[ad_1]

This article was originally published November 24, 2020; it has been updated to include new series. HBO shows can be found here.

As HBO miniseries started developing in the mid-’80s and early ’90s, the “It’s Not TV. It’s HBO” tagline would not have applied. With a notable exception of Robert Altman and Garry Trudeau’s Tanner ’88, early efforts like The Far Pavilions and All the Rivers Run — the latter unavailable for us to include — had the scope of a typical two-night network event, with little of the ambition and artistry (and premium-cable pruriency) that would come to define the network. Even some of the more lauded, award-winning benchmarks from the mid-2000s, like the star-packed Richard Russo adaptation Empire Falls or the lavishly appointed historical drama Elizabeth I, hadn’t evolved past a more traditional model.

Yet there were occasional signs that HBO was ready to get some separation from other networks, both in terms of production values and complexity of storytelling. There was no other place, for example, that a miniseries like Band of Brothers could exist, given how closely it resembles the sweep and ground-level explicitness of a war film like Saving Private Ryan. The network also started breaking stories out of traditional boxes, so instead of the typical two-night miniseries event or a full series that might wear out its welcome, a series could simply last as long as it needed to. That influence is easy to spot in today’s TV landscape, where the limited series has become the preferred method of storytelling for plenty of networks, streaming services, creators, and top-tier actors.

For the most part, HBO miniseries have changed in step with its multi-season shows. (HBO original movies, on the other hand, are still lagging behind.) Prolific showrunners like David Simon have been able to toggle back and forth between formats, with the groundbreaking miniseries The Corner serving as a dry run for The Wire, and full stories like Show Me a Hero, The Plot Against America, and Generation Kill getting told in the space of six or seven episodes. The format has also been kind to the broad historical canvases of Band of Brothers, The Pacific, and John Adams; the intimate, personal storytelling of Mrs. Fletcher and I May Destroy You; and big statements like Watchmen and Angels in America. As usual, the hit-to-miss ratio is high: It doesn’t take more than a few bum titles to get to the good stuff here.

The Far Pavilions (1984)

For its first venture into the miniseries, HBO adapted M.M. Kaye’s best-selling doorstop of a novel into a five-hour-plus epic in the David Lean tradition, with few expenses spared in its $12 million budget, and with supporting players like Omar Sharif, Christopher Lee, and John Gielgud to bring the necessary gravitas. But the “It’s not TV. It’s HBO” slogan wouldn’t apply to The Far Pavilions, which feels like a clunky three-night network event — lavish but ill-paced and mercilessly abridged, with gobs of exposition to establish the historical context of the British Raj in the mid to late 1800s. Ben Cross stars as a man of conflicted allegiances to Britain and India, tested both in his service as a British cavalry officer and his star-crossed romance with an Indian princess (er … Amy Irving) who’s arranged to marry someone else. The flattening of this complex character into a colonial symbol carries over to the rest of the series.

The Casual Vacancy (2015)

Before Harry Potter’s creator J.K. Rowling started torpedoing fan goodwill with her public comments on gender, she’d begun making a move toward writing books for adults, starting with the small-town political dramedy The Casual Vacancy. Both the novel and the three-part BBC/HBO adaptation are about how a surprise parish council election exposes community secrets ranging from infidelity to drug addiction to rape. And both versions of the story suffer from some of the same deficits. In the TV Casual Vacancy, the serious topics clash with the thick-lined characters, and the low-key tone defuses any attempt to say something hard-hitting and true.

Tsunami: The Aftermath (2006)

The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami wiped out entire coastline communities in 14 countries, with fatalities estimated at over 225,000 people. For HBO and the BBC to come swooping in two years later with Tsunami: The Aftermath was a dodgy, “too soon” proposition that the two-part miniseries itself doesn’t do enough to allay. Set entirely in Thailand, the series takes the hoary form of a traditional star-packed disaster movie and centers familiar-looking Westerners, like Chiwetel Ejiofor and Sophie Okonedo as British parents searching for their missing daughter at a leveled resort, Tim Roth as a freewheeling journalist, and Toni Collette and Hugh Bonneville as a British consulate official and an Australian aid worker, respectively. Tsunami: The Aftermath does dig into the fecklessness and corruption of Western authority figures, but it nonetheless smacks of a tourist’s-eye view of a recent human tragedy.

