[ad_1]

Women read the book because they wanted children, because their older sisters sent them copies, because they had idly paged through it at a cousin’s house and couldn’t put it down. Because it contained information about their bodies that they didn’t get in their all-girls high schools or sex-ed classes or OB/GYN visits. They bought the book because all their friends were using it instead of hormonal birth control — they thought, Sure, it seems better to be “natural” than to keep taking pills. They read it even though they weren’t really into health books and the whole thing seemed “a little woo-woo,” but the friend who swore by it had two Ivy League degrees and worked in finance, so why not give it a go? They brought it to their doctors and midwives. They used it to conceive their daughters and then passed it on to them when they started to consider having families. They clung to it like a best friend, carrying it around the city, dog-earing the pages.

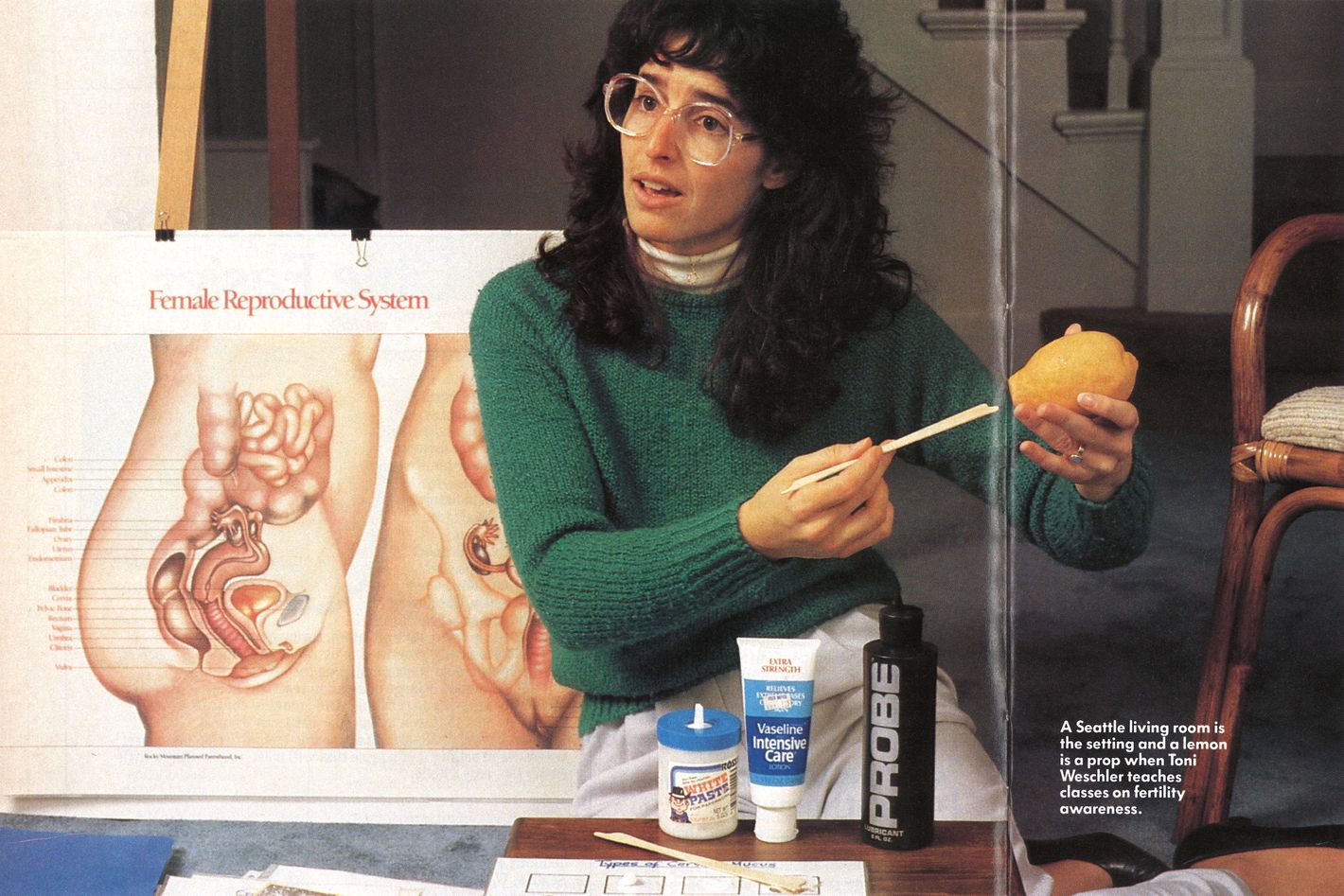

The book is Taking Charge of Your Fertility, a 557-page manual on the female reproductive system, first published in 1995 by a women’s-health educator named Toni Weschler. In 23 chapters — on everything from gynecological health to the menstrual cycle to sexual pleasure — TCOYF laid out instructions for an advanced form of period-tracking called the Fertility Awareness Method (FAM). It taught readers how to track, with just a thermometer and their fingers, the fluctuations of their hormones. Once a woman knew how to read the signs, this data could tell her when she was most fertile and when she was not. She could recognize that a sustained uptick in her basal body temperature for at least three days meant an egg had matured, been released from the ovary, and was now traveling through her Fallopian tube. She could observe her cervical fluid transform from a viscous white cream that would trap sperm to a translucent, stretchy ooze that would allow