning on my way to the airport. The hate had sprawled across thousands of comments on TikTok, Instagram, and X, tearing apart my body, my face, my walk. People were having full-blown conversations in the comments sections of my own posts. Comments like “She’s a diversity pick” and “Real models work so hard to have the bodies that they have. You get to just sit around eating cheeseburgers” flooded my phone, and the onslaught of negativity didn’t come just from faceless trolls. In a TikTok that was liked 219,000 times, Kanye West fueled the fire, alleging I was part of a vast conspiracy to “push obesity to us.” This narrative has long followed me and many in the public eye whose bodies aren’t thin. Yet over the last few years, fatphobia has become acceptable again. Representation in media has become less alluring to folks, and its purpose is being reduced to “woke ideology.”

The following morning, I began sending my agent Mina waves of texts about how horrible I felt. I sobbed to her as I crept through Heathrow Airport unashamed at my unkempt emotions. Every doubt I had ever felt bubbled and spat like oil on a pan; my self-esteem was eviscerated. It felt as though my intrusive thoughts had become the subject of discourse for every rando on the internet (zero posts, zero followers, with handles like “fashionluvr2002”). Are these people not aware that I too think I’m ugly, fat, short, and a bad model sometimes?

I used to view myself as a flawed individual — this mentally ill, chubby brown girl with a messy house and an ongoing struggle to open my mail. Modeling changed my narrative and gave me a sense of purpose in challenging norms around our bodies that I too had been indoctrinated into. My body became a vessel for connection. A vessel for thought.

I’ve learned to be okay with pissing people off, even if it means losing opportunities. Since speaking out to say “Free Palestine,” I’ve lost two magazine covers and been met with hateful comments from strangers, like “I hope Hamas rapes you.” Yet there’s a difference between standing up for human rights and enduring relentless criticism for merely existing in my own body and not being the best in heels.

I shut off my public social-media accounts for the past two months. It’s painful to admit, but I found myself believing that I didn’t deserve to have almost a decade of hard work acknowledged. I felt like all that effort hadn’t mattered, like nothing mattered anymore. I’m left wondering what the point is of trying to shape a world where acceptance and critical thinking are possible, only to be plunged into the depths of self-loathing. What is the point if you end up in the same place, entangled in a misery we know all too well? Still, I can’t help but feel that if I hide away, fatphobia will win and so many potential gains will fade further into the distance.

I’m protective of the fashion industry, but it’s become evident that many of the same people who talk about making these huge strides in representation are also painfully resistant to change. And what about my role in their narrative? The industry may carve out space for a select few names like mine, but it firmly shuts the door on countless others. The pride in being part of a list of “firsts” is fading; being the first curve model for a campaign loses its significance when the brand fails to open its doors to the fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh.

Yes, I face criticism and doubt, but I keep going because it matters. I continue because it matters enough to me and because the people it impacts matter enough to me. Having a career I’m proud of means something. I’ve realized my success is significant in my small corner of the world, and that could be enough. There may be moments when I wish I could move through this industry with ease. But sometimes the work is painful and the accolades are met with fear. Perhaps I deserve recognition not just for the wins but for the effort, the struggle, and the hope that it might just matter to someone else. Is it all that bad if we start to believe we’re deserving of something?

More From the spring 2024 fashion issue

- Paloma Elsesser on the Price of Being ‘First’

- How I Got Scammed Out of $50,000

- Would You Spend $860 on These Stretchy Pants?

Paloma Elsesser , 2024-02-15 13:00:06

Source link