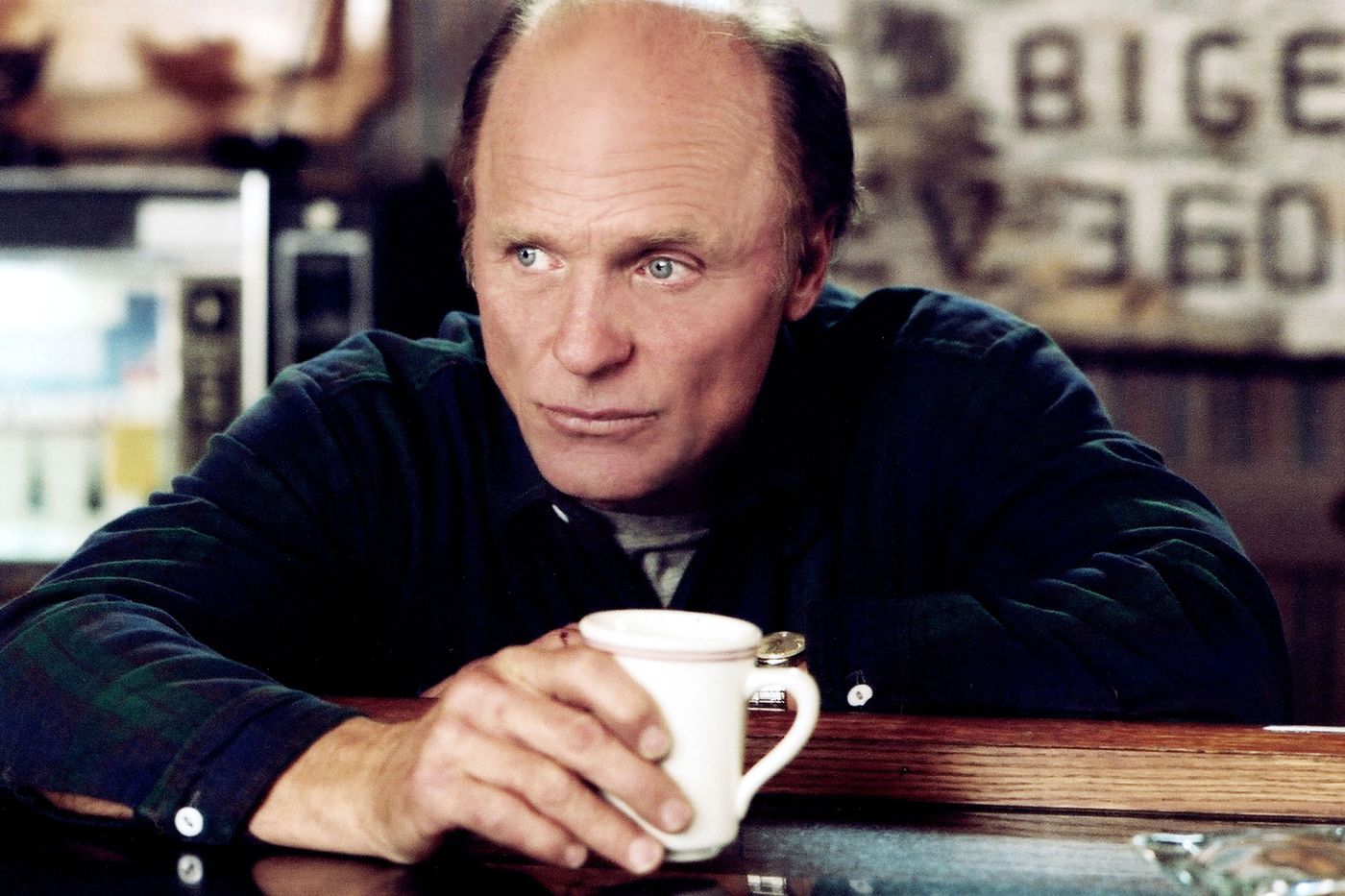

Empire Falls (2005)

Richard Russo’s beautiful novel about the inhabitants of a typical New England town in decline looks, on paper, like a best-case-scenario adaptation: Four hours to cover the book’s multigenerational sprawl without losing its gentle rhythms, a screenplay by Russo himself, and a loaded cast, including Ed Harris, Paul Newman, Helen Hunt, Philip Seymour Hoffman, and Aidan Quinn. Yet Empire Falls translates into a lumpen, stodgy miniseries, despite a fine central performance from Harris as a divorced diner owner with deep roots in the town and a structure that allows the past to keep informing and enriching the present. Translating Russo’s modest epic into a compelling miniseries was never going to be easy, even with the author himself taking a hand, but an air of complacency hangs over the series, which makes it jarring when a Columbine-like incident awkwardly shakes it from its stupor.

I Know This Much Is True (2020)

Mark Ruffalo gives his all to two roles in writer-director Derek Cianfrance’s adaptation of Wally Lamb’s melancholy, literary, epic-length best-selling novel. Ruffalo plays both a trouble-plagued working-class New Englander and his mentally ill twin brother, in a story that sees the two men learning hard truths about each other and about their own pasts, in the wake of violent incidents in the world at large and in their own lives. The miniseries is artful and thoughtful, with striking sequences throughout. It’s also fairly excruciating to watch. The somber tone and the nearly unrelenting misery makes it a challenge to stick with I Know This Much Is True for the full six-episode run … though for those who can manage it, the payoff is rewarding.

The Baby (2022)

This bizarre, bloated British horror-comedy aims to expose how having a child can be a physical and psychological ordeal, leaving parents feeling as if they’ve transformed into entirely new people. Michelle de Swarte plays Natasha, a single, childless, and child-averse 38-year-old who one day has a baby literally drop into her arms. Soon she finds she’s stuck with this kid who takes up her time and messes up her plans — and who, by the way, may be a demon responsible for a string of mysterious fatal accidents. Created by Lucy Gaymer and Siân Robins-Grace, The Baby has some memorable moments of humorously deadpan surrealism, though, like a lot of modern miniseries, it should probably have been a 90-minute indie movie and not an eight-episode, three-hour TV event.