sperm to wriggle through. With this knowledge, she could conceive or avoid conceiving. She could also suss out health problems like polycystic ovarian syndrome by noticing long cycles without any temperature shifts. And she could watch as her cycles grew irregular and cervical fluid drier, foretelling the onset of menopause.

For decades, this tracking method was almost exclusively practiced by religious Catholics — until Weschler, along with a like-minded group of secular feminists, wrestled these insights about the female body away from anti-birth-control hard-liners and into the mainstream. In the nearly 30 years since its publication, TCOYF has been translated into 12 languages (not including a bootleg Russian version) and has never gone out of print. Fertility researchers recommend TCOYF to their patients, and high-tech thermometers like Tempdrop and Daysy have made basal-body-temperature monitoring a norm for those trying to conceive. A survey published by the CDC found that from 2015 to 2019, almost a fifth of respondents had used FAM at some point.

Today the book, which remains a useful reference for many readers, has also gotten folded into a more extreme politics. Like raw milk or off-the-grid living, TCOYF has ended up at the intersection of the Venn Diagram of the far left and the far right. For those on the left, FAM represents a female-centered, natural alternative to hormonal birth control: an anti-capitalist well of knowledge connecting women to their biology, safe from the interests of big pharma and a medical Establishment that ignores women. But the book has also been embraced by a conservative religious audience, which increasingly sees hormonal birth control as the next frontier of the fight against abortion and has taken to social media to undermine trust in contraceptives like IUDs and the Pill. For them, FAM is a tool that allows one to control when you conceive while still working within the divine order set by God.

