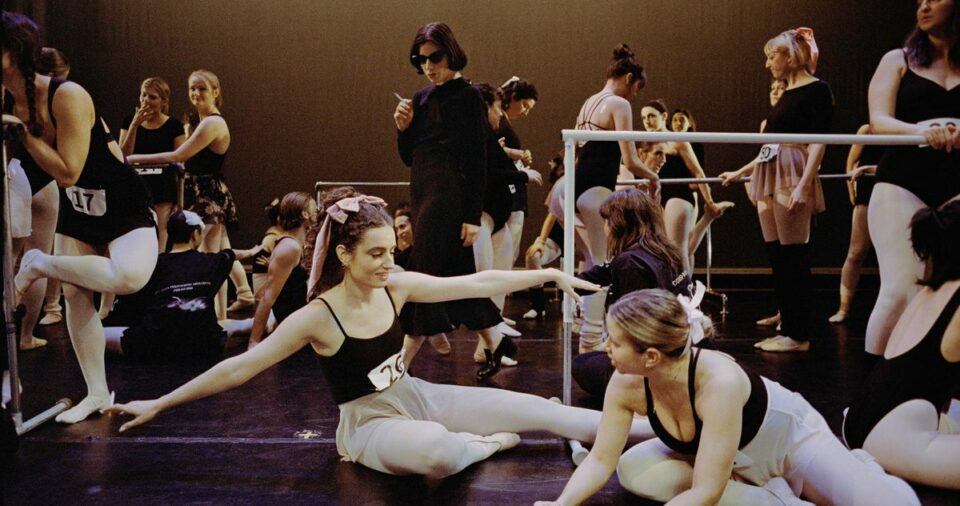

It’s a Thursday night at the LaGuardia Performing Arts Center in Long Island City, and by all appearances a children’s ballet recital is about to take place: tutus strewn across vanities; ballerinas scattered across the floor among small anthills of belongings, attacking one another’s buns with bobby pins, pruning and preening to the point of excess. A symphony of high-pitched whispers and giggles and the soft pitter-patter of ballet slippers striking linoleum tile fills the halls.

Only everyone here is somewhere between 23 and 48 years old — some of whom are dance novices gracing the stage for the very first time.

With 50 minutes before curtain, a stampede of friends, family, children, a few familiar faces (including Elliot Page), and beanie-laden Bushwick boyfriends descend upon the 740-seat auditorium, clutching bouquets purchased in the lobby. Backstage, the dancers’ jitters have intensified. In the holding room, a young woman in a pink wrap skirt dances to “Pop that Pussy,” dropping into the splits on the tiled floor and twerking. In another room, a group of powder-faced swans have devolved into a hysterical photo shoot, hissing and screeching at their own reflections in the mirror beneath bulbed vanity lights. Everyone copes with opening-night nerves in their own way.

“I want to write ‘WHORE’ on the mirror!” one suggests, a nod to the unraveling of Natalie Portman’s character in Darren Aronofsky’s psychological ballet thriller.

“Wait, slay,” another nods approvingly, as she snaps iPhone photos. “Give me Black Swan! Give me arched back!”

This fun-house-mirror interpretation of what ballet could be is the brainchild of Angela Trimbur, choreographer and founder of the semi-fictional Angela Trimbur Dance Academy (ATDA), beloved by Tommy Dorfman, Miranda July, and Evan Rachel Wood. Trimbur is also behind the cultish New York–based balletcore classes that inspired the evening’s affair.

It feels like a trophy almost. You get to experience the reward without going through the grueling things that most ballerinas go through.

Trimbur, 42, grew up dancing in Philadelphia, where her mother owned a small studio. Though she later pursued an acting career, dance was always there in the wings: In Los Angeles, she hosted “Slightly Guided Dance Parties” and founded a women’s dance team to perform at local basketball games, while choreographing and starring in short films and commercials. When she moved to New York in 2021, Trimbur quickly discovered a need for a casual dance community. She started teaching absurdist takes on childhood dance classes, from ’80s aerobics to an emo contemporary series she calls “Thirteen.” Then, last February, when she saw an early-aughts photo of Brittany Murphy sitting outside of a ballet studio and smoking a cigarette in legwarmers and Louboutins, she devised the idea for balletcore. A resurrection of ballet classes absent of all the self-loathing and body trauma seemed like a good use of her time.

“I like to stress that we love ballerinas, and they are athletes who have dedicated their lives to this,” Trimbur tells me at one point. “But for the graphic designers or people who haven’t chosen that lifestyle or dedicated their lives to ballet, it feels like a world that we don’t belong in.”

ATDA presents a Balletcore Recital: What Dreams May Come True, or “the recital” as Trimbur calls it, builds upon a thriving movement of adults reclaiming childhood extracurriculars and spaces for their own catharsis. (Ballet, in particular, has proven ripe for such a thing, with its overwhelming whiteness, engendered perfectionism, and obsession with thinness.) This rare opportunity to perform onstage granted the 97 dancers who auditioned, novice or otherwise, the neon exuberance of Dirty Dancing or Center Stage mixed with the radical self-compassion of a group of therapized adults. Everyone gets to be the Sugar Plum Fairy — or the Rat King, if so desired — when Angela Trimbur is in charge. Healing with a side of sequins.

“I wanted to be able to skip the beginner, intermediate, and advanced stuff and just go straight to the stage and the Swan Lakes and the Nutcrackers,” Trimbur says. “It feels like a trophy almost. You get to experience the reward without going through the grueling things that most ballerinas go through.”