Five Days (2007)

Produced in collaboration with the BBC, Five Days poses a clever approach to the standard-issue abduction narrative: Each episode covers one day in the case, but those days are not consecutive. (The five days are 1, 3, 28, 33, and 79.) The concept creates a storytelling dissonance, because viewers are invited to guess what happened in the days between and track the evolutionary leaps in both the investigation and the emotional states of the key players. The show opens with a mother and her two young children disappearing along the highway, which leads the detectives (Hugh Bonneville and a great Janet McTeer) to suspect her volatile husband (David Oyelowo) and an engaged tabloid press corps to follow suit. After a promising start, Five Days gets hung up in a Crash-like interweaving of events that sacrifices its character-based approach for narrative syncopation.

Catherine the Great (2019)

The lily is extremely gilded in this opulent four-episode miniseries, which brings Helen Mirren in full Dame Helen Mirren mode, back together with Nigel Williams, her writer on Elizabeth I. Catherine the Great opens shortly after the Russian empress (Mirren) seized the throne from her husband, as she immediately faces challenges to her legitimacy from several traitors, including her own feckless failson. Though the series traces her political evolution — from her modernization of Russia to her retreat on reforming serfdom — it’s mostly a decorous and lusty bodice-buster, focusing on Catherine’s May-December fling with Grigory Potemkin (Jason Clarke) and other bedroom intrigue, broken up by the occasional smiting of enemies. It’s diverting, but exactly the sort of costume piece that seemed destined to score Mirren a Golden Globe nomination and be forgotten about … which is exactly what happened.

Elizabeth I (2005)

Taking home seemingly every award for which it was eligible, the two-part miniseries Elizabeth I was a standard-setting prestige event for the network, with Helen Mirren anchoring a cast that includes Jeremy Irons as the earl of Leicester and Hugh Dancy as the earl of Essex, with future Oscar winner Tom Hooper directing. Tartly scripted by Nigel Williams, the series is a gloss on the political and personal upheaval that defined the consequential latter half of Elizabeth I’s reign, when she and her Protestant kingdom were beset by Catholic rivals, assassins, and other challenges to the throne. Elizabeth I dutifully and decorously re-creates a period where politics and religion mingled. Mirren’s performance adds some complexity; her queen is shrewd and ruthless at times, vulnerable and enigmatic at others. The fullness of the character redeems the series.

Parade’s End (2013)

The playwright Tom Stoppard returned to television to write all five episodes of this adaptation of Ford Madox Ford’s novels, and his dry wit is evident in the tale of an aristocratic cuckold whose life is upended by events in and around World War I. With an upper lip stiffer than a meringue peak, Benedict Cumberbatch stars as the well-heeled conservative son of a Yorkshire lord, who falls first into a quickie marriage with a promiscuous and pregnant socialite (Rebecca Hall), who has contempt for him and motherhood. He then takes an unlikely romantic interest in a free-spirited suffragette (Adelaide Clemens). Cumberbatch’s performance is like witnessing the class system succumb like the slow crack of a glacier; but Hall dominates the series by delivering the lion’s share of Stoppard’s withering one-liners and adding redemptive notes to a character who isn’t as thoughtlessly cruel as she seems.

House of Saddam (2008)

A year after The Sopranos ended, this four-part miniseries gave Saddam Hussein the Tony Soprano treatment, making him the charismatic thug at the center of a political rise-and-fall that plays out like a nonfiction mafia drama. Starting with the freeze-frame, record-scratch moment of Hussein (Igal Naor) and his family watching George W. Bush announce his intentions to invade Iraq and liberate its people, the series then flashes back to the aftermath of the Iranian Revolution in 1979 and follows Saddam’s tyrannical ascent. It’s a fruitful idea for a miniseries, to consider an authoritarian as it might a gangster; and it’s a perspective on world historical events that American viewers rarely got to see. But as a historical soap opera, House of Saddam isn’t quite as arresting as it needs to be, even as it documents the gruesome consequences of one man’s paranoia, megalomania, and self-destructive hubris.

The Undoing (2020)

Big Little Lies writer-producer David E. Kelley mines some of the same territory in The Undoing, a six-part adaptation of Jean Hanff Korelitz’s novel You Should Have Known. Nicole Kidman and Hugh Grant play a seemingly happy and fabulously wealthy New York couple whose lives are upended when the husband is accused of murdering his mistress. Kelley has a knack for parceling out game-changing plot twists, such that, all the way up until this miniseries’ final episode, it’s possible anyone could be the killer. And he gives his actors a lot to play with, as their characters sort through one another’s secrets and lies. (Grant, for one, gives one of the better performances of his career, playing an affable gent with a disturbing dark side.) But unlike Big Little Lies, there’s an unrelenting dourness to The Undoing, which make its trashy sex scandals and murder mysteries less of a guilty pleasure and more of a chore.