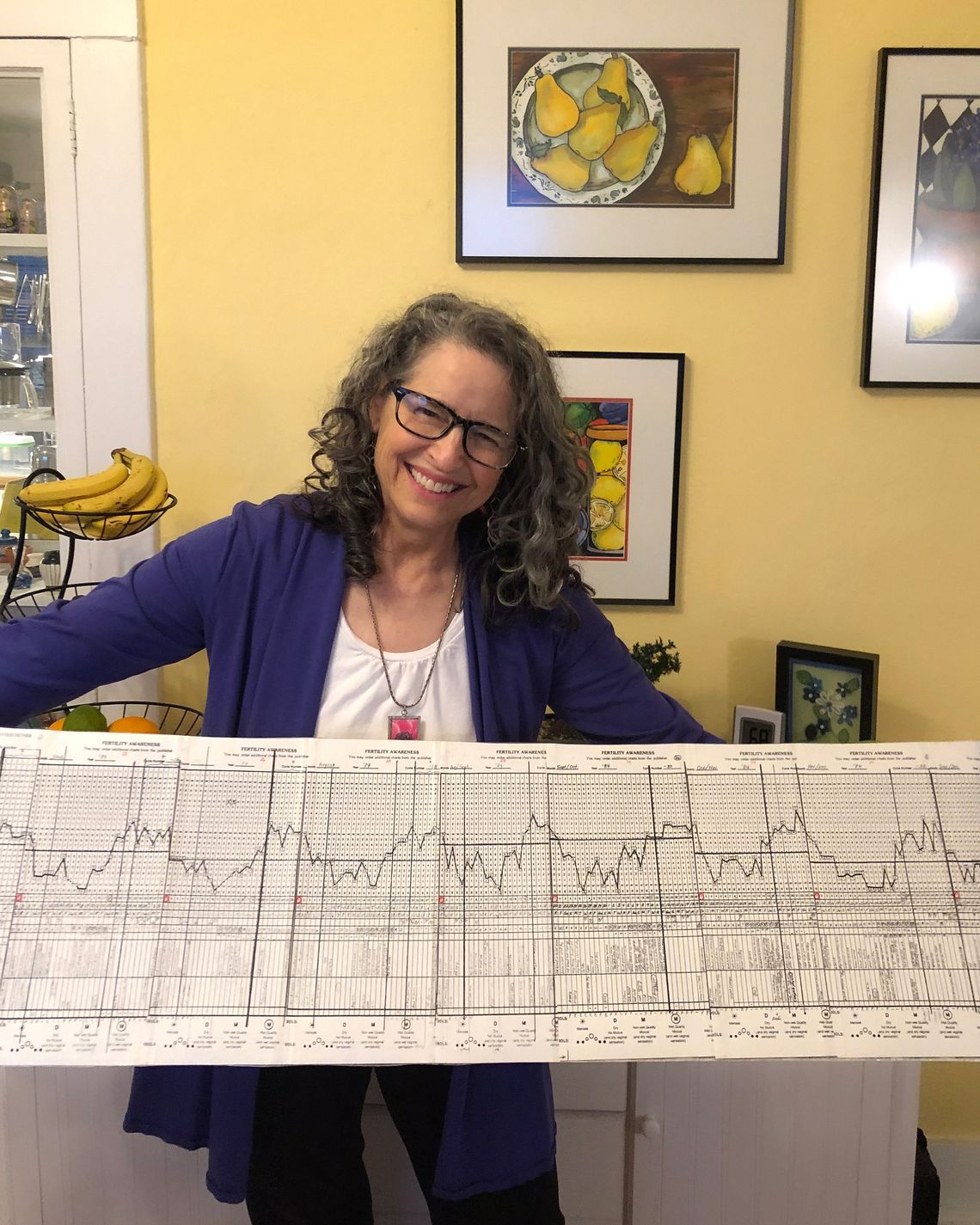

Through all of this, Weschler, now 68, has maintained a low profile. “I just want to be under the radar,” she tells me. It’s a rainy March day in Seattle, and she has planned our itinerary: coffee, a walk, a visit to her home. Her gray curls are tucked beneath a baby-blue kettle-brimmed hat; when we meet, she offers me a warmer jacket, mittens, and a hat of my own. She asks me not to reveal which neighborhood she lives in or to mention the coffee shop we visit. “I want women to know about FAM. I just wish it wasn’t with my name attached,” she says. She never imagined that giving women basic information about their bodies would become politicized in such a strange way, and she never intended for FAM to become a wholesale indictment of hormonal birth control. “I believe my book was the catalyst for getting this information out there,” she says. “The bad news is if you put this information in the wrong hands, it could be a disaster.”

These days, Weschler is at work on TCOYF’s fifth edition, which she swears will be the last. The process of updating and revising the book has always been a tremendous source of stress; every time, she is racked with fear that through negligence or poor writing or formatting, the book may lead to unwanted pregnancies. “Because women think of my book as the Bible, I feel like I can’t get anything wrong,” she says. She is so meticulous about where and how the example charts are placed that, years ago, one book designer working with her quit. A later edition was printed with an error that reversed her color-coded charts: In the birth-control section, the infertile days had been marked as the most fertile time and vice versa. When Weschler saw it, her stomach dropped. She called her agent and her editor, insisting the book couldn’t go out even though there were already stacks of books in warehouses ready to ship. The publishers printed inserts notifying readers that the colors had been reversed. She no longer trusts book designers, and, for this newest edition, she is attempting to build the entire thing herself on Microsoft Word.

As knowledge of FAM grows increasingly mainstream, the stakes and her sense of responsibility have only ratcheted higher — especially given the fact that there is no longer a federally protected right to an abortion. “I may ruin women’s lives,” she says. “Ironically, the very women whose lives I think I’ve changed.”