To understand the ethos and origins of the “chill as fuck” ATDA recital, Trimbur suggests I attend one of her beloved January balletcore classes, often sold out thanks to now-viral TikToks posted by past attendees. As I walk into the Martha Graham Studio in the West Village, there’s a girlish buzz echoing around the room’s vaulted ceiling. It’s Degas day (as in painter Edward Degas’s late-1800s Danseuses), and the makeshift ballerinas squeal over each other’s lace chokers and tutus, one noting that hers is from “Daddy Bezos.” Four dancers in corseted leotards pose for selfies at the barre. “Can you move your Celsius out of frame?” one asks politely. “It’s not of the period.”

At the outset of class, Miss Angela storms through the doors in black sunglasses, fashionably late (“I came straight from directing at Juilliard,” she deadpans), with a Halloween-store cigarette in hand and a haughty mademoiselle accent that fades in and out. Unlike in most ballet classes where silent newcomers go unacknowledged, Trimbur asks for a round of applause for all new students, offering extra velvet ribbon for those who might want a choker to blend in with the regulars. Rather than ushering the class through a set of unfamiliar technical skills with French names (like “petit battement” or “rond de jambe”), Trimbur instead asks the class to lick the air, thrash their bodies without abandon, and grind their derrieres on the barre to the tune of an acoustic strings version of “Unholy,” by Sam Smith and Kim Petras. And despite the consistent giggles throughout class, the students seem determined to apply themselves fully to this practice — if not to nail the steps, then to perform as though gracing the stage of the Lincoln Center as an avant-garde, petulant ballerina.

While teaching choreography, Trimbur uses descriptions like “reach for the apple, take it away, throw it to the sky” in favor of traditional eight counts. She finds students are more likely to remember the steps when affixed to a feeling or an accessible action, as opposed to a “robotic number.” Trimbur teaches ballet hands, for example, as housing “the repressed middle finger,” the one that draws closest to the thumb. This “technique-less” style, as she calls it, looks as though classical ballet did a few lines and went to Joyface — delinquent, perhaps, but freer.

“There’s a sexuality to [the licking] for sure, but the tongue is also a part of the body that doesn’t ever come out in ballet. I wanted to introduce a part of the body that represents what stays inside, and let it out,” Trimbur says. “There’s a sexuality to it just because of things you do with your tongue, but the real logic behind it is the silliness. I’ll come up to people like, ‘Let me see the tongue!’”

As with her classes, a sense of play is baked into every step of the recital, from studio rehearsals to the final dress rehearsal onstage. The dancers ditch plain leotards or sweats in favor of oversize velvet bows, white ruffled bloomers, and tights of violet, cyan, dusty blue. The company members performing to Swan Lake’s finale music tousle their hair, shoot finger guns at themselves in the mirror, thrust their pelvic bones to the sky, and slap their bottoms, with the occasional piqué and pirouette thrown in.

“Get ugly!” Miss Angela screams backstage. “Your friends have seen you be cool. Let them see you be a silly gremlin!”

A lot of us wanted to feel free of any history, any baggage, any preconceived notions of who we are, so we could just become something else.

Backstage at the performing arts center, 24-year-old Sal Kimura, one of the Swans dancing to Tchaikovsky that night, proudly shows me their freshly shaved head and gemstone feathers they applied themself. Kimura showed up alone to one of Trimbur’s classes two years ago, having never attended a dance class before and terrified to move their body in a sexual manner. As a trans person, however, tonight Kimura looks down at their tutu and laughs, noting that the recital is the perfect opportunity to honor and send off all their “femme energy.”

“A lot of my friends are coming, and they know me to be this, like, butch 14-year-old boy, so it’s gonna be hilarious for them to see me in a tutu,” Kimura says. “But really, Angela’s whole philosophy has been a godsend in realizing there’s nothing anybody can’t be or do.”

In embracing the recital’s intended silliness with laser-like focus, Trimbur and her company members pulled off a momentous, and at times moving, show. The dancers I spoke to often began with how much fun they’d been having, only to dovetail into provocative meditations on life, identity, and purpose, detailing a life-changing experience that borders on the religious. What at first seemed to be an opportunity for adults to play make-believe under amber stage lights had morphed into the reclamation of femme-coded exercise: blown up, rebuilt, and dressed in drag.

“This has become my thing, because I didn’t really have a thing before,” 24-year-old Jess Stephenson, one of the Sleeping Beauties, says. They grew up dancing, following in the footsteps of their mother and grandmother, but quit after ballet class left them feeling like an outsider. “It’s really nice to have a hobby outside of work and love life that’s just something special for me.”

As each group took the stage, the childlike melodrama of the classes and rehearsals melted into genuine euphoria. It blossomed on their faces as they scanned the audience for parents who had flown in for the occasion, collecting bouquets from their supporters and carrying red roses backstage in their teeth. The dancers had crossed over into an ecstatic emotional plane, something many retired performers might remember from their time onstage, blinded by spotlights and choking down bubbles of pride, of exhaustion.

“A lot of us wanted to feel free of any history, any baggage, any preconceived notions of who we are, so we could just become something else,” says 35-year-old Alexis Freitag of the Vivaldi section. “I stopped dancing when I was really little because I had a bad experience … but this draw to dance was always there, and Angela just allows for anyone at any level or any degree of interest to create whatever they want in the space.”

“I see myself doing this forever,” she adds. “I will never give this up.”

After a finale number in which Trimbur rode across the stage on an electric scooter (it was intended to be a motorcycle as in Center Stage, she says, but there are some logistics too complicated for even Miss Angela), the show closed with a denouement — collaged footage of all of the company members as baby ballerinas, in feather boas and with imaginary microphones, projected onto the back wall of the stage. In ballet, as in literature, the denouement represents a final untangling of events. Angela Trimbur’s version, however, looks not so much like a conclusion but a prologue. A wink that implies this might actually be the beginning all over again.

Emily Leibert , 2024-02-14 19:00:28

Source link