Years and Years (2019)

At times too painfully real to enjoy, this dystopian science-fiction miniseries — created by Doctor Who and Queer As Folk writer-producer Russell T. Davies — begins with the present-day election of a populist demagogue and then moves ahead to the near future to show how one ordinary British family is torn apart by a rapidly changing nation. Emma Thompson gives an alternately creepy and charismatic turn as the politician. Her character drives the action, but Years and Years is more about how citizens do their best to endure even as society collapses all around them. It’s less a “what if” than a “how to.”

The Outsider (2020)

Adapted from Stephen King’s novel by Richard Price, the brilliant novelist and TV writer on shows like The Wire and The Night Of, The Outsider initially seems like a dark police procedural, with a small-town detective (Ben Mendelsohn) investigating a boy’s murder and concluding that his Little League coach was the culprit. But then it becomes a Stephen King story, introducing a supernatural threat that forces everyone to think beyond the possible or suffer the consequences. The series mixes the everyday with the inexplicable beautifully, with a standout performance by Cynthia Erivo as an eccentric private eye. But it loses some of its grip in the final episodes, which suffer from King’s typical third-act chaos. (Nevertheless, a proposed second season could shift The Outsider from being a miniseries to regular series, though it would need to clean up a small mess first.)

Gunpowder (2017)

Aired after the seventh season of Game of Thrones, this tight three-part miniseries about the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 seemed intended to slake any remaining thirst for period bloodletting and outsize acts of revenge. As Robert Catesby — the leader of a group of English Catholics who intended to assassinate the Protestant King James I — Kit Harington is much more resolute than as Jon Snow, his Game of Thrones hero. But the two characters share a sense of righteous justice, along with a willingness to follow that impulse through to the bloody end. Though Guy Fawkes remains the most significant cultural remnant of the failed plot, Gunpowder keeps the focus on Catesby as the chief instigator and gets a particularly nuanced performance out of Peter Mullan as Henry Garnet, a Jesuit priest torn between his distaste for violent rebellion and his belief in the sanctity of the confessional. The show has the familiar look of BBC/HBO historical drama, but the story requires an escalating sense of urgency, and danger keeps it lively, especially in the dread-filled finale.

Laetitia (2021)

The acclaimed true-crime documentarian Jean-Xavier de Lestrade (best known for the Oscar-winning Murder on a Sunday Morning and the international hit docuseries The Staircase) shifts to a lightly fictionalized version of a real-life murder case in Laetitia, which uses the shocking disappearance of a teenager as a way to explore deeper social ills in France. Co-written by de Lestrade and Antoine Lacomblez, the series jumps back and forth through time and weaves among characters, stopping to study the killer, the victim, her twin sister, and various well-meaning but underfunded officers of the criminal-justice system. The series is sometimes muted to a fault; but, for the patient viewer, it offers a thoughtful, human-scaled look at a world where sometimes violence goes unpunished.

White House Plumbers (2023)

The exploits of “the Plumbers,” a name given to a covert Special Investigations Unit designed to plug up leaks in Richard Nixon’s White House, seem like ideal fodder for political comedy, particularly given the Keystone Cops–level ineptitude that defined the group well before they bungled the Watergate break-in. But White House Plumbers is a curious misfire, despite a loaded cast led by Woody Harrelson and Justin Theroux as far-right mischief-makers E. Howard Hunt and G. Gordon Liddy, and direction by David Mandel, who served as showrunner for HBO’s Veep after the first season. There’s some fun to be had watching these wildly paranoid and overconfident buddies whiff on a million-dollar dirty-tricks operation, but the show veers too far into the cartoonish. The facts are funny enough on their own.

Beartown (2021)

Based on a Fredrik Backman novel, this five-part Swedish series is set in a hardscrabble small town that prides itself on producing championship-caliber junior hockey teams. When a sexual assault threatens to wreck the local squad’s season, the community turns against the victim and anyone who supports her. It’s a story that’s all too common regardless of the country or culture. Beartown is an undeniably grim series, unsparing in its explorations of selfishness, small-mindedness and privilege. But it’s also an effective sports drama, which allows audiences to experience the highs and lows of life on the rink — to understand why these games matter so much to so many.

Mrs. Fletcher (2019)

Based on Tom Perrotta’s novel — with the author himself serving as showrunner — Mrs. Fletcher is more in line with the deft observational comedy of his books The Wishbones and The Abstinence Teacher than more serious-minded efforts like The Leftovers or Little Children (though it’s not without its provocations). Mostly, it’s a fine vehicle for Kathryn Hahn, a middle-aged divorcée who sees her entitled, ungrateful son (Jackson White) off to college and starts to experience a sexual renaissance, fueled by a strange obsession with pornography. The pleasures of the show are modest and ever-so-slightly imbalanced. (Hahn’s erotic misadventures are more compelling than her son’s humbling adjustment to young adulthood.) But Perrotta has a fine sense of proportionality and a keen eye for comic detail.

The Regime (2024)

Creator Will Tracy, a writer on Succession who also co-scripted The Menu, brings a similarly nasty edge to this satire about a central European autocracy on the brink, starring Kate Winslet as an imperious dictator who gets involved with a violent, emotionally unstable soldier (Matthias Schoenaerts) she brings into her inner circle. The Regime cruises for a few episodes as a passable facsimile of an Armando Iannucci series like The Thick of It or Veep, buzzing on a viper’s nest of palace intrigue and a keen sense of how autocracies convert populism and propaganda into piles of dirty money. But when it shifts into a more conventional political thriller toward the end, the thinness of its characters and conceit gets exposed.

Our Boys (2019)

In the summer of 2014, Hamas militants kidnapped and killed three Jewish teenagers. Two days later, a Palestinian teenager named Mohammed Abu Khdeir was found burned to death in the woods outside Jerusalem, clearly a retaliatory act. It takes tremendous sensitivity and skill to make a ten-episode series around these events — indeed, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu called for a boycott when it aired on Israeli television — but Our Boys takes a careful, scrupulous approach to the material, sticking closely to the Shin Bet terrorism agent investigating Mohammed’s murder and to the boy’s grief-stricken family as they search for justice. In the middle of these acts of extreme violence, the series has a prevailing compassion for characters on both sides of the Israeli-Palestinian divide, and emphasizes the tragic cycle of violence that subsumes even blameless young people.

Mosaic (2018)

Like his previous digital projects for HBO, K Street and Unscripted, Steven Soderbergh’s murder mystery was an opportunity for the director to experiment in new technology and new modes of storytelling. Mosaic existed as a mobile app first, in late 2017, allowing viewers to find their own way through the story of a famous children’s book author (Sharon Stone) who’s found murdered on New Year’s Eve, with a con man (Frederick Weller) and a boarder (Garrett Hedlund) as the chief suspects. The mixed-media conceit may explain why the pacing is so slack for a six-episode series. (The inciting incident doesn’t even happen until halfway through the second episode.) But the extra time spent on characterization does pay off in sorting through the complicated motives of everyone involved. It’s not exactly a revolution in miniseries form, but once the pieces are in place, the mystery is deftly handled.

Scenes From a Marriage (2021)

The 1973 Ingmar Bergman miniseries Scenes From a Marriage chronicled the dissolution of a relationship with a sustained intensity that was familiar to audiences for his films but unusual for television. This English-language remake may not be so revolutionary, but over five episodes, it certainly doesn’t lack for dramatic intensity, as Mira (Jessica Chastain), a world-traveling tech executive, and her academic husband, Jonathan (Oscar Isaac), start to pull away from each other. Each episode begins with one of the lead actors heading onto a COVID-protected set to do their scene, but even that bit of stagecraft gives little relief to Mira and Jonathan’s painful shouting matches and microaggressions, which occasionally give way to old feelings. It’s raw, real, and a little bit exhausting, but Chastain and Isaac have persuasive chemistry even in the low moments.

The Investigation (2021)

The Danish writer-director Tobias Lindholm (best known for A Hijacking and The Good Nurse) takes an unusual approach to true crime in this haunting six-part series. Although ostensibly about what happened after Swedish journalist Kim Wall’s dismembered corpse was found strewn across Køge Bay in 2017, The Investigation doesn’t dwell much on the sensationalistic murder itself. Instead, Lindholm follows two cops (played by Soren Malling and Pilou Asbaek) as they piece together the gruesome clues, sacrificing their personal lives to follow the trail of the eccentric entrepreneur who is their prime suspect. This is a sophisticated procedural, detailing how the time and effort it takes to build a case can be a burden on everyone involved — from the detectives to the victim’s family.

Landscapers (2021)

Olivia Colman and David Thewlis star in this quasi-true crime story as Susan and Christopher Edwards, a real-life married couple who shared a disturbing secret: They had killed Susan’s parents and had been living for years off their pension checks while the corpses rotted in the backyard. Landscapers’ writer Ed Sinclair and director Will Sharpe inject some arty style into this eerie tale, pivoting off their lumpen anti-heroes’ love of movies to at times make them look like characters in a big-screen melodrama. What results is a kind of cockeyed mystery not at all about whodunnit but about why these two lovers felt compelled to resort to violence and lies.

The Third Day (2020)

This deliberately paced and dreamy drama is aimed at fans of films like The Wicker Man and Midsommar… or really any horror/fantasy story in which troubled souls stumble onto eerie cults in remote locales. Jude Law plays a harried businessman with a complicated home life, who ends up stuck in a small island village which gets cut off from civilization whenever the tide rises. There he meets another outsider (played by Katherine Waterston), who explains the odd rituals and the unique social order of these rural Englishfolk — all while harboring some secrets of her own. The Third Day often favors spooky ambiguity over strong emotional engagement; but the acting and atmosphere are outstanding, and like the movies it’s aping, it has an enjoyably twisty plot, which takes some jarring turns.

Sharp Objects (2018)

Based on the novel by Gillian Flynn (Gone Girl), who also had a hand on a few of the scripts, this eight-episode psychological thriller turns its title into a full-on aesthetic, with a rapid deployment of flashbacks that keep stabbing away at the present. Amy Adams is superb as a Kansas City crime reporter who’s asked to return to her hometown of Wind Gap, Missouri, to investigate the murder of two young girls — an assignment that forces her to confront her own traumatic past in Wind Gap as well as her broken relationship with her socialite mother (Patricia Clarkson). It takes time to settle into creator Marti Noxon and director Jean-Marc Vallée’s jagged conceit, which is light on suspense and heavy on southern-gothic atmosphere and time-is-a-flat-circle chronology. But it burrows deep into the conscience of a woman who returns to a terrible place her mind never left.