When the first hormonal-birth-control pill showed up in 1960, it was seen as the modern, feminist way to plan a family. In a 1962 Esquire article, a young Gloria Steinem describes the Pill ushering in a new era of “autonomous girls,” freed from the strictures of their biology to pursue whatever professional or sexual exploits they desired. In 1968, the anthropologist and writer Ashley Montagu likened the Pill to other feats of human ingenuity including tool-making, agriculture, and the control of nuclear energy. By 1969, controversies over the Pill’s safety and side effects began to swirl, but its popularity endured; by 1987, 80 percent of American women reported having used the Pill at some point, and in 1999 The Economist named the Pill “one of the seven wonders of the modern world.”

On the other hand, FAM, which originated as a contraceptive method promoted by the Catholic Church, developed a reputation for being unscientific and religious. The Church doesn’t allow couples to use barriers like condoms or hormones like the Pill. Instead, it promoted natural family planning, an umbrella term that includes FAM as well as a related tactic called the Rhythm Method, which requires women to count the days in their cycle rather than observe cervical fluid, the cervix position, and basal body temperature. The Church sees these methods as cheap, environmentally friendly alternatives to birth control that are good not only for reproductive health but also marital bonds. “NFP has the potential to make good marriages great!” enthuses the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops’ website.

Although FAM was largely practiced by Catholics, some health clinics, including Planned Parenthood, did offer classes. In 1982, Weschler walked into one of them. Growing up in L.A., the third of four children and the only girl, she had often felt like she couldn’t quite keep up. Her father, who died when she was 6, was a professor at UCLA. Her grandfather was the acclaimed avant-garde composer Ernst Toch. One brother was so ahead of his classmates he considered leaving for Yale at age 15; another brother, Lawrence, went on to become a journalist and writer at The New Yorker. “I felt like the village idiot,” she says. After college and a year on a kibbutz, she moved back home at 27 years old with the vague idea that she was interested in women’s health. Although she had inhaled her first copy of Our Bodies, Ourselves, Weschler was mostly clueless about her menstrual cycle. In college, she had regularly gone to the doctor, worried she had an infection because of the white fluid in her underwear.

She ended up getting certified to teach at the L.A. Regional Family Planning Council. There, she learned that her fluid was not only normal but could also reveal which hormones her body was producing, when she would next ovulate, and when she’d get her period. By then, she had already begun tracking her own cycle. Every morning, she recorded her temperature. Using the knuckles and tip of her middle finger, she’d measure her cervical openness and position and the quality of her cervical fluid. She’d write down if she was cramping or spotting, if her breasts felt tender. Weschler, who had color coded her calendar since high school, developed a color system for marking each sensation.

Learning to chart was like turning on a lightbulb. All of these sensations she had experienced weren’t dirty or wrong — they were part of a cycle with a logic she could understand and follow. Getting that information to more women became her life’s purpose. She earned her master’s in public health and began teaching her own classes in FAM, eventually settling into a Victorian house in Seattle. Weschler became part of a small network of secular women that wanted to bring FAM to a larger audience. Unlike their Catholic analogues, these instructors would teach anyone, from single women to unmarried couples. They would explain that in addition to charting, people could choose to use condoms or other kinds of contraceptives on days when they are fertile. “It’s about being pro-choice and about being pro-education,” says Michal Schonbrun, a member of the Association of Fertility Awareness Professionals, the professional organization for secular FAM educators.

Weschler remembers being the only Jewish person in rooms full of Catholics at natural-family-planning conferences in the 1980s and ’90s. “I went for the science,” she says. When the other conferencegoers learned she taught single women and unmarried couples, she was treated like a pariah. She lost contracts to teach FAM classes run by a Catholic organization because she was a single woman who spoke openly about sex out of wedlock. The secular world was hostile, too. When she taught training workshops to doctors and nurses, she was met with eye rolls. She scraped by, making $16,000 a year.

In those years, before the internet was widespread, the secular FAM network exchanged scientific research by making copies of studies and sending them in the mail. Each woman would receive the packet, copy the information, and then add her own resources and pass it on to the next person. Every year, they would meet up, cramming into hot attics with no air-conditioning or piling into a tiny New York apartment or a yurt in Alabama. They believed this kind of body literacy was a feminist act that gave women more control over their reproductive choices. They wanted to destigmatize menstruation, to help women feel less ashamed of their bodies.

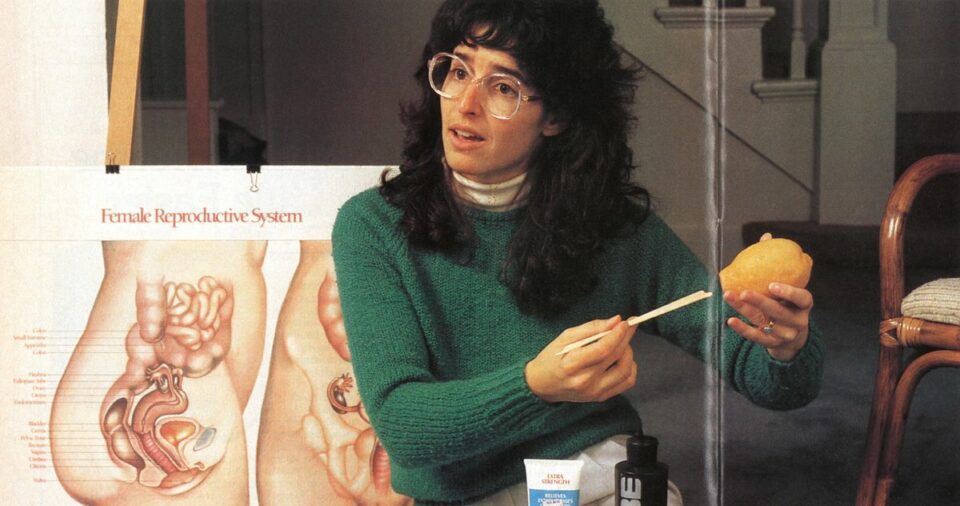

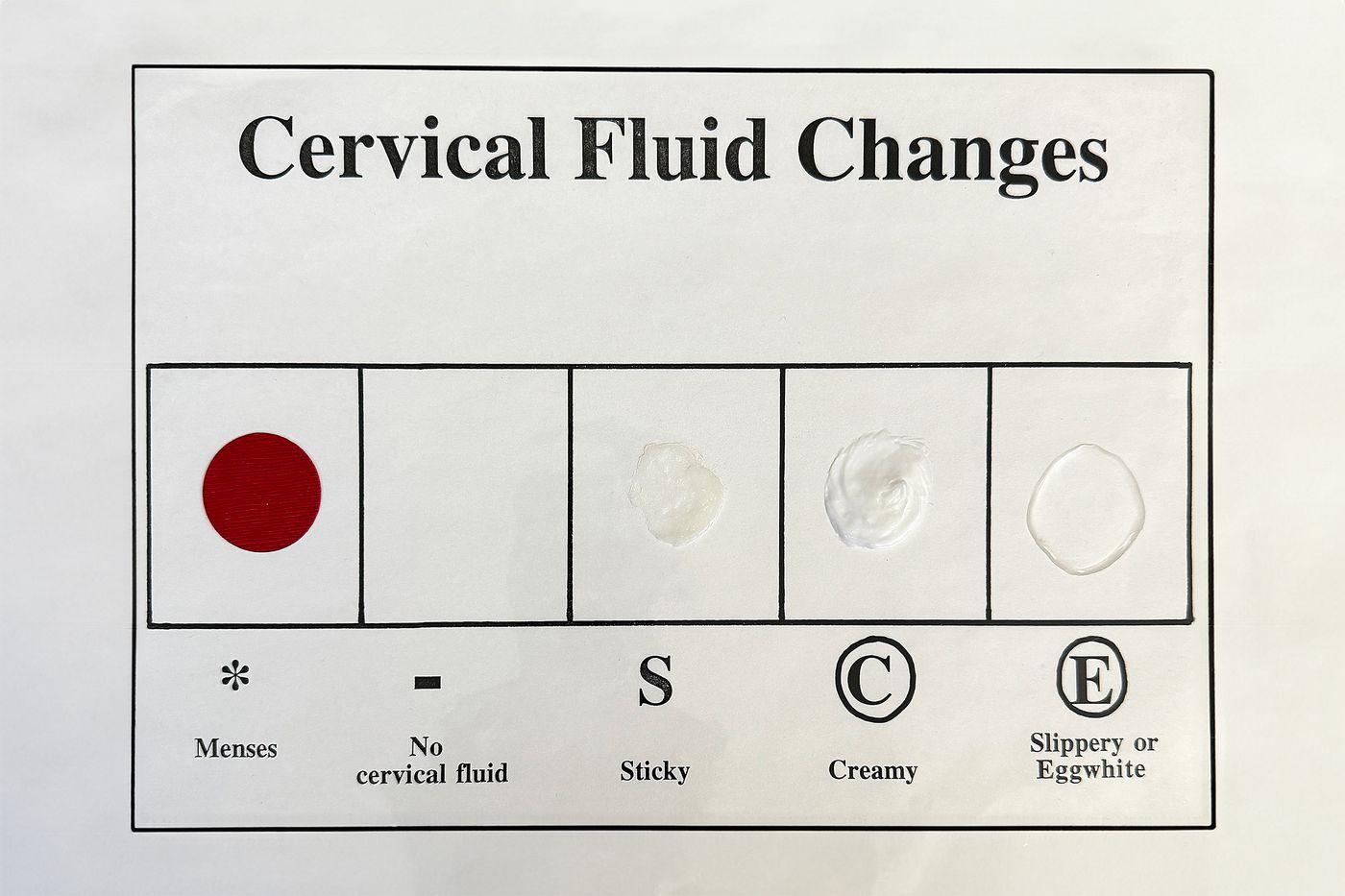

Weschler advertised in local papers and women’s clinics, but mostly people found her through word of mouth. During her classes, people would crowd into her living room, snacking on homemade apple cake and watching as Weschler cracked an egg, stretching the egg white to show how the release of the hormone estrogen would transform cervical fluid from a white gummy paste into a slippery, translucent liquid. She used a lemon to model how the uterus moves, and she’d unfurl 17 feet of her own laminated charts, using an ornately carved wooden yad to point to the low temperatures that precede ovulation. She encouraged men to participate in charting so they could understand and be equally responsible for their decision to have or not have children. Her students were a mix of couples and single people. Some were married and struggling to conceive, but most were trying to avoid pregnancy. There were chemists, teachers, people who worked in publishing or were professors at the University of Washington. Over and over again, Weschler found her female students were alternately thrilled to learn this information and furious. “I can’t believe that we were never taught this in school,” they would tell Weschler. “I can’t believe my mom never talked about this.”

Weschler decided the only way to reach women outside Seattle was to write a book. She roped in her younger brother Raymond as a co-author. Raymond had no interest in fertility — and was so sure he didn’t want kids that he’d gotten a vasectomy (he jokes that if he’d written the book, it would have been two words long: “Get clipped”) — but he was great at research and had access to the UC Berkeley library system. The two set out to re-create the experience of Weschler’s class in an accessible, thorough, well-researched book. It’s a process that, to this day, she describes as “absolute hell.” One problem was that TCOYF was trying to address two audiences with diametrically opposed goals: people who very much wanted to get pregnant and people who very much did not.