We Are Who We Are (2020)

For his television debut, co-creator and director Luca Guadagnino accesses the same adolescent feelings of uncertainty and possibility that underscored his 2017 coming-of-age film Call Me By Your Name. It’s a cliché to talk about the setting as a character, but setting and character dovetail perfectly on American military base in seaside Italy, where Fraser (Jack Dylan Grazer) and Caitlin (Jordan Kristine Seamón) try to sort out their ambiguous identities in an environment that bends toward conformity. They aren’t as compelling as they should be — as their plainspoken, sexually adventurous friend, Francesca Scorsese, daughter of Martin, steals a lot of scenes — but the sensual kick of the music and Guadagnino’s direction carries the series along.

Laurel Avenue (1993)

It’s too bad that Laurel Avenue couldn’t be remade today, with much of the same creative team, but with a look and tone closer to modern prestige television. Directed by Carl Franklin (between his twin masterpieces One False Move and Devil in a Blue Dress) and co-written by producer Paul Aaron and playwright Michael Henry Brown (with input from producer Charles S. Dutton), this two-part, nearly three-hour melodrama follows an eclectic, multigenerational St. Paul, Minnesota, African American family over the course of a few days, as a lot of their personal dramas and conflicts come to a head. The writing, performances, and direction are all outstanding, even if the tone and style are a bit too blunt. Laurel Avenue arrived in an era when the issues brought up in the story — drugs, interracial relationships, institutional racism — were typically framed on television as “Issues” with a capital I. Yet even with those expectations weighing it down, this miniseries frequently soars, featuring bracing conversations about class and culture that even today are rare to hear on television.

We Own This City (2022)

Working from a nonfiction book by reporter Justin Fenton, creators David Simon and George Pelecanos return to the dysfunctional Baltimore of The Wire and The Corner but with a stronger emphasis on the institutional rot within the city’s police department and the citizens who suffer as a result. Jon Bernthal brings every bit of his dark charisma to bear as Sergeant Wayne Jenkins, head of the Gun Trace Task Force, a free-roving elite unit that prides itself on splashy busts but mostly engages in violent shakedowns and brazen robberies. As with Simon’s best series, We Own This City details how corruption isn’t limited to a few bad actors but moves through the entire system like a metastasizing cancer.

The Pacific (2010)

This companion piece to the acclaimed, award-winning Band of Brothers brings back a lot of the same behind-the-camera creative team to tell the story of some of the bloodiest campaigns of WWII’s “Pacific theater,” from the perspective of multiple U.S. Marines: a moody war hero (Jon Seda), a shell-shocked romantic (James Badge Dale), and a sensitive youngster (Joseph Mazzello). The war against Japan was very different from the war against Germany in myriad ways, and The Pacific doesn’t shy away from the complexities of a cause that was sometimes hazier and less inspiring to the men and women who fought for it; nor does it shortchange either their brutality or their humanity.

Irma Vep (2022)

Back in 1996, writer-director Olivier Assayas made the ultracool cult favorite Irma Vep as a critique of a French film industry that was chaotic and creatively moribund with Maggie Cheung playing a version of herself stranded in a remake of silent serial called Les Vampires. With this elegant, lightly satirical series, Assayas again surveys the filmmaking landscape, but now auteurs and stars are turning to television, which has pitfalls of its own. Alicia Vikander does fine work as an omnisexual Hollywood star who retreats to Les Vampires partly to hide from the tabloids, but it’s Vincent Macaigne who steals the show as a director so notoriously volatile that the production has trouble even getting insured.

The Night Of (2016)

Reconceived from the first season of the British series Criminal Justice, Richard Price and Steven Zaillian’s twisty eight-part miniseries starts as what seems to be a “wrong man” story about a Pakistani-American college student (Riz Ahmed) from Queens who’s accused of murdering a young woman. Though the case seems open-and-shut to the lead detective (Bill Camp), the show initially aligns itself closely with the alleged perpetrator and his lawyer (John Turturro), only to raise troubling questions later. The Night Of uses the pulpy procedural format to explore the grim realities of the justice system, the class and racial fault lines that divide New York City, and the way such incidents can play out in the press and in the court of public opinion. Beyond the “did he or didn’t he” mystery, the series lays out the experience of a suspect in rich, comprehensive detail.

The Corner (2000)

Based on The Corner: A Year in the Life of an Inner-City Neighborhood, their book about the poor and drug-infested hub of Fayette Street and Monroe Street in West Baltimore, David Simon and Ed Burns’s groundbreaking series is considered a rough draft for The Wire, which Simon, Burns, and several cast members would start making two years later. But while the shows share an aesthetic and thematic DNA, The Corner has a slice-of-life quality that’s more in line with a later Simon series, like Treme, and a documentary realism that’s entirely its own, with director Charles S. Dutton occasionally feeding the characters questions offscreen. It also has a heartbreaking center in Gary McCullough (T.K. Carter), a softhearted heroin addict whose personal decline mirrors the diminishment of his once-thriving neighborhood.