The effectiveness and risk of using FAM for these two groups are also strikingly different. If you’re interested in having a child, evidence suggests FAM can help you conceive faster and even help couples with fertility problems avoid having to use IVF. If you end up having sex on a non-fertile day, it’s not ideal, but it won’t cause a problem. But for women trying to avoid pregnancy, making a mistake could have serious consequences. Depending on the type of FAM you use — some FAM users monitor only their cervical fluid; others track their cycle lengths alongside their physical observations to predict ovulation — failure rates vary anywhere from 2 percent to 34 percent. What’s more, none of the studies on FAM’s effectiveness are high quality and “should be interpreted with caution,” according to Chelsea Polis, a reproductive-health epidemiologist at the think tank Population Council.

Another problem is that even if all women follow the same rules, not everyone will interpret their data correctly or abstain from sex on the days when they’re fertile. Almost all contraceptives rely on users to work properly — while the Pill is theoretically 99 percent effective, in the real world its failure rate is about 7 percent. That’s especially true for FAM because users are so involved in tracking and understanding these daily biomarkers. If you use a fertility-based method incorrectly, Polis says, by definition you’re having sex without contraception on a day when you’re likely to become pregnant. Even in scenarios where women use FAM perfectly, the failure rate can range from less than one percent to 12 percent. FAM is still a niche contraceptive and only about 3 percent of American women use it to prevent pregnancy, but that number has tripled since 2008.

Weschler successfully used FAM as a contraceptive for decades, but she also recognizes that it requires a lot of motivation, education, and precision to do right. “I am the first person to say that fertility awareness is not for everyone,” she says. To communicate this risk in TCOYF, she created two separate sections titled “Natural Birth Control” and “Pregnancy Achievement.” Each had detailed instructions along with sample charts from real women showing how women could manage different scenarios: how to know when it is safe to have sex after ovulation, how to identify if semen is masking as fertile cervical fluid. She included color-coded charts for each goal, highlighting fertile and infertile days, and wrote an appendix entitled “Natural Family Planning: Highly Effective, Highly Unforgiving” on the risks of using FAM as contraception. But those measures didn’t alleviate her fear that women would have unplanned pregnancies because the book was unclear. “I’m not legally responsible — I get that,” she says. “But that doesn’t mean that I wouldn’t feel sick about it.”

Weschler has since published three more editions, each including more and better information ranging from updated research on treatments for polycystic ovarian syndrome and endometriosis to an entirely new section about female orgasm. The process never seems to get any easier. “You would think by now I would’ve shot myself,” she says. Each time, her garden goes untended. Her carefully terraced vegetable plots lie fallow and her prodigious fig tree unharvested. Her friends won’t hear from her for months.

Weschler’s life has stayed relatively untouched. She lives in the same modest house where she taught FAM classes in the 1980s. Some of the other secular FAM women she has worked with have gone on to create a professional association and FAM-certification courses to train instructors, but Weschler was so preoccupied with TCOYF that she never created her own program or certification — something she now regrets. She lives on her book royalties, which she says amount to about $40,000 a year. In the past, she would respond to everyone who wrote to her with questions. Once, when a reader included her phone number, Weschler called her. They spoke for hours.

Weschler spent a long time debating whether to have children. She shows me flyers for her “Ambivalence About Motherhood” potlucks, which she hosted for several years in the early 1990s to discuss the ethics of “to have or have not.” Women were assigned to bring appetizers, entrées, or desserts depending on whether they were leaning toward having kids, not having them, or whether they were truly ambivalent. For Weschler, the choice to have children is something momentous and profound. “It is the only decision you’ll probably make in your life that’s irrevocable,” she says. After many potlucks and a lot of thought, Weschler ultimately decided not to do it. She loves them, but she says she’s squeamish and didn’t think she’d be able to adequately discipline her own. She’s a devoted aunt, writing cookbooks for her nephew and, for the past 14 years, taking her niece out every year to celebrate the day she got her first period.

In the past, she has tried to keep TCOYF politically neutral, though she always includes information about using it in combination with other barrier methods, and she prides herself on TCOYF’s scientific bona fides. But now, amid so much distrust of hormonal birth control and so many new restrictions on abortion access, she feels she can’t stay neutral anymore. The newest edition will, for the first time, include a section that explicitly mentions the Pill and explains that she supports any choice a woman makes about her reproductive health.

In her dining room, Weschler shows me her 31 years of charts: 377 of them, which she keeps in three-ring binders. Today, these charts function as a kind of diary of her life. Over time, she had begun to document the other things she felt in her body: every cold, headache, or pain in knee. She can see how the process of moving into her house — and how that stress, coupled with the demands of teaching and traveling — lengthened her cycle and delayed her ovulation that month. She can also see the ups and downs of her moods, until she stopped recording this in the mid-1990s when she realized that, while writing the book, she was always just depressed. “This was my body,” she says, tracing the rise and fall of her temperature and the rainbow of color-coded variables that made up each cycle.

Weschler stopped charting when she went through menopause, and it’s a ritual she mourns. For her, fertility awareness isn’t really about fertility at all. “It’s about allowing women to finally understand their bodies in a way that they couldn’t before,” she says. She sends me off with a hug and a packet of her favorite licorice-spice tea and later follows up with an email containing a list, labeled in red, of things she absolutely doesn’t want me to mention because “it just feels too revealing.” Then she signs off by telling me she has to get back to work. She had misplaced all but five of her chapters somewhere on her computer, and, once again, she’s starting to panic.

Related

- Do Weight-Loss Drugs Make Birth Control Less Effective?

[ad_2]

Sara Harrison , 2024-04-29 14:00:07

Source link