Show Me a Hero (2015)

It’s hard to overstate the prescience of writer-producer David Simon’s Show Me a Hero — co-written with William F. Zorzi and directed by Paul Haggis, and adapted from a Lisa Belkin nonfiction book. Oscar Isaac stars as real-life politician Nick Wasicsko, who in 1987 became the mayor of Yonkers at age 28, right when the New York town was hit with a court order demanding the city provide affordable housing to locals regardless of race. This miniseries is uncommonly wise about the frustrating tentativeness of our leaders and the fearful bigotry of our neighbors; but it’s also about how change comes regardless of the stubbornness of the resistance.

The Plot Against America (2020)

The third straight David Simon miniseries on this list is an unusual project for him: an adaptation of Philip Roth’s alternate-history novel that downplays the fantastical “what if”s of the book and instead aims to be more of a muted, nuanced piece of American anthropology, akin to The Deuce and Treme. The premise is wild: Imagine the U.S. in the early 1940s if the fascist-sympathizing aviation hero Charles Lindbergh beat FDR and became president. But the presentation draws more from the parts of Roth’s The Plot Against America that examined how it felt to be Jewish in New Jersey while the Nazis were on the rise. A great cast is led by Morgan Spector and the magnificent Zoe Kazan, playing middle-class parents who suddenly realize that their position in their own native country — along with what they’ve built for their children — is subject to terms and conditions by the gentile majority.

Band of Brothers (2001)

Originally released right around the time of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the Tom Hanks/Steven Spielberg–produced World War II miniseries Band of Brothers served as a curious kind of comfort viewing back in 2001: a traditional “men on a mission” battlefield saga featuring an assortment of complicated but ultimately honorable American soldiers. The series didn’t ignore the effects of nonstop combat on the hearts, minds, and bodies of these men, some of whom had to deal with PTSD, substance abuse, and a creeping cynicism. But those darker elements — combined with the stellar performances of a top-shelf cast, led by Damian Lewis and Ron Livingston — only enhances the narrative sweep and emotional swells of a story that ranges from basic training to a climactic assault on Hitler’s “Eagle’s Nest.”

From the Earth to the Moon (1998)

One of HBO’s first blockbuster events, this Tom Hanks–produced miniseries breaks the history of NASA’s lunar exploration into a dozen short stories, presented in a variety of styles, with a different focus (and often a different main cast) for each episode. Sometimes From the Earth to the Moon functions like a procedural, detailing the particulars of how scientists, bureaucrats, and pilots came together to do something astonishing. Sometimes it’s like a mosaic, considering the Apollo missions from the perspective of those hovering around the fray, like the wives or the press. The result is an educational and exciting drama — as dogged and daring as NASA itself.

John Adams (2008)

A few years before the Broadway musical Hamilton (a show that takes more than a few potshots at America’s second president), John Adams brought the United States’ early history to life, depicting the complicated interpersonal relationships of the men and women who forged a new nation. Director Tom Hooper and screenwriter Kirk Ellis (adapting a David McCullough biography) make the Founding Fathers and Mothers seem likably human, while setting them against a past that looks alien. The key to the miniseries is the chemistry between the two leads: Paul Giamatti, as a crankily traditionalist yet still idealistic Adams, and Laura Linney, as his opinionated, oft-abandoned wife, Abigail. The couple’s lifelong romance — enduring through brutal political campaigning and family strife — grounds this story.

Mare of Easttown (2021)

This evocative seven-episode crime drama, set in a small community outside of Philly that’s both close knit and rife with dark undercurrents, was a rare achievement on two fronts: (1) It was a genuine water-cooler event at a time when television audiences are scattered across multiple channels and platforms; (2) it’s a whodunit that’s extremely challenging to solve but doesn’t feel like a cheat in the end. Beyond that, Mare of Easttown has a terrific anchor in Kate Winslet, who disappears into the role of a detective sergeant who tries to investigate a young woman’s murder but is undermined by critical mistakes and her own potential connection to the case.

I May Destroy You (2020)

Part mystery, part slice-of-life, part eye-opening psychodrama, I May Destroy You tells a story about sexual assault while considering more than just the incident itself or its immediate aftermath. Written by and starring Michaela Coel (who also co-directed several episodes with Sam Miller), the series follows a famous London-based writer, known for her libertine lifestyle and her hot takes on millennial culture. When she blacks out during a night of partying, she begins investigating both what actually happened to her and what it means to her self-image as a gregarious free spirit. Throughout, Coel documents her generation of young Brits, while describing in vivid detail how a single moment of violence can cause lingering pain.

Olive Kitteridge (2014)

Frances McDormand gives a complex, challenging, and Emmy-winning performance in this adaptation of an Elizabeth Strout novel, about a persnickety New England schoolteacher who can’t help but push away the people she loves. Director Lisa Cholodenko and screenwriter Jane Anderson follow Strout’s lead and break Olive’s story into a series of short, literary vignettes, which illuminate the heroine’s relationships and her worldview — and which are each like highly entertaining short films. Over time, Olive’s cartoonish snarl gives way — movingly — to a deeper humanity, as she begins to own up to her mistakes and her regrets.

Watchmen (2019)

There are so many ways Damon Lindelof’s audacious riff on Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’s graphic novel could have gone wrong that every episode of Watchmen feels like a gamble. But it unfolded with the confidence and vision to support its provocations. Remnants of previous Lindelof shows like Lost and The Leftovers are present in its puzzle-box revelations and obsession with lingering societal trauma; but Watchmen has its own agenda, updating the book’s ’80s-specific interest in the Cold War and nuclear annihilation to present-day issues of racism and white supremacy. Yet for such a heavy show, Watchmen doesn’t skimp on the pulpy pleasures of an adult-oriented comic, with plenty of kick-ass action sequences and a soundtrack that mixes a Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross score with choice songs from multiple eras. In the future, no one will believe that a show about Black oppression past and present, populated by characters in masks, was produced before the COVID-19 outbreak and Black Lives Matters protests overwhelmed the culture.

Generation Kill (2008)

Based on a book by Rolling Stone reporter Evan Wright — who co-created the show and is played onscreen by Lee Tergesen — Generation Kill is one of the definitive works about the Iraq War, following the Marine Corps’ 1st Reconnaissance Battalion from the Kuwait-Iraq border all the way into Baghdad. This was when the war was a success: the first “shock and awe” blitz that would trigger more lasting instability and violence. But The Wire’s David Simon and Ed Burns carefully plant signs of the failures to come. Simon and Burns’s grunt’s-eye view of the war is basically The Wire in the desert, an institutional cataclysm where poor decisions at the top of the military food chain trickle down to men on the ground.

Mildred Pierce (2011)

The 1945 movie adaptation of James M. Cain’s novel — starring Joan Crawford — condensed the material into a film noir. Todd Haynes’s expansive five-episode miniseries is a florid, beautifully realized melodrama in line with “women’s weepies” like Stella Dallas or Haynes’s own Douglas Sirk throwback Far From Heaven. Kate Winslet is superb as an overtaxed mother during the Great Depression who tries to open a restaurant and sort through a difficult love life while sacrificing everything for a daughter (played as an adult by Evan Rachel Wood) who treats her horribly. Haynes respects the emotional intensity of the genre while sumptuously re-creating the period. As his Mildred hustles industriously to stay afloat, she bucks up against the humbling austerity of the times.

Chernobyl (2019)

When pop-culture history is written, no one will believe that Chernobyl was aired before the coronavirus outbreak, so keenly does it speak to a tragedy metastasized by institutional arrogance, incompetence, and lies, and a failure to prioritize human health over authoritarian ego. Over five absolutely riveting episodes, the series covers the ticktock of a core explosion at the nuclear power plant in Chernobyl in April 1986 — and then follows the politically sensitive effort to contain the damage and inform the public. Jared Harris and Stellan Skarsgård are an excellent team as an intrepid scientist and a party chairman, who throw themselves into a perilous situation in every respect; and Emily Watson does fine supporting work as a nuclear physicist who pressures them to do the right and difficult thing.

Tanner ’88 (1988)

A daring experiment in political satire — unlike anything that’s been on TV before or since — Tanner ’88 ran new episodes once a month in the spring and summer of 1988, shadowing the real-life Democratic presidential primaries. Michael Murphy plays a genial but wishy-washy Michigan congressman (with future HBO star Cynthia Nixon as his idealistic daughter), in a show that had actors interacting with actual politicians, all of whom were struggling to define themselves in the media toward the end of the personality-driven Reagan era. Doonesbury cartoonist Garry Trudeau and counterculture filmmaking hero Robert Altman collaborated on the miniseries, reacting to unfolding events with an eye toward both their absurdity and their humanity. Their innovative hybrid of documentary and fiction established a template for everything from Christopher Guest–style mockumentaries to ripped-from-the-headlines comedies like South Park and Veep. And yet even now, Tanner ’88 feels like its own thing: a funny and keenly observed portrait of America sluggishly awakening from its ’80s indulgences.

Angels in America (2003)

Tony Kushner’s Pulitzer- and Tony-winning play — which looks at politics, sexuality, class, gender, and race in America through the lens of the AIDS epidemic — had defied previous attempts at a screen adaptation, before Mike Nichols directed this beautifully rendered six-hour miniseries. When Angels in America’s length, scope, and subject matter made it tough to turn into a movie, HBO stepped in and gave the story the space it needed to thrive, along with a stellar cast that includes Jeffrey Wright, Meryl Streep, Emma Thompson, and — as the notorious attorney Roy Cohn — an electrifying Al Pacino. This was yet another step toward establishing the network as the place to turn for mature, powerful popular art. The network did the public a service, preserving a show that continues to resonate — especially in election years and plague years.

Related

- Every HBO Show, Ranked

- The 30 Best Movies on HBO and Max Right Now

[ad_2]

Noel Murray,Scott Tobias , 2024-04-14 18:00:00

